It’s the 2003 World Series of Poker, and two players face off at the final table for $2.5 million in prize money. On one side sits Sam Farha. He wears a blazer with his collared shirt open to reveal a chain necklace. Although he has less chips, he smiles confidently.

Across the table is Chris Moneymaker. An accountant and a relative unknown, he must be too preoccupied to speculate that his appearance at the final table (along with his perfectly apt last name) will soon make the burgeoning Texas Holdem poker scene a full on craze. He wears a baseball cap and sunglasses.

In Holdem poker, five cards are placed on the table for everyone to see. Each player makes the best possible 5 card hand out of the two cards they received and the 5 cards on the table.

At this point, the dealer has dealt all the cards. Farha has the better hand, and Moneymaker knows it. Moneymaker had a chance to get a straight or a flush, but he didn’t get the last card he needed, so he has nothing. The two players have already bet hundreds of thousands of dollars on the hand. Moneymaker decides to bluff. He goes “all in” and bets everything on the hand.

Farha sits calmly, playing with his poker chips. Moneymaker wears his best poker face, keeping one hand on his chin and refusing to react. Farha even tells Moneymaker, “You must have missed your flush,” correctly stating Moneymaker’s hand and calling him out as bluffing. But Moneymaker doesn’t budge.

A maxim of poker is to play your opponent, not the cards you’re dealt. A good player scrutinizes opponents for clues: A slight wince may reveal that an opponent did not get a hoped for card. Sitting up straighter could hint that he or she intends to make a big move. At the same time, a good player wears a poker face that reveals no hint of his or her true emotions.

But is it a myth? Can a social animal like a human really perform the sophisticated double task of keeping their face a mask while reading their opponents?

This was the questions posed by Kristin Schneider of Duke and Roelie Hempel and Thomas Lynch of the University of Southampton during an investigation into how suppressing emotions impacts sensitivity to facial expressions. Their results, accepted by the American Psychological Association under the title “That ‘Poker Face’ Just Might Lose You the Game! The Impact of Expressive Suppression and Mimicry on Sensitivity to Facial Expressions of Emotion,” should give poker players of any level pause.

The researchers start their paper by noting that nonverbal cues, including emotions, are important for navigating social contexts from dinner parties to job negotiations. But emotional expression is not a one way street. We look at the facial expressions of friends and strangers to understand their emotions, but also to regulate our own. A funeral can have joyful moments as well as somber ones, so a strong feedback loop between other’s emotions and your own is important for behaving appropriately.

Researchers refer to a poker face, or any attempt to remain expressionless, as “expressive suppression.” Prior psychological research on the subject explains why it can be so hard to maintain. Holding a poker face is possible, but attempts to control the internal experience of an emotion “either fail to decrease or paradoxically increase emotion experience.” So trying to restrain your own nervousness while bluffing can only increase it, making it even more difficult not to reveal.

No one expects sincerity on the faces of their poker buddies. But as is understood in every joke about a woman asking how her jeans fit, suppressing emotions is easily detected and never appreciated. For this reason, chronic expressive suppressors – such as people suffering from depression or posttraumatic stress disorder – can easily alienate others and find it hard to befriend others.

Past research also suggests that they struggle socially because they are unable to read other people’s expressions. But it’s unclear why. Is it that hiding emotions is so mentally taxing that suppressors are too distracted to read people? That the cognitive load of putting on a poker face takes up all our attention?

On the other hand, people consistently mimic the expressions and emotions of others. Even if it’s just a picture, seeing a smile elicits a microsmile and activates parts of the brain related to happiness. Seeing a furrowed brow elicits a micro furrow and activity in the corresponding brain region. Perhaps exerting control over our emotions prevents us mimicking and thus discerning other’s emotions?

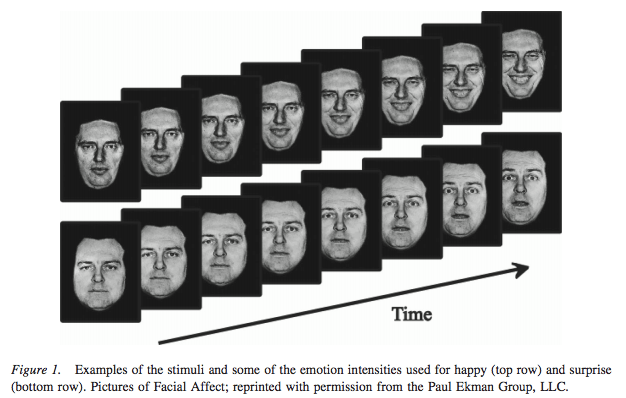

To test the effect of suppressing facial expressions, the researchers recruited university students for an experiment. The students watched computer screens that showed pictures of a face transitioning frame by frame from a neutral expression to an emotion like happiness or anger. They were also divided into 3 groups: One had instructions to keep their face expressionless, another had no instructions, and the final group was told to intentionally mimic the expression they saw on screen.

As the students watched each face, their task was to state the expression (happiness, surprise, anger, etc) as soon as they recognized it. Research assistants measured their responses for speed and for accuracy. Students who accurately recognized the emotion earlier in the transition were said to have greater “facial affect sensitivity.”

By instructing one group to intentionally mimic the expressions they saw, the researchers hoped to tease out what causes decreased facial sensitivity. Mimicking, like holding a poker face, is a task that demands attention. But mimicry is also thought to aid facial affect sensitivity. If the mimicry group was actually the fastest, then it would support the idea that we understand emotions by mimicking them.

After running the tests, the researchers found that the group suppressing their expressions were slower to recognize emotions, but the mimickers were not significantly faster than the no-instructions group:

The study therefore concludes agnostically on the question of why poker faces impair the recognition of expressions. The group intentionally mimicking the pictures were faster than the no-instructions group, but not significantly so. This made it impossible to conclude whether intentionally mimicking helped, just not enough to overcome the distraction of copying the image’s expression, or whether it is only the cognitive difficulty of holding a poker face that impairs recognition of emotions.

But the researchers did demonstrate the effect itself – at least within a lab. Someone with a poker face will not miss an opponent with a big smile on her face when she look at her cards – participants suppressing their expressions were not significantly worse at correctly stating the expression they saw on the final slide. But when it comes to identifying slight signs of emotion – the hints revealed by a careful player – someone trying to hold a poker face is more likely to miss them.

In Chris Moneymaker’s case, he no longer needed to read his opponent. He had no control over the outcome, so he was free to focus on remaining expressionless. After two grueling minutes, Sam Farha folded and conceded the hand. The ESPN announcers declared it the “bluff of the century” and Moneymaker went on to win the entire tournament in the next hand.

Poker faces are not necessarily a bad idea. As the authors point out, these findings may be most important for professions like law enforcement or medicine. Police officers interviewing a victim try to maintain a professional demeanor, devoid of expression, while seeking out information about others’ emotions. Yet this research shows the inherent difficulty of doing so. This is particularly true of a therapist’s work.

In poker, however, both players are equally handicapped by their poker faces. The meaning of a player’s behavior is also inferred from prior bets more often than from emotional slips. In Moneymaker’s case, he decided to bluff because Farha had suggested a winner take all format (rather than the 2nd place finisher receiving a $1.3 million consolation prize). He interpreted Farha’s confidence as a sign that he intended to win with a series of small, skillful bets.

But if this research is correct, poker players who think they are picking up subtle hints of emotion on their opponents’ faces might want to think about how much they’re revealing on their own.

This post was written by Alex Mayyasi. Follow him on Twitter here or Google Plus. To get occasional notifications when we write blog posts, sign up for our email list.