Paris Hilton surrounded by paparazzi. Photo credit: Jon Rawlinson

Before John F. Kennedy’s assassination in 1963, the handsome, young president had a public image as a doting father and as the man who called Americans to public service. In his private life, he was a serial adulterer. Historians have all but confirmed Kennedy’s involvement with women ranging from Marilyn Monroe to two White House interns who skinny dipped in the presidential pool and flew on Air Force One so that, as Caitlin Flanagan puts it in The Atlantic, “the president could always get laid if there was any trouble scaring up local talent.”

If a current president acted like Kennedy, reporters from every paper would seize on rumors until his presidency ended in shame. But the early 1960s were a different time; the American public remained ignorant of Kennedy’s affairs because no one reported on them. In his biography of Kennedy, Robert Dallek writes that Kennedy “remained confident that the mainstream press would not publicize his womanizing.” Even more incredible than the press’s self-imposed censorship is Dallek’s observation that when gossip columns began speculating about JFK and Marilyn, he sent a friend and former journalist to “tell the editors… that it’s just not true.” Apparently it got results.

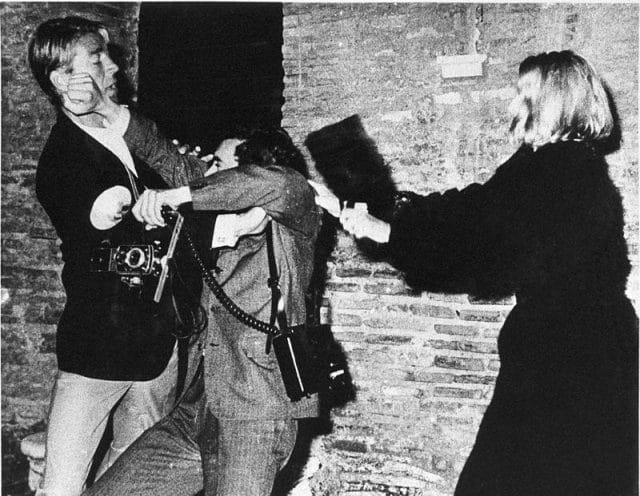

After the JFK assassination, Jackie Kennedy lived in New York. She remained in the public eye as a fashion icon and as the widow of the fallen president, but she harbored no great secrets. Nevertheless, a Bronx resident by the name of Ron Galella would not leave her alone. Galella followed Jackie Kennedy Onassis incessantly, snapping pictures of her around the city and leading the former first lady to go to court to win a (largely ineffective) restraining order against Galella.

Today famous figures endure the Galella treatment on a regular basis. Galella is the progenitor of the modern paparazzo who takes pictures of celebrities “doing things,” as he puts it, which is now so common that photographers struggle to get a good picture of Brad Pitt grabbing takeout because so many other paparazzi are crowding him to get a shot.

The proliferation of media devoted to covering famous figures, omnipresent paparazzi, and a change in the culture of how we treat celebrities — from adoring them from a distance to seeking both familiarity and the exposure of all their secrets — has led to an increase in the price of fame. Whereas Kennedy could trust the press not to expose his affairs, modern celebrities must design their lifestyle around avoiding cameras whenever they eat out. Over time, the public has come to expect a certain amount of transparency around famous people’s personal lives. We are all paparazzi now.

A Paparazzo’s Guide

Paparazzi work at the intersection of free speech and indifference to the norms of polite society. Anyone sufficiently famous is considered a “public figure” who in some ways waives the right to privacy by pursuing a public-facing career. This means paparazzi have the right to take a picture of a celebrity in public, which is why so many celebrity magazines are filled with pictures of famous people walking to their car or down the street. Some celebrities, like Jackie Onassis, have fought off persistent paparazzi by arguing that their tactics constitute harassment, and lawmakers in some areas have passed laws to prevent photographing celebrities’ children, given their status as minors. In general, however, nothing prevents paparazzi from following and photographing a celebrity like an FBI surveillance team.

At the highest levels of the cat and mouse game between paparazzi and celebrities, each side has a number of go-to tactics. The default paparazzi strategy is standing at the entrance to restaurants and clubs frequented by the rich and famous and photographing whoever turns up. Paparazzi make their own luck by befriending (and paying) waiters and bellhops to form celebrity spotting intelligence networks. In Galella’s day, paparazzi often jumped out from behind bushes or whistled to get “reaction shots”; now paparazzi flock to famous figures in such numbers that they work together, forming a “triangle” by surrounding the celebrity on three sides so that someone will get a shot no matter which direction he or she looks.

