“The average expert’s forecasts were revealed to be only slightly more accurate than random guessing—or, to put more harshly, only a bit better than the proverbial dart-throwing chimpanzee. And the average expert performed slightly worse than a still more mindless competition: simple extrapolation algorithms that automatically predicted more of the same.”

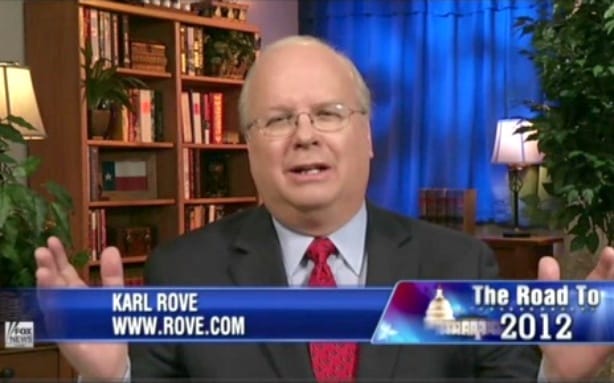

During the presidential election, statistician Nate Silver consistently predicted on his FiveThirtyEight blog (hosted by the New York Times) that the odds of Mitt Romney winning the presidency were slim. Leading conservative political experts like Karl Rove and Newt Gingrich called his claims ridiculous. Silver kept the faith in his poll numbers and models; the pundits trusted their “years of experience.”

In the end, Silver (whose background was the moneyball world of applying statistics to baseball) embarrassed the pundits by accurately predicting which states would be won by each candidate. But you wouldn’t know it by looking at the careers of the experts. News channels never stopped welcoming Newt Gingrich and his ilk as experts, while Karl Rove continues to accept healthy paychecks as an expert consultant for political campaigns around the world. The consequences of their nationally televised embarrassment were exactly nil.

It is this lack of accountability when it comes to making predictions that fascinates Philip Tetlock, a professor at the University of Pennsylvania. His interest in expert judgment began after the end of the Cold War. Despite both conservatives and liberals failing to predict how the Soviet Union would end, he saw both sides fit the emerging developments to their original ideas – the same ideas that had just failed.

In 2005, he published Expert Political Judgment: How Good Is It? How Can We Know? on this subject. When it came to evaluating the judgment of television pundits, however, he realized that he was missing the point of punditry:

“One of the reactions to my work on expert political judgment was that it was politically naïve; I was assuming that political analysts were in the business of making accurate predictions, whereas they’re really in a different line of business altogether. They’re in the business of flattering the prejudices of their base audience and they’re in the business of entertaining their base audience and accuracy is a side constraint.”

The key for these pundits, he notes in a recent article on Edge, is to use “vague verbiage to disguise their prediction.” In particular, constant use of the word “could” gives pundits plausible deniability when their predictions go south.

Pundits may not be in the game of prediction. However, experts making predictions with the intention of being accurate, from Economist writers to CIA analysts, do not fare much better when their forecasts are evaluated. Tetlock began tracking the predictions made by political analysts and came to 3 conclusions:

1) Political analysts can rarely do better than chance when forecasting more than one year into the future

2) Political analysts are overconfident – they’re right 60% to 70% of the time when they say they’re 80% or 90% confident

3) Political analysts don’t change their minds when they’re wrong

With these dismal conclusion, Tetlock and his colleagues began asking how to improve forecasting abilities. Silver could predict the odds of an Obama victory, Tetlock notes, because forecasting a presidential election is similar to knowing the odds of a poker game. The election is a repeat event with clear rules and a wealth of data that make modeling possible.

But what about predicting the odds that the Eurozone will collapse? Or the odds that Iran will have a nuclear weapon within the next 30 years? These are not repeat events. There is less relevant data. As a result, experts have a terrible track record of predicting these type of events. Is that because they are doing a poor job of it? Or is it impossible? What is the “optimal forecasting frontier?”

To answer these questions, Tetlock has taken the approach of enlisting anyone in the business of making predictions – journalists, political analysts, intelligence leaders – to join forecasting tournaments. Each expert states the odds of a series of easily testable propositions (i.e. “will Greece leave the Eurozone by May 2013?”) They then receive an accuracy score based on how highly they rated the probability of events that do come to pass and advance in the tournament based on that score.

In this way, forecasting tournaments bring accountability to the prediction process. They set a baseline, compare experts’ predictions to chance, and demonstrate whether their accuracy can be improved. One insight of the tournaments, which you can read more about here, is that confidence and grand theories are bad. Forecasters who expressed confidence in their clairvoyance and widely applied the theories they believed in did poorly. Those who remained skeptical of their own predictions and the explanatory powers of overarching frameworks did at least mildly better.

While not a key part of Tetlock’s work, a fascinating aspect is the question of why efforts to measure and improve our forecasting abilities are so rare. After all, it’s not like we are unaware that expert opinion fails frequently. As Dr. Tetlock points out, year after year The Economist publishes a preview of the year to come. And every year they fail to predict any of the biggest developments of the coming year. Similarly, American intelligence agencies whiffed on predicting the 9/11 attacks, the presence of weapons of mass destruction in 2003 Iraq, the Arab Spring, and the attacks on the Libyan consulate in 2012. The result was hearings and token policy changes. Organizations spend staggering amounts of time and money trying to predict the future, but no time or money measuring their accuracy or improving on their ability to do it.

Dr. Tetlock argues that the astounding lack of accountability or review over prediction exercises across business, government, and civil society is because the ability to predict through expert judgment (or at least to seemingly do so) is a status issue:

“The long and the short of the story is that it’s very hard for professionals and executives to maintain their status if they can’t maintain a certain mystique about their judgment. If they lose that mystique about their judgment, that’s profoundly threatening.”

Most of the volunteers participating in the research team’s “forecasting tournaments” are young and not high up in their organizations. That’s because no supposed expert is willing to chance being found a fraud. Dr. Tetlock refers to the tournaments as “radically meritocratic” and points out that “If Tom Friedman’s subjective probability estimate for how things are going in the Middle East is less accurate than those of the graduate student at Berkeley, the forecasting tournament just cranks through the numbers and that’s what you discover.” He believes that the experts’ egos, and the fact that a lack of accountability is key to their status, prevents accountability or progress on the prediction front.

Another explanation for our persistent failure to deal with our failed predictions comes from the experience of economist Kenneth Arrow during World War II. As Tetlock relates, Arrow became alarmed that his superiors in the army were making plans based on month-long weather forecasts which were no more accurate than random guesses. When he voiced this opinion, he was told, “The Commanding General is well aware the forecasts are no good. However, he needs them for planning purposes.”

In other words, our predictions may be crap, but we don’t have a better alternative. We need to have some idea of what the future holds in order to make intelligent plans. Admitting to our inability to predict the future would be conceding to constantly flying blind. How paralyzed would foreign policy or corporate strategy become if we admitted that the future is unknowable? So, we put on our blinders and double down on inaccurate predictions because we need something to make future plans by.

The embarrassment of certain pundits at Nate Silver’s hands shows that the media is ignoring opportunities for more accurate, data-driven analysis. However, in the majority of cases, the suckiness of pundits may come from the fact that we are asking them questions we know to be impossible, yet still demanding answers.

This post was written by Alex Mayyasi. Follow him on Twitter here or Google Plus. To get occasional notifications when we write blog posts, sign up for our email list.