Imagine this: it’s 3:30 in the morning, and you’re deep in some pillowy dreamscape. All is calm; all is serene. Then, a piercing alarm whiplashes your senses: you’re awake now, scrambling in the darkness with ten equally frazzled men. In a flurry, boots are pulled on, helmets are snatched off shelves, and you’re flying down a 20-foot pole with the rapidity and dexterity of a howler monkey.

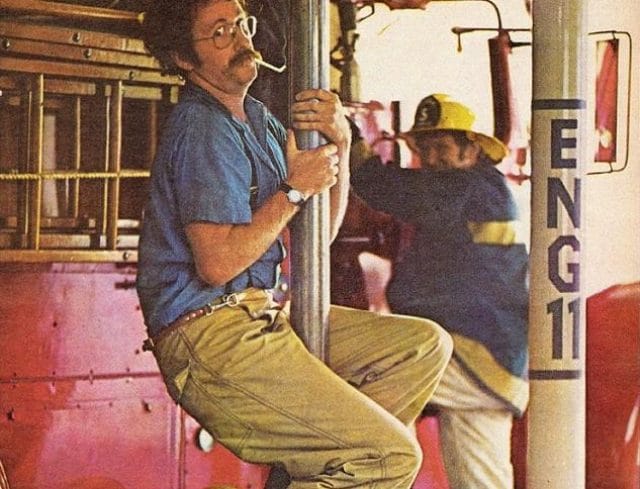

It’s a scene played out as many as three or four times a night in some large municipal firehouses, and no part of it is more central than the fireman’s pole. Since its invention and integration in the late nineteenth century, the fire pole has become a ubiquitous trope of the profession, right up there with the walrus ‘stache and the Dalmatian. On grade school field trips, it’s the coming attraction — a way to contextualize the exciting, perilous routine of men who put their lives on the line.

Once heralded as the time-saving successor to stairs, the fire pole is, after 150 years, sliding toward extinction. In its heyday, the pole revolutionized the way firefighters responded to alarms, accessed their trucks, and, ultimately, saved lives. But fire poles came — and still come — with a caveat: they have the potential to be lethal for those who descend them. A comb through archives reveals dozens of pole-related deaths, hundreds of serious injuries, and a slew of unsavory lawsuits resulting in multi-million dollar payouts. Today, an increasing number of firehouses are altogether abandoning the fire pole as they remodel old structures and re-analyze building and safety codes.

The story of the fireman’s pole is one of innovation, but also one of tragedy.

The Rise of the Fireman’s Pole

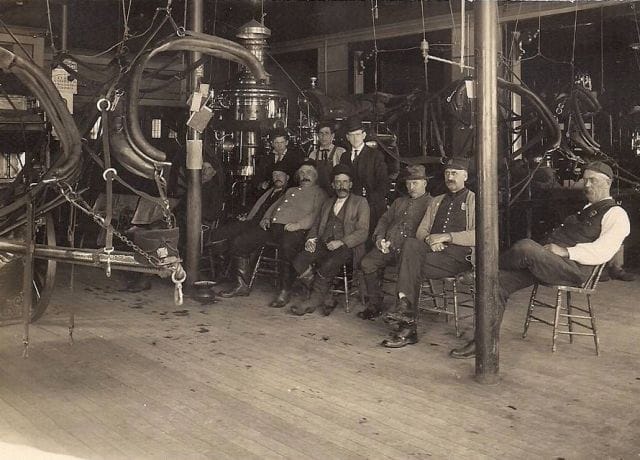

Firemen sitting by their pole (1905)

In 1736, Benjamin Franklin jump-started the first effort to build formalized firehouses. Over the following century, various tools would be implemented — buckets, hoses, ladders, and the like — but response times were brutally slow.

The majority of firehouses in the nineteenth century were two or three stories. Typically, the horse-drawn fire carriages (and horses) would occupy the first floor, the second floor would be the firefighters’ sleeping quarters, and, in some cases, a third floor would serve as a hay bale storage unit to feed the animals. Often, when the firemen cooked meals on the second floor, curious horses would ascend the stairs into the living quarters; as horses typically don’t descend stairs, they would then be stuck there.

To solve this issue, firehouses began installing narrow spiral staircases that the animals couldn’t access. This, however, led to a more pressing issue: when an alarm rang, anywhere from ten to twenty firefighters would all have to simultaneously scramble down these corridors to reach the trucks below. This invariably impeded response times; in an age where fire technology was limited, every second counted.

In 1878, one man’s inadvertent invention changed the way firefighters answered urgent calls.

One afternoon, David Kenyon, the captain of Chicago’s all-black Engine Company No. 21, was helping a fellow marshall stack hay on the third floor of his firehouse when an alarm rang. In the loft was a long wooden binding pole used to secure hay during transport; without a quick route of descent, Kenyon’s accomplice grabbed the pole and slid two stories down, easily beating out the dozens of firemen scrambling down the spiral staircase.

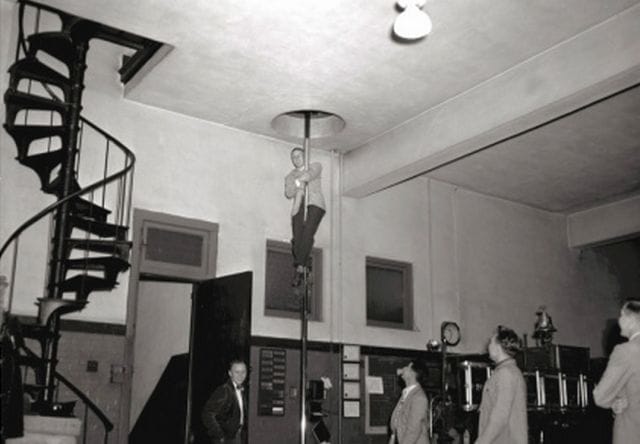

A much-loved fire pole beside its less-adored counterpart, the spiral staircase

Kenyon was intrigued, and saw great potential. The following week, he convinced the Chief of Department to approve the necessary building augmentations to install a permanent pole, and agreed to pay for any associated maintenance. A hole was cut through the two upper floors, and a 3-inch diameter pole crafted out of Georgia pine was installed; after several coats of varnish and paraffin, it was ready for daily use.

Following the installation, Kenyon and Engine Company 21 were mercilessly ridiculed by other firehouses. The team, claimed the naysayers, had lost its collective mind to merely consider such a strange response mechanism. But Company 21 quickly grew a reputation for being the first to arrive at the scene of a fire — often up to ten minutes before other brigades — and others slowly began to give the pole serious consideration.

After just a few months of operation, the Chief of Department ordered that poles be installed in every Chicago fire station. In 1880, the Boston Fire Department installed the first brass pole, and it became a standard for fire stations across the United States.

When Poles Go Wrong

By nature, firefighting is a generally dangerous profession, with an average of 116 deaths per year over the last 35 years (this data excludes the September 11 attacks). While stress-induced heart attacks and strokes are the leading issue, falls constitute up to 6% of all deaths, according to the U.S. Fire Administration. Historically, the fire pole has been a culprit.

As far back as 1885, there were recorded instances of firemen falling down fire pole holes or accidentally losing grip mid-slide — and dying. A rash of such incidents occurred throughout the early twentieth century. Combing through the historical archives of six major cities — New York, Boston, St. Paul, Los Angeles, Chicago, and Philadelphia — we were able to find 18 deaths related to fire poles from 1890 to 1930 alone (keep in mind that this includes only six out of hundreds of archives). The stories are varied: a young ladderman who fell 20 feet down a pole on the way to a call in 1904; a captain, Thomas S. Home, who awoke in the middle of the night and unwittingly walked over the hole in the floor and tumbled to his death; the Chicagoan auto engineer who slid down too fast, shattered his knee caps, and died from resulting infections a few months later.

Despite these incidents, safety precautions — railings around the hole, and mats at the bottom — weren’t widely implemented until the mid-1950s. Even then, the deaths continued. One such incidence in 1959 describes a St. Paul firefighter who tripped over his shoelace and went careening over the railing head-first 30 feet down the “pole hole.” It was the city’s fourth pole-related death. Another tragedy two years later in Boston saw a Lieutenant slip while descending and break his neck.

In the modern era, the frequency of deaths has diminished (there have been four since 2000), but safety measures have failed to reduce the plethora of injuries, both minor and major. A look through the Occupational Safety and Health Administration database reveals hundreds of fire pole related injuries over the past 30 years (1984-2014), ranging from broken ankles and toes to fractured skulls. Several of these incidents have led to graver consequences for firehouses and cities.

On December 23, 2003, Seattle firefighter Mark Jones awoke in the middle of the night to use the restroom and fell down the fire pole hole. A court document details the nature of his resulting injuries:

“Mark sustained severe injuries from his 15-foot fall, including traumatic brain injuries and extensive bodily damage. Mark’s brain injuries included a ‘diffuse axonal injury,’ a shearing trauma in which the ‘wires’ of the brain are ‘torn,’ and bleeding in his frontal lobe and ventricles. Mark fractured his pelvis in multiple places, many of his vertebrae, and nearly all of his right ribs. His lung was punctured, and his bladder ruptured. Mark later underwent surgery to remove handfuls of necrotic tissue that were preventing his lungs from expanding.”

Jones subsequently sued the city of Seattle for negligence and failure to install proper safety railings and was awarded $12.75 million in damages. In response, the city of Seattle banned poles and heavily invested in renovating all 32 of its local fire stations.

His case isn’t the only one: more recently, in March 2014, a New York firefighter brought a lawsuit against the city after sliding down a fire pole that was “too slick” and fracturing vertebra his lower spine. In the case, which is still undergoing review, he claims he was unable to control his descent of the pole, and relates that even following a string of such incidents, the firehouse failed to change its procedures.

Sliding out of the Picture

Whereas the fireman’s pole was once an iconic fixture at every major firehouse, it is increasingly being replaced today. With the advent of motorized vehicles and fire trucks, horses were phased out and there was no longer a need to have multi-level stations. Continued deaths and injuries, despite safety installations, have also led officials to reconsider the fireman pole’s role in the modern era. Harold Schaitberger, general president of the International Association of Firefighters, elaborated in an interview with The New York Times:

“It certainly is without any question that firehouse poles are becoming, with each new firehouse, a thing of the past. The new firehouse or station would be built with stairways and no poles.”

As firehouses around the nation uninstall fire poles, they fail to find alternative options to reduce response times. A few stations have experimented with another playground fixture — the slide — in lieu of the pole, but the trend hasn’t really caught on (imagine half a dozen 200-pound men trying to simultaneously shoot down a tube). Instead, many stations have come full circle — right back to using stairs. As a veteran firefighter notes, this is less than ideal: “Now at 4 o’clock in the morning, you’ve got 11 guys going down the stairs. Stupidest thing I ever heard of.” Ken Mulville, a station officer, contextualizes this sentiment in the vein of time management:

“It is ludicrous – we were all flabbergasted to find we will have to run down the stairs now. I would say it takes about half a second to slide down a pole and at least 20 seconds to run down two flights of stairs. At the end of the day seconds could be critical when responding to a [911] call.”

Though there are instances of serious injury, and even death, these instances are relatively infrequent when gauged with the sheer number of times firefighters descend the poles on any given day. But for firefighters, the argument for or against the pole always evolves into a moral dilemma: while it’s dangerous, it is, by far, the most practical and efficient method of responding to a call — often reducing response times by up to 30 seconds. One Massachusetts Lieutenant explains his catch-22:

“There is a pole in my fire station, and I consider it one of the most dangerous things we have in the building. There is a railing around the hole upstairs, but is only a horizontal rail about three feet above the floor, with three uprights holding it up. One misstep near that pole and its a 16 foot plummet. The 2″ landing pad at the base barely absorbs a controlled descent, let alone a fall.

That being said, I cannot think of a faster way of getting four or five people downstairs. It takes about a second and a half to slide and clear the pole. Five of us tumbling down the stairs is going to slow us down or roll an ankle. I use it every chance I get.”

Cost is also a consideration for municipalities renovating stations, or building new ones. With safety fixtures, a shiny new brass pole runs about $150,000 — far more than a concrete staircase.

So, where does the future of the fireman’s pole stand? The National Fire Protection Association (the overarching organization that sets standards and codes in place), has called for the removal of all poles from U.S. stations “due to safety hazards.” The organization hopes to phase them out completely as firehouses are remodeled into single-story units; the poles that do remain will be required to include safety enclosures and mats — “so nobody stumbles into it in the middle of the night,” as the association’s president puts it.

But the fireman’s pole is more than an outdated fixture: it’s one of the last reigning symbols of the antebellum firehouse. And for many firefighters, like NYFD Lieutenant Jeff Monsen, it’s a long-cherished tradition. “It’s the first thing I do when I work somewhere else,” he says: “find out where the pole is.”

If you found this blog post interesting, you’ll love our book → Everything Is Bullshit.

This post was written by Zachary Crockett. Follow him on Twitter here, or Google Plus here.