For hot celebrities, evasion goes far beyond wearing a hat and sunglasses. In The Atlantic, David Samuels writes:

Brad Pitt is a master at playing games. One of his favorite tricks is to drive onto the Warner Bros. lot and leave the photographers guessing which of the studio’s many exits he will choose for his departure.

As a result, the most lucrative photos require an incredible amount of effort to capture. At the height of Britney Spear’s notoriety, Samuels estimates that 30-45 paparazzi followed her every day. Paparazzi spend enough time waiting outside celebrities’ homes, hoping to catch a celebrity couple fighting or driving home drunk, that it has its own name: “door-stepping.” In Spears’s case, one firm “logged over 40,000 man-hours watching Britney,” which paid to the tune of $6 million worth of photos, including one of the emotionally turbulent singer shaving off her hair.

Some of the “best” images also skirt the borders of legality; Galella plucked leaves from Katharine Hepburn’s hedge and spent several days in a warehouse near Elizabeth Taylor’s yacht to get clean shots. Paparazzi agencies have already started experimenting with using drones to take photos and footage of celebrities and their real estate; powerful zooms can also nab candid celebrity photos, like when a paparazzi took a photo of Kate Middleton, the wife of Prince William, sunbathing topless from an estimated kilometer away.

Actor Mickey Hargitay and another woman get upset with famed 1960s paparazzo Rino Barillari. Photo credit: Ziogiucas via Wikimedia

To reduce the incentives for dogged paparazzi, some celebrities hawk or release highly prized photos. Angelina Jolie and Brad Pitt sold several tabloids photos of their newborn twins for $14 million (which they donated to charity). In 2000, Catherine Zeta-Jones and Michael Douglas sold their wedding photos for over $1 million. Despite the sale — and security precautions that included sweeping the hotel for video equipment, keeping the location a secret until the last minute, and hand delivering coded invitations — a freelancer still took and sold photos of the event, resulting in a lawsuit by the couple.

Many paparazzi defend their invasive occupation by saying that it benefits celebrities’ careers. There’s truth to this. Managers and publicists regularly maintain relationships with paparazzi, tipping them off to a star’s schedule to maintain their client’s celebrity by keeping them in the public eye. Of course, the absence of such relationships does not deter the photographers. For famous figures, pursuit by the paparazzi is an occupational hazard that is greatly reduced but not eliminated by living outside Los Angeles, New York, and other cities where celebrities congregate.

In an interview, British actress Sienna Miller acknowledged that it is hard to sympathize with wealthy celebrities, but refuted the claim that she benefitted from the exposure: “My career suffered massively because I had a reputation for being a very tabloid person.” Since winning a harassment case against many of England’s largest paparazzi agencies, Miller is no longer followed by photographers. She won the judge over by showing footage she took of the paparazzi as “they routinely tried to cause accidents, swore at her and backed her into dark street corners.”

Three Stages of Paparazzi

Since the coining of the term paparazzi in 1960 (Paparazzo was the name of a news photographer in the Italian film La Dolce Vita), the paparazzi industry has gone through three overlapping stages.

In the first, paparazzi were lone freelance photographers like Ron Galella. The job was both esteemed and despised. Men like Galella, who says that he considered Jackie Onassis both his favorite subject and his girlfriend, established the sleazy reputation of paparazzi. At the same time, his photos have become iconic, and a number of art museums have hosted exhibits of Galella’s photographs.

Paparazzi do still operate as freelancers, selling photographs to gossip rags and mainstream media alike, although there are now so many that it’s nearly impossible to achieve the fame of their forebearers like Galella and Rino Barillari. A Times article puts the price for an average photo at several hundred dollars, with an especially productive paparazzi earning $10,000 a month. One paparazzo, who tells Forbes that photographers usually lowball their earnings to dissuade amateurs from competing with them, says $60,000 to $100,000 is a typical annual salary for professionals. Of course most of the men — they are almost all men — are motivated by the possibility of a six or seven figure photo like Britney shaving her head or Kate Middleton sunbathing topless.

