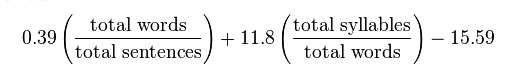

Recently, the Priceonomics team released a tool that measures the reading level of any text. To achieve this, we use five of the most commonly used reading indexes — the Automated Readability Index, the Coleman-Liau Index, the Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level Index, the Gunning-Fog Index, and the SMOG Index — all of which are based on some type of variant of the following formula:

Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level formula

In simple terms, writing with longer sentences and bigger words yields a higher score (grade level) than simplistic writing. Thomas Paine’s Common Sense, for instance, clocks a Flesch-Kincaid grade level of 12.0, while Dr. Suess’s Green Eggs and Ham registers a -1.3.

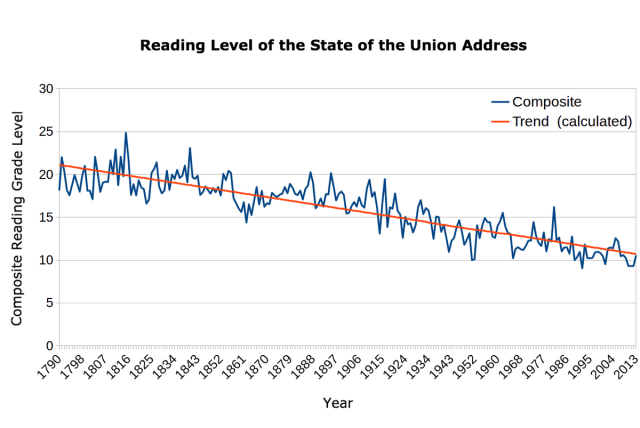

In honor of Presidents’ Day, we decided to analyze every State of the Union Address ever spoken and/or written. The results: over time, the reading level of the speeches has substantially declined.

A Brief History of the State of the Union Address

Long before it became known as the “State of the Union” in 1946, the President’s most anticipated speech was known simply as the “Annual Message.”

On January 8, 1790, George Washington delivered the first Annual Message before Congress. At just 1,089 words, it was short and sweet, but it set a precedent in place: from then on, every subsequent President would prepare a similar annual message, propounding on the state of affairs in America.

Eleven years later, in 1801, then-President Thomas Jefferson declared that the speech be written, rather than be delivered in-person. Throughout the century, the annual message was a “lengthy administrative report on the various departments of the executive branch and a budget and economic message.” As such, its lexicon was more complex, and was geared toward Congress and politicians, rather than the general public.

Generally, things remained this way for the next century, until Woodrow Wilson decided to recite his address personally in 1913. From that point on, the vast majority of addresses were delivered orally — and the nature of the speech shifted more toward accessibility.

Technological changes throughout the ensuing years allowed the President to reach more people with his message:

1923: First annual message radio broadcast (Calvin Coolidge)

1947: First State of the Union television broadcast (Harry Truman)

2002: First State of the Union webcast on Internet (George Bush)

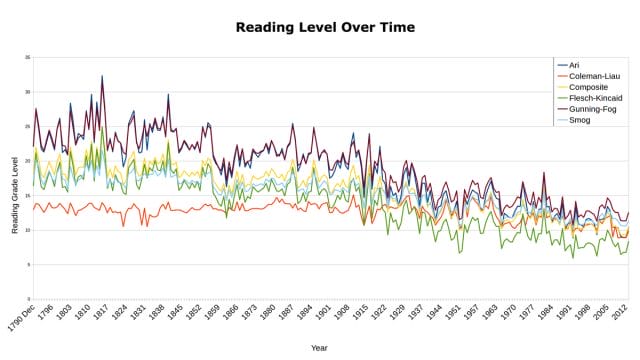

These factors, in part, have contributed to the “simplification” of the State of the Union Address’ language over time:

Note: Ari, Coleman-Liau, Flesch-Kincaid, Gunning-Fog, and Smog are all commonly used reading level indexes, and “composite” is the average score of all tests; data via Priceonomics Analysis Engine

A Presidential Analysis

The extent to which Presidents have been involved in their own speech writing has widely varied — though every one of them has enlisted help to some degree. Woodrow Wilson “mobilized literally hundreds of scholars and experts” in preparing his State of the Union Addresses, while others, like Teddy Roosevelt, preferred to write most of it alone. It wasn’t until the mid-1930s, under President Roosevelt’s administration, that official speechwriters were integrated; since then, they have become a mainstay.

Since 1790, 43 U.S. Presidents have delivered a total of 226 State of the Union Addresses (or Annual Messages). Some Presidents (Zachary Taylor) delivered as few as 1; others (James Madison, Theodore Roosevelt, Ulysses Grant) delivered as many as 8.

We took all of these speeches and ran them through our five reading level indexes, and calculated the composite score of each. Then, we averaged the composite scores of each President’s speeches, and ranked them from highest grade level, to lowest:

James Madison, the United States’ President from 1809 to 1817, is the clear-cut “winner,” with speeches averaging a grade-level of 21.5. To understand why his speeches rank so highly, let’s break down an excerpt from an Annual Message speech he gave in 1810:

“The act of the last session of Congress concerning the commercial intercourse between the United States and Great Britain and France and their dependencies having invited in a new form a termination of their edicts against our neutral commerce, copies of the act were immediately forwarded to our ministers at London and Paris, with a view that its object might be within the early attention of the French and British Governments.”

This whopper of a sentence — 71 words, 9 of which are 10 characters or longer — is indicative of Madison’s speeches in general: complex, wordy, and Thesaurus-worthy.

By all historic accounts, Madison was lauded both for his writing skills, and eloquence. Despite being “painfully shy [and] physically frail,” his words commanded the attention of Congress and major political influencers. “If the art of persuasion includes persuasion by convincing,” once wrote Chief Justice John Marshall, “Mr. Madison was the most eloquent man I ever heard.” Before crafting his own speeches, Madison advised and heavily edited the speeches of George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, and John Adams — all three of whom are ranked in the top 10 here.

President Obama’s speeches, which rank lowest on the list at a grade level of 9.8, are of an entirely different nature. Take, for example, this excerpt from his recent 2015 Address:

“But tonight, we turn the page. Tonight, after a breakthrough year for America, our economy is growing and creating jobs at the fastest pace since 1999. Our unemployment rate is now lower than it was before the financial crisis. More of our kids are graduating than ever before. More of our people are insured than ever before. And we are as free from the grip of foreign oil as we’ve been in almost thirty years.”

This section is roughly the same length as the one we pulled from Madison’s speech (340 characters), yet contains six sentences, as opposed to Madison’s one. Likewise, Obama uses only three words 10 characters or more in length.

Comparing and contrasting these two Presidents exposes a larger motif: United States Presidents have made their speeches simpler over time.

All of this data is not to imply that simpler speeches are inferior. For instance, John F. Kennedy and Franklin D. Roosevelt, who respectively rank 30th and 31st on our reading level list, are both considered to be among the best speakers in history by Presidential scholars.

Still, if this downward trend continues at the same rate, State of the Union speeches will be targeted towards kindergarteners (reading level 0) by the year 2243.

![]()

This post was written by Zachary Crockett; you can follow him on Twitter here. Visualizations and data crawling by Elad Yarom

To get occasional notifications when we write blog posts, please sign up for our email list.