“When you’re born, you get a ticket to the freak show. When you’re born in America, you get a front row seat.”

![]()

In 19th century America, gawking at people who were born with deformities was not only socially acceptable — it was considered family entertainment.

P.T. Barnum made millions by capitalizing on this. His “freakshows” brought together an amalgam of people considered to be curiosities — bearded ladies, tattooed men, the severely disfigured, and the abnormally short and tall — many of whom were unwillingly forced into the industry as young children.

Barnum hyperbolized (or altogether falsified) the origins of these performers, which made them out to be beasts, rare “specimens,” and cretans. When he met criticism for “perpetuating hoaxes”, he countered that he was only on a mission to sprinkle society with a little magic: “I don’t believe in duping the public,” he wrote to a publisher in 1860. “But I believe in first attracting and then pleasing them.”

He accomplished both of these things through exploitation — yet many of his performers were paid handsome sums, some earning as much as today’s sports stars. The rise and fall of the “freakshow” business is a fascinating economic story, but also a morality tale.

P.T. Barnum and the Rise of the Freakshow

The “freak show,” or “sideshow,” rose to prominence in 16th century England. For centuries, cultures around the world had interpreted severe physical deformities as bad omens or evidence that evil spirits were present; by the late 1500s, these stigmas had translated into public curiosity.

Businessmen scouted people with abnormalities, swooped them up, and shuttled them throughout Europe, charging small fees for viewings. One of the earliest recorded “freaks” of this era was Lazarus Colloredo, an “otherwise strapping” Italian whose brother, Joannes, protruded, upside down, from his chest.

The conjoined twins “both fascinated and horrified the general public,” and the duo even made an appearance before King Charles I in the early 1640s. Castigated from society, people like Lazarus Eager capitalized on their unique conditions to make a little cash — even if it meant being made into a public spectacle. But until the 19th century, freak shows catered to relatively small crowds and didn’t yield particularly healthy profits for showmen or performers.

Meanwhile, in Connecticut, P.T. Barnum had already established himself as a brilliant marketer. By 19, as a storekeeper and early lottery-ticket seller, he’d already married deception and showmanship, and was making nearly $500 per week in profit ($10,700 in current dollars).

But when the U.S. governemnt passed an anti-lottery law, Barnum found himself out of work and moved to New York City. In 1835, inspired by stories he’d heard from England, he purchased a blind, paralyzed slave woman, fabricated a sensational story (that she was 160 years old and had been George Washington’s nurse), and charged viewers to see her in-person.

A year later, the woman passed away and a death report confirmed that she was only 80 years old — but Barnum’s viewers didn’t seem to care: they had been captivated by his storytelling and his deceptions had become “irrefutable truths.” Barnum had purchased the slave for $1,000, and made nearly that amount every week from his “investment.”

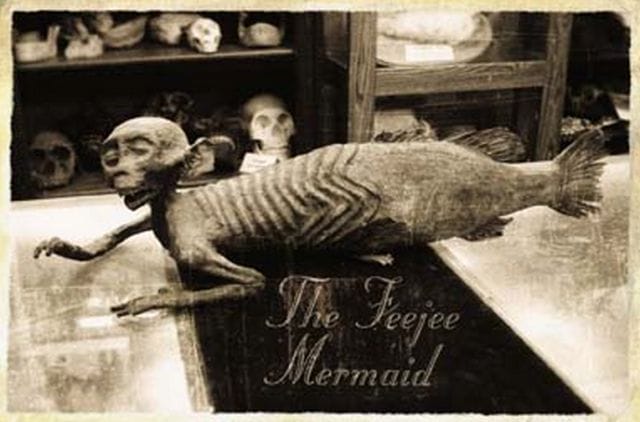

Barnum also mastered the art of colorful trickery. His first major hoax, in 1842, was the “Feejee mermaid” — a “creature with the head of a monkey and the tail of a fish.” The specimen — really the torso and head of a juvenile monkey sewn to the back half of a fish — was originally sold to an Englishman by Japanese sailors in 1822, for $6,000 ($103,500 today). After being displayed for some time in London, it found its way to New York, where Barnum negotiated to lease it for $12.50 per week.

