When Henry Charles, George Hankers, Jamie Searls, Aaron Foster, and Matt Brinkler step on stage, their audience goes wild. The five handsome singers belong to a hot British boy band, and they are currently on tour. They have headlined festivals, flown to Dubai to perform, and sold around 250,000 tickets. After each performance, hundreds to thousands of mainly teenage girls rush them for autographs.

Unlike other boy bands, however, the group does not have a top-of-the-charts single, and the five singers are not celebrities. They perform the songs of the boy band One Direction, but they are not One Direction. Rather they are Only One Direction: “the world’s best One Direction tribute band.”

Similar to how “cover bands” play hit songs written or popularized by famous bands instead of their own material, “tribute bands” do not perform original songs. Instead, they exclusively perform songs by the band they pay tribute to, usually mimicking the band’s appearance, style, and name. With Only One Direction, fans get to see a performance very similar to One Direction at a fraction of the price.

The success of Only One Direction is not an anomaly. While a few tribute acts are overzealous fans badly imitating their heroes, select tribute bands have enjoyed fame since tributes to The Beatles first sold out venues that once hosted The Beatles themselves.

Tribute bands got their name from their roots reproducing the experience of seeing a performance by a band whose members died or split up. Today, however, you can book a Coldplay, Adele, or even Justin Bieber tribute act. A surprising number sell out major venues in cities like San Francisco and Los Angeles, hire an agent, and even record albums.

Tribute bands make an obscene amount of business sense. It’s also unclear whether they are legal. Regardless, an increasing number of musicians seem to be enjoying the benefits of performing as second string music stars.

Tribute Band 101

As the name suggests, some musicians in tribute bands love the original band. But most join because tribute bands represents dependable income in a difficult industry. When we talked to Matt Brinkler of Only One Direction in between shows, he explained that singing as his One Direction counterpart “was meant to be bread and butter money. Pay the rent.” He and his bandmates treated it as a reliable side income that allowed them to keep working in the entertainment industry — in their independent careers, the One Direction singers have acting and commercial credits, a London radio show, singles and debut albums, and experience in dance groups and musicals. The unfortunate flip side, according to one individual in the California tribute band scene, is that other musicians who join tribute bands do so when their independent careers sputter. “With so many musicians coming to California to be rock stars, there’s a lot of talent from those that don’t make it,” he says.

So if you’re in either situation, how do you start raking in money by giving the people what they want?

One option — distinct from a tribute band — is a cover band. Cover bands play songs written or popularized by other performers and songwriters, usually a mix of crowd pleasers sung either in the original style or with the band’s own take on hit songs.

Bars often pay cover bands better than original acts since the promise of classic rock ‘n’ roll or funk usually trumps the draw of an unknown band. But tribute bands can make more per gig by offering people the next best thing to seeing The Beatles, Kiss, or Britney Spears live. “There’s no fame or glory in cover bands,” says Frank J. Moyer of AME Entertainment. “But in tributes, they treat you like the real deal.”

While a few tribute bands put their own spin on the music, almost all mimic the original band. They wear Kiss’s signature makeup, play with the force of Jimi Hendrix, or, in one extreme case, buy a plastic nose to more closely resemble Ringo Starr. Naming tribute bands after a famous song name or lyric (or a play on the artist’s name) has become something of a standard: Sgt. Peppers is a Beatles tribute band, the East Street Shuffle plays the music of Bruce Springsteen, and Bon Jovi’s lawyer once sent Blonde Jovi a cease and desist letter.

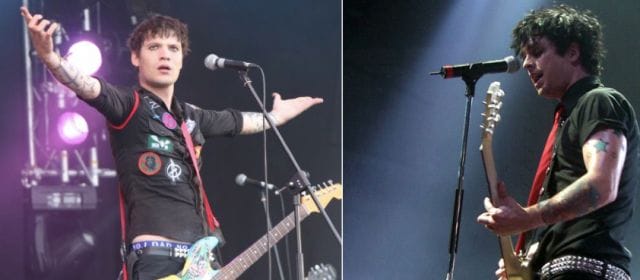

The lead singer of Green Day and its official tribute act Green Date. Source: Wikipedia

Both cover and tribute acts get legal permission to play someone else’s music in the same way.

Since it would be a nightmare for every bar and concert hall in the country to negotiate permission for each night’s set, a few middlemen, known as performance rights organizations, exist to grant licenses and collect royalties on behalf of singers, songwriters, and music publishers. There are 2 primary middlemen in the U.S., Broadcast Music Inc (BMI) and the American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers (ASCAP).

BMI and ASCAP charge venues according to a formula that uses factors like the size of the space and the number of weekly performances. It usually comes out to a few hundred to a few thousand dollars per year, except at concert halls that pay a fraction of a percent of the cost of each ticket. That money goes into a giant pot of funds that includes revenue from sources like TV commercials and radio play, which the organizations then distribute to songwriters and music publishers based on estimates of how frequently each song is played.