The profession has not gotten more professional. The same Times piece relates how L.A. paparazzi go by strange names “like the Fingerbreaker and Cheesecake.” Sienna Miller’s experience shows that the rhetoric of respecting celebrities is mostly fiction, and many paparazzi misogynistically refer to the practice of celebrities facilitating photos by the sexually suggestive phrase “giving it up.”

These freelancers work, however, in an environment dominated by a few paparazzi agencies that hire small armies of “shooters” or “paps.” The largest is X17, which according to Samuels in The Atlantic, pays around 70 shooters $800 to $3,000 a week and an occasional bonus. The shooters will never have a museum exhibition; most are low-income, often immigrants, who shoot with cheap cameras.

Today we’re seeing the beginning of a third stage in the paparazzi business, in which hired photographers are less necessary as smartphone cameras turn everyone, even the stars, into paparazzi. Many agencies now have online submission forms that allow anyone who bumps into someone famous and takes a picture to get paid for it. Especially for online content, many entertainment publications simply grab pictures taken of celebrities from social media, including pictures that famous people themselves post on Instagram. This is likely done illegally — whoever posts a photo on Instagram or Facebook retains the copyright — yet “stories” about Kim Kardashian’s latest activities pull from her Instagram, and mainstream press has taken from social media when an unknown individual is suddenly part of a major story.

A screenshot from the TMZ website

A couple choice lawsuits could slam the breaks on this and cede the paparazzi business back to “professionals,” and devoted paparazzi will still get most of the big scores. But devoted fans can play the stalking game very well. In 2013, the New York Times profiled Stalker Sarah, a teenager who has taken pictures with over 6,000 celebrities. Sarah politely asks to take a picture with singers and actors, and she refuses to sell her photos despite often finding celebrities in compromising situations. Other fans doing the same may not be as loyal, and free or cheap photos taken by fans will be increasingly alluring to papers. As The Economist reports, the way that scandalous pictures can rocket around the Internet means that publications no longer find even exclusive photos nearly as valuable. One paparazzo informed the venerable paper, “The Internet has ruined it for everybody.”

How We See the Stars

In his 2005 book The Stars, Edgar Morin of the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique writes that through World War II, celebrities “live[d] at a distance, far beyond all mortals.” In the postwar period, however, stars became more approachable and familiar. The paparazzi played a key role in this, but they were just one part of a larger cultural shift that brought the gods down from Olympus and made famous people “just like us.”

In a long profile of entertainment news juggernaut TMZ, Anne Helen Petersen characterizes the press’s coverage of the entertainment industry up until the 1950s as “blow job news.” When the government threatened censorship on Hollywood following a series of scandals in the 1920s, movie studios and the press engaged “in a symbiotic relationship in which one would provide a constant stream of material about the stars and advertising dollars in exchange for the implicit understanding that the magazines would not print anything that contradicted the studio line of stars as moral exemplars.” All mention of celebrities as real people, especially their misdeeds, were subsumed under the squeaky clean marketing lines of 1950s America.

Petersen cites Confidential, a 1950s magazine that broke this truce and published scandalous accounts of Frank Sinatra’s sex life and Liberace’s homosexuality, as the precursor of today’s gossip magazines. Not coincidentally, it thrived at the same time that the first famous paparazzi like Galella and Barillari started stalking celebrity prey.

Confidential disrupted the management of celebrities’ image (TMZ, which launched in 2005, avoids all “managed” events like red carpets and weddings); later magazines would do the same while feteshizing the banality of celebrity existence. While working as an editor at Us Weekly, Bonnie Fuller tells The Atlantic:

“Every day, we’d look at tons of pictures that came in and lay them all out on a conference table. And what was interesting to me was to look at celebrities going to the dry cleaners and pumping gas. I loved looking at these pictures of celebrities who were just like us.”

Fuller helped invent the practice of publishing the most mundane celebrity photos along with short captions about what the famous people in each are up to. It was a boon to paparazzi, who suddenly found a profitable market for a picture of Hilary Swank stuffing a hot dog in her mouth, and to gossip writers who no longer needed to sniff out a scandal or hunt down rumors. (Or make one up.)

Part of the appeal for writers was the excitement of seeing stars act “just like us,” but especially at TMZ, appeal lay in reveling at the sight of celebrities’ banal existence, smirking as celebrities stumble out of clubs or look ugly without their wardrobe assistants. The press’s and the readers’ philosophy seemed to be: we’ll make up the market that allows you to profit off your fame, but in return we demand a pound of flesh.

With the advent of blogs, comments sections, and social media, the dissection of famous people’s lives became a pastime accessible to everyone, allowing people to move their gossip about celebrities from private conversations to the public sphere. Even if we’re not taking the pictures, we’re all paparazzi. Bashing and praising celebrities is nothing new, but now the criticism or praise is more of a flood. It is a novel feature of the media environment that actress Anne Hathaway is defined much more by the public’s hatred of her than by the Oscar she won for playing Fantine in Les Miserables. Every famous figure risks being pulled into a maelstrom of public opinion that alternatively idolizes them, seeks from them the familiarity of a friend, and revels in seeing them humiliated.

Larger Than L.A.

Given that the paparazzi treatment mostly applies to a small group of singers and actors in Los Angeles and New York who make large amounts of money off their celebrity, it’s easy to shrug at what seems to be a fair trade-off: wealth and fame for these annoyances. But there is a good reason to care.

Namely, the paparazzi treatment — particularly the aspect of being trashed in a flood of media — is relevant outside entertainment in fields like politics. Criticism is not new for politicians; their job is essentially war by other means, so they’ve always been the target of ire from about half the country. But the scope of the criticism has heightened. In Rolling Stone, a recent article from a former White House spokesperson details how ever increasing amounts of media — the 24-hour news cycle, blogs, social media — means that it’s increasingly difficult for politicians to control a narrative and more and more common for media to turn every small bit of news into a setback or a scandal.

The very personal nature of the criticism also appears to be a development. Writing in The New York Times, David Brooks notes that through the 1950s, journalists kept mum on personal details — whether that meant not considering Kennedy’s womanizing a story or not publishing a private outburst. Beginning in the 1960s, however, just as entertainment news pierced the veil around celebrities’ lives, political reporting put “the soap opera” of politicians’ infighting, relationships, and private language front and center. In the 2012 race for a Massachusetts Senate seat, candidate Elizabeth Warren quipped that when working her way through college as a waitress, she “kept her clothes on.” Her opponent Scott Brown, who modelled underwear to help pay for college, responded, “Thank god.” The exchange, which may have once been forgotten as an impolite lapse in judgment by both candidates, became headline news, discussed for days.

Even in stuffy politics, we see the same participatory news in which the public not only casts judgment on the actions of people in the news, but criticizes, idolizes, and seeks familiarity with them as people. A million blog posts and articles have argued over whether Sarah Palin is a vain black hole of our attention or a patriotic fountain of common sense. Joe Biden may be best known — even from the media about him — as an object of women’s affections and an Internet meme. And between book deals and speaking appearances, fame can be just as financially rewarding to politicians and other figures as it is to actors, singers, and comedians.

The way in which Americans lay famous people’s lives on a public dissection table holds both promise and peril. The media circus that surrounded Bill Clinton’s sexual relations with a White House intern was probably preferable to the media’s self-imposed censorship around Kennedy’s serial adultery. And in her article, Peterson concedes that although TMZ makes a living off sleazy and often sexist coverage of celebrities’ lives, it too has an investigatory zeal that most recently brought attention to the racist views of LA Clippers owner Donald Sterling.

The downside is the effect all the scrutiny and paparazzi stalking could have on who joins the ranks of the influential and famous. As actress Sienna Miller pointed out while describing her treatment by paparazzi, it is hard to feel for celebrities with their “first-class tickets and Burberry bags.” In the United States, economic gains have increasingly flowed to the upper echelons of the income bracket, which very much includes famous people who get the paparazzi treatment.

But for better or worse, those famous people serve as role models and hold enormous influence — regardless of whether the celebrity in question is Lindsay Lohan or Ellen Degeneres, Sarah Palin or Hillary Clinton. The question we may all want to ask ourselves is this: Do we really want the ranks of famous, influential people to be filled exclusively by individuals who are willing to put up with an increasing amount of negative press, harassment, and intrusion into their personal lives for the sake of huge piles of money?

This post was written by Alex Mayyasi. Follow him on Twitter here or Google Plus. To get occasional notifications when we write blog posts, sign up for our email list.