Barnum embarked on a ferocious campaign to convince his crowds that the creature was real, feigning newspaper articles and even weaseling his way into the American Museum of Natural History. He fabricated a story about the mermaid’s discovery and distributed over 10,000 pamphlets. In a matter of weeks, he had the public’s attention.

Barnum purchased the American Museum on Broadway in New York and, throughout the 1840s, introduced a “rotating roster of freaks: albinos, midgets, giants, exotic animals” and anyone else who piqued the curiosities of the public. To advertise the space, he hired the most unskilled musicians he could find and had them play on the building’s balcony, in the hopes that this “terrible noise” would attract customers.

Under his leadership, the American freakshow became a booming business — both highly profitable and degrading for its performers.

Charles Stratton: “General Tom Thumb”

Following the success of his Feejee Mermaid, Barnum set out to find extraordinary humans who he could partner with (and capitalize on). He’d heard of a distant cousin, Charles Stratton, who had an incredible abnormality, so he went to investigate.

Stratton had been born to average-sized parents, and he developed at a normal rate until he was six months old, at which point he measured 25 inches tall and weighed 15 pounds. By age five, he hadn’t grown an inch. Barnum partnered with the boy’s father, taught the child to sing, dance, and impersonate famous figures (Cupid, Napoleon Bonaparte), and, in 1844, took him on his first tour around America.

Barnum “re-branded” Stratton as “General Tom Thumb” — “The smallest person who ever walked alone” — and told onlookers that the five year old was actually eleven. After incredible success, the two embarked to Europe, where Queen Victoria became enamored with the act; Stratton was mobbed by crowds wherever he went and achieved international stardom.

By the late 1860s, Barnum made Stratton a well-to-do man. For the better part of fifteen years, he was paid upwards of $150 per week ($4,100 today) for his performances, and, upon retiring, lived in New York’s “most fashionable neighborhood,” owned a steam yacht, and wore only the finest clothes.

Barnum was equally smitten with his new partnership: the European tour paid him so handsomely that he nearly purchased William Shakespeare’s birth home. His earnings extended well into the hundreds of thousands — money he reinvested in his business, and used to purchase his first large museum. He re-named it “Barnum’s Museum,” and by 1846, it was drawing 400,000 visitors a year.

William Henry Johnson: “Zip the Pinhead”

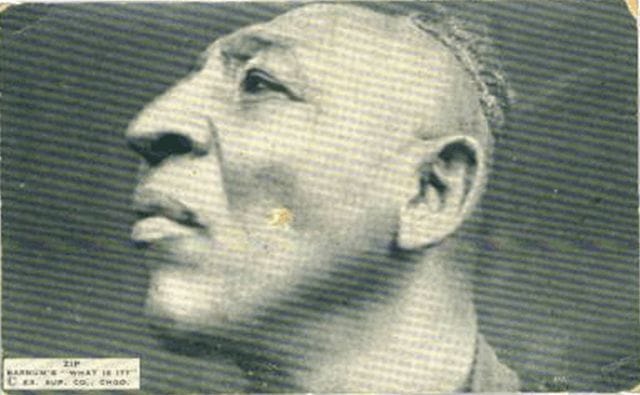

William Henry Johnson was born to impoverished, newly-freed slaves in New Jersey, in 1842. While he possessed a very subtle physical deformity (his head was slightly microcephalic, or cone-shaped), a local showman capitalized on and exaggerated it. Johnson began performing in sideshows in the mid-1850s.

In 1860, P.T. Barnum recruited him, and transformed him into “Zip,” a “different race of human found during a gorilla trekking expedition near the Gambia River in western Africa.” His head was shaved, save for a small tuft on top, and he was dressed in a head-to-toe suit of fur. Darwin had recently published his Origin of the Species, and Zip was promoted as a “missing link” — a beacon of evolutionary proof.

Barnum displayed Zip in a cage and ordered that he must only grunt; he was paid “one dollar a day” to keep quiet and stay in character. He also had Zip play a violin — so badly that he was often paid to stop by spectators.

He quickly became a star in Barnum’s rotation of “freaks,” garnering attention from the likes of author Charles Dickens and other celebrities. For his efforts, Zip was rewarded handsomely: Barnum paid him $100 per performance (of which he often had 10 per week) and purchased him a lavish home in Connecticut.

Zip was known not just for his curious origins, but for his upbeat, positive demeanor; as one spectator wrote, “he amuses the crowd and the crowd amuses him.” His showmanship extended far beyond Barnum’s eventual death, and he performed into his late eighties. He was also a masterful marketer: during 1925’s Scopes Trial, he offered himself as living proof of evolution, generating a massive amount of publicity.

Though he played a fool for the duration of his life, and was exploited, Zip was frugal and retired a millionaire. On his deathbed he reportedly told his sister, “Well, we fooled ‘em for a long time,” implying that, for decades, he’d been conning not only his audiences but sideshow operators into believing that he was mentally incapacitated.

Chang and Eng Bunker: “The Siamese Twins”

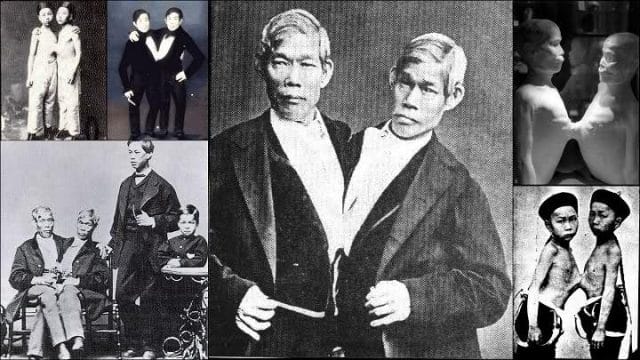

Born in 1811 in a small Siamese fishing village, Chang and Eng were conjoined twins, connected by a four-inch ligament at the chest. In the late 1820s, a British merchant established a contract with the twins and exhibited them around Europe and America for three years. Subsequently, the two split from the showman, started their own American sideshow, and gained great fame. The term “Siamese twins” was created by a doctor who witnessed the two perform.

By 1838, at age 29, they retired with $60,000 ($1.3 million today), and settled in North Carolina, where they bought a 100-acre farm and operated a plantation. After adopting “Bunker” as an “American” last name, they became naturalized U.S. citizens and met a pair of sisters, who they wed. They constructed two separate houses on their property and traded off three-day time slots in which each could spend time with his wife. Combined, the two fathered 21 children.

After running out of money in 1850, they reinstated their career as sideshow performers and signed a contract to tour with P.T. Barnum. For the next twenty years, they intermittently performed, and they died four hours apart in 1879, leaving a great fortune to their wives.

Captain Costentenus: “The Tattooed Man”

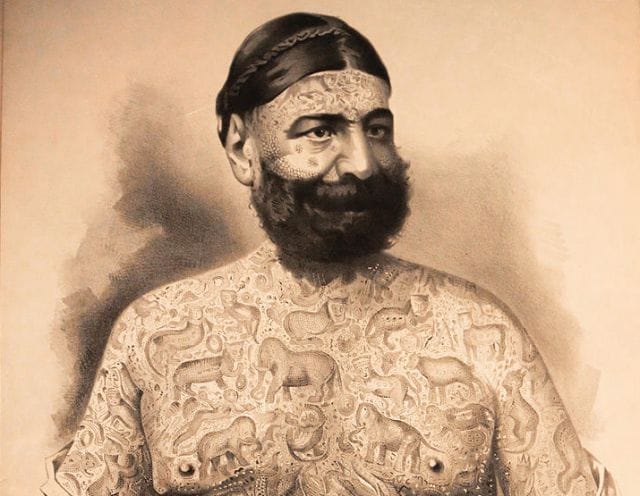

George Contentenus, America’s “first tattooed side act,” was so committed to his stage story that little is known today about his actual origins. Born in 1836, he claimed to be a Greek-Albanian prince raised in a Turkish harem.

His 338 tattoos covered nearly every inch of his body (save for his nose and the soles of his feet), were incredibly ornate, and depicted Burmese-specific species, and symbols from Eastern Mythology: snakes, elephants, storks, gazelles, dragons, plants, and flowers of all sorts intermingled on his skin.