Many bars don’t realize they need to pay for permission to host a band playing a few AC/DC songs (and cafes and stores often don’t realize that they have to pay to play CDs). So agents from BMI and ASCAP cross the country to educate them, while lawyers back up that education with legal threats that angry owners often compare to shakedowns.

But as BMI and ASCAP represent almost the entire catalogue of copyrighted work, once a venue has paid them, it can play any music in any format, whether that means pushing play on a Spice Girls CD, paying a cover band to play hits from the eighties, or bringing in a Kiss tribute band.

In Britain, in contrast, cover and tribute bands send a performing rights organization a list of every song they will play, which is used to calculate a licensing fee. Matt Brinkler says that about £1 of everyone’s £15-£20 ticket goes to rights holders, of which about 3 pence gets to the One Direction boys themselves. (Bands have to detail the length of each song down to the second, so you can be sure that Only One Direction’s encores are always well planned.)

Since just 2-3 organizations license bands and venues, the process is heavily regulated. BMI and ASCAP must provide what are known as blanket licenses, meaning that they automatically grant licenses to anyone willing to pay a standardized fee. As a result, bands don’t need to ask permission to “pay tribute,” meaning there’s almost no barrier to starting a tribute band.

But while it’s easier to make it as a tribute band than as an original act, tribute acts still have to start at the bottom. “It was bright daylight, nothing posh,” Brinkler recalls of Only One Direction’s first show, which took place in a gym cafe. “We could barely fit on the stage.”

Although the appeal of a tribute band is a lower price tag, good tribute bands don’t fill their schedules with birthday parties and bar mitzvahs. “The price tag is just a little too high for private parties, but we’ve done a few birthdays,” says Brinkler. Michael Twombly of Music Zirconia, a San Diego based tribute band booking agency, describes bars that fit 200-1000 people as typical venues. He also cited corporate conferences and parties as staple tribute band business.

A good tribute band, however, has the potential to land in front of large audiences very quickly. After all, everyone already knows the music. They don’t need to create a fan base; they just need to prove they can satisfy the expectations of the huge, hungry fan base that already exists.

Only One Direction was soon playing nearly day. A year and a half after their first rehearsal, the singers performed for 10 thousand screaming fans on the main stage of Gravesend’s Party on the Prom. They shared the day with tribute bands like Coldplayer as well as original acts. “It was rammed. Sold out,” says Brinkler, who was taking a breather from touring at the time. “They headlined. It was brilliant.” Twombly describes tribute bands playing in venues ranging from small bars to fairs, festivals, casinos, cruise ships, and soccer stadiums, including a 15,000 person show in Dallas that is just for tribute bands.

Performers in Only One Direction’s situation straddle the border between rock star and struggling artist. Says David Ribi of Only One Direction:

“I think the best way to describe it is to say it’s like being in a flash mob. There’s all this greatness and craziness when you’re on stage and then as soon as you’ve done the meet and greet afterwards — everything goes back to normal.”

Musicians in popular tribute bands may hire an agent or producer (if they don’t already have one), they can expect fans to sing along at every concert, they can tour full-time, and they can even record albums by buying something called a “mechanical license” that works similarly to the licenses for performances.

On the other hand, they don’t get the full rock star treatment. The money is good — producer Anna Slater says the band has earned six figure revenues during its roughly 2.5 years of performing, and Brinkler calls it “great money” — but it will never be set for life good. (A famous band can command $100,000 to $1 million per performance; very elite tribute bands seem to peak in the low six figures.) The members of Only One Direction also split tasks like marketing and PR, logistics, and costuming, and they don’t have a fancy tour bus. “We say, ‘Woohoo, success!’ Then we get back into the car and drive,” says Brinkler. “I don’t know how small cars go over there [in the U.S.], but cars go damn small here and we’ve got 5 guys.”

Playing in Only One Direction hasn’t led any of the members to retire to a lifetime of playing tribute; they all continue to work on other projects. But they seem to appreciate the success of Only One Direction. Brinkler says the band mates are inundated with job offers, and while they pursue some, they have even turned down record contracts to keep working with Only One Direction. “We went from barely fitting on the stage to a massive arena,” says Brinkler. “Who gets that type of chance?”

From Beatlemania to Biebermania

The music industry generally credits two performers for inspiring the tribute band trend: Elvis Presley and The Beatles.