According to Contentenus’s tale, he’d been on a military expedition in Burma when he and three others were captured by “savage natives” and offered a choice: they could either be cut into pieces from toe to head, or receive full-body tattoos and be liberated — should they survive the excruciating process. The soldiers chose the latter option, a process which took three months and killed Contentenus’s accomplices.

To convince the world that his story was true, he even went so far as to publish a 23-page book in 1881, documenting every detail of his alleged experience. It wasn’t until much later in his career that Contentenus admitted he had feigned this tale in the hopes of attaining fame and fortune. And that he did.

In the 1870s, he partnered with P.T. Barnum and became the American Museum’s highest grossing act, taking home more than $1,000 per week (an impressive $37,000 per week today). An 1878 clipping from the New York Times elaborated on his wealth:

“He wears very handsome diamond rings and other jewelry, valued altogether at about $3,000 [$71,500 in 2014 dollars] and usually goes armed to protect himself from persons who might attempt to rob him.”

“Half the people who visited [Captain Costentenus,] this last specimen of Grecian art, looked as if they would be quite willing to go through the process of having their skins embroidered, if thereby they could insure a comfortable living without labor.”

Upon his death, Costentenus donated half of his fortune to the Greek Church, and the other half to fellow freak show performers who were less fortunate.

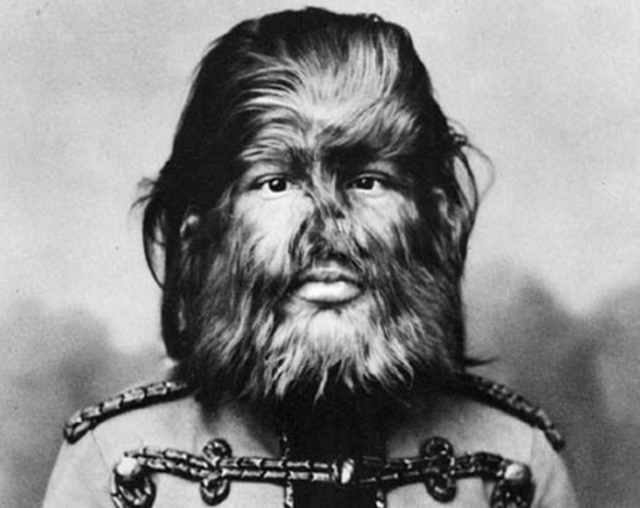

Fedor Jeftichew: “The Dog-Faced Boy”

Born with a hair-covered face in 1873, Fedor was destined to follow in his father’s footsteps. Adrian Jeftichew, known throughout Europe as “The Siberian Dog-Man,” was highly superstitious and believed that both he and Fedor were on the receiving end of divine punishment.

Following his father’s early death, the 16-year old Fedor became a ward of the Russian government. By this time, he was “covered with long, silky, fur-like hair that grew thickest on his face.” While the public perceived him to be animal-like and savage, he was contrarily inquisitive, soft spoken, and shy.

Fedor was adopted by a cold-hearted showman, brought to England, and advertised as “the boy who was raised by wolves in Siberian wilderness.” The ever-enterprising P.T. Barnum saw the act, purchased the boy’s contract, and transitioned him to the United States in 1884. But, as with any of his performers, Barnum needed to embellish Fedor’s story.

The child became “Jo-Jo The Dog-Faced Boy,” and played the stereotype of the Victorian naturalist’s approximation of a prehistoric man: he’d been found in a cave deep in the forests of central Russia, feeding on berries and hunting with a rudimentary club; after enduring a bloody battle to capture the “beast,” hunters taught him to walk upright, wear clothes, and speak like a dignified human.

Barnum dressed Fedor in a Russian cavalry uniform, and had him play up his savage nature, “barking, growling, and baring his teeth” at onlookers. Throughout the 1880s, Fedor was among the highest paid performers in the business, netting $500 per week ($13,000 today). By the time of his retirement, his saving totalled nearly $300,000 ($7.6 million).

Death of the Freakshow

Photo: Old Circus

By the 1890s, freakshows began to wane in popularity; by 1950, they had nearly vanished.

For one, curiosity and mystery were quelled by advances in medicine: so-called “freaks” were now diagnosed with real, scientifically-explained diagnoses. The shows lost their luster as physical and medical conditions were no longer touted as miraculous and the fanciful stories told by showmen were increasingly discredited by hard science. As spectators became more aware of the grave nature of the performers’ conditions, wonder was replaced by pity.

Movies and television, both of which rose to prominence in the early 20th century, offered other forms of entertainment and quenched society’s demand for oddities. People could see wild and astonishing things from the comfort of a theatre or home (by the 1920s), and were less inclined to spend money on live shows. Media also made realities more accessible, further discrediting the stories showmen told: for instance, in a film, audience members could see that the people of Borneo weren’t actually as savage as advertised by P.T. Barnum.

But the true death chime of the freakshow was the rise of disability rights. Simply put, taking utter delight in others’ physical misfortune was finally frowned upon.

The Moral Debate

Even at their peak, these shows had been vehemently critiqued as exploitative and demeaning. In 1861, British historian Henry Mayhew wrote a study in which he dismissed them as “nothing more than human degradation:”

“Instead of being a means for illustrating a moral precept, [freakshows] turned into a platform to teach the cruelest debauchery…The men who preside over these infamous places know too well the failings of their audience.”

Undoubtedly, most early sideshow performers were taken advantage of, manipulated, and pushed into the industry unwillingly. Only one of the performers we’ve profiled above, Captain Costentenus, entered the trade out of his own volition (consequently, he also made himself an oddity, rather than being born one).

In the 1950s, Carol Grant, a 16 year-old with a deformity, was highly offended after attending a sideshow, and sent a letter to North Carolina’s Agricultural commissioner. “Handicapped people are seeking more in life than being stared at in a sideshow,” she wrote. The letter garnered national attention, and raised a debate: should performers have the option of appearing in these shows, should they choose to do so?

Harvey Boswell, a sideshow operator and paraplegic, responded to Grant:

“I’m stared at but it doesn’t bother me. Nor does it bother the freaks when they are stared at on their way to the bank to deposit the $100, $150, $200, and even $500 per week that some of the more sensational human oddities receive for their showing in the sideshows.”

Long-time showman Bobby Reynolds also pitched in his two cents:

“If you’re a mutation of sorts, the biggest thrill you get is opening the mailbox and getting a check from the government. Or you get put in an institution. People say ‘Oh, you took advantage of those people!’ We didn’t take advantage of those people. They were stars! They were somebody. They enjoyed themselves.”

Nonetheless, by the mid-20th century, remaining performers migrated into traveling carnivals or museums, making only a fraction of what they made a few decades prior. Many who’d relied on sideshows to make a handsome living died in destitution, with little to no disability support.

Modern Incarnations

Photo: Lizardman

While freak shows were ousted for their questionable morals, they exist today — just not in the traditional sense.

Television network TLC, for instance, has proved that curiosity still sells. Just as P.T. Barnum exploited “Fat Boy” Ulack Eckert, TLC’s “My 600 Pound Life” exploits the sensational aspects of America’s morbidly obese. The network’s “Little People, Big World” light-heartedly portrays the struggles of a dwarf couple, as Barnum did with Tom Thumb. “The Man With Half a Body,” and “I Am the Elephant Man” each prey on the same prying eyes that funded freak shows throughout the 1800s. And, like their predecessors, these modern-day “stars” are paid for their exploitation — up to $8,000 per episode.

There are also those like Eric Sprague, who’s transformed himself into “Lizardman.” With head-to-toe green scale tattoos, a split tongue, and filed teeth — all products of personal volition — he brands himself as a “professional freak.” Just in case there’s any doubt as to whether or not this is true, “FREAK” is prominently inked across his chest. Sprague is part of a body modification subculture that explicitly seeks “freak stardom.”

But for the majority of the 19th century’s “freaks,” notoriety wasn’t a choice. They grew to accept their lifestyles and appreciate wealth and fame, but paid for it in other ways. Frank Lentini, a three-legged man who was once dubbed “King of the Freaks,” confirmed this in a newspaper interview at the turn of the century.

“My limb does not bother me,” he wrote, “as much as the curious, critical gaze.”

This post was written by Zachary Crockett. Follow him on Twitter here, or Google Plus here.