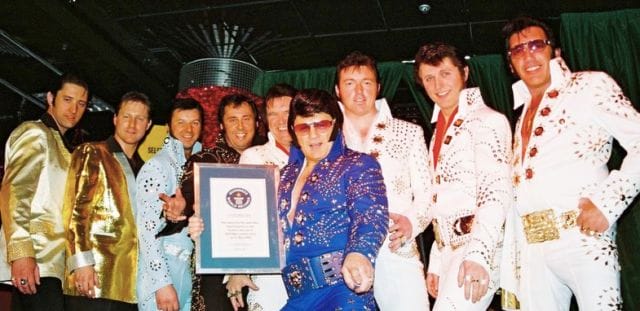

Elvis contributed by making it a thing to imitate a celebrity performer, as literally hundreds of thousands if not millions of fans have belted out hits like “All Shook Up” while shaking their hips in a snug, bell-bottomed suit. But the Beatles put tribute bands on the map. “It might have been Beatlemania,” Twombly reflected. “People had been doing [tribute bands], but it never took off until Beatlemania.”

Setting the world record for most Elvis impersonators in 2005. (Most impersonators not shown.) Source: Wikipedia

It all started on Broadway. In 1977, seven years after the Beatles last performed together, a “rockumentary” called Beatlemania premiered in Boston. It spread to New York, then across the country. In each city, the producers cast one to two teams of musicians who could perform as The Beatles during the performance, essentially creating a flood of potential Beatles tribute bands.

When the play ended after a successful run, members of the various casts formed the first tribute bands and played recreations of live Beatles performances in major venues across the country. Carlo Cantamessa, who portrayed John Lennon for 30 years between the play and a tribute band called The Cast of Beatlemania, described the concept in an interview:

“The Cast of Beatlemania originated out of the Broadway show Beatlemania, but we took it one step further where we try to look, act and sound like The Beatles as you remember them”

You can still see The Cast of Beatlemania perform today. At $40 to over $80, tickets often go for as much as active, original bands.

With the precedent established, classic acts like Led Zeppelin, the Grateful Dead, Queen, and many others inspired tribute bands, especially when they ceased touring. (One British journalist has asserted that Australia acted as the “main cradle of the tribute band,” as the wayward continent was forced to produce local versions of beloved bands that never visited.) Like the Cast of Beatlemania, the most successful make a living by touring full-time, often filling major venues.

Tribute bands have been rocking for decades now, but they seem to have taken a leap in popularity over the last ten odd years. Michael Twombly, whose booking site receives around 25 submissions a day from tribute bands that want to be listed, says that calling his site the largest agency for tribute bands is a “small brag” — it’s still boutique size by industry standards. Yet he says there were “not a lot” of tributes when he started his site 7 years ago, but now it has “exploded.” In an interview, Lenny Mann of tributecity.com has seen the same rise in popularity since 2000. Brent Giles Davis, a lawyer and former tribute band player, cautioned that tribute bands could just be easier to find thanks to social media. Yet, he says, “Anecdotally I do see more tribute bands showing up on the schedules of mid size venues.”

One way the number of tribute bands has grown is in creating tributes to young bands. Today, with the world boasting Justin Bieber bands a plenty, tribute bands’ origins as a way to recreate live performances of bands that no longer tour is less relevant. Beatles tribute bands continue to be the most popular, but more and more, tribute bands offer a budget alternative to a new, hot band. “We get quite a lot of comments about why we’re a tribute when they’re not even dead yet,” Matt Brinkler tells us. “One Direction has been going for 3 years and so have we.”

This makes a lot of economic sense. Over time, profits in the music industry have concentrated in the hands of a few “superstars.” Whereas musicians could only entertain a room full of people at a time in the age before music recordings, technology has allowed Justin Bieber, Beyonce, and Coldplay to entertain the entire world simultaneously through CDs and digital downloads. But they still can only perform in one venue at a time. Until bands start playing 10 locations at once via hologram, tribute bands are an obvious solution, with the glut of musicians who fail to establish their own band providing an ever-ready supply of talent.

This is exactly what Anna Slater does. She founded her production company Pink Productions 10 years ago when she saw an opportunity. Tribute bands were popular, but no one was doing young, current groups. Starting with the Pussycat Dolls, she “got on the bandwagon.”

When One Direction became famous on The X Factor, a televised British singing competition, Slater decided that she “had to get onto this one.” She held auditions in London and Manchester, and after a “very stressful six weeks” of rehearsal, Only One Direction did its first performance in a gym lounge. “It was so long ago that One Direction didn’t have enough songs to fill an hour show,” recalls Brinkler. “We did 20 minutes of One Direction and filled the rest with Bruno Mars and other boy bands.” One Direction didn’t even have an album yet.

At Matt Brinkler’s suggestion, Only One Direction took the step of becoming “not just a band but a brand.” Matt and four other singers tour under the name Only One Direction. Simultaneously, five others take gigs as Only One Direction. Four alternates also cycle through, allowing the performers to take breaks and the band to perform more frequently. It’s a commoditized band on a high level — “a product,” says Brinkler.

An Infringing Performance

One of the more impressive aspects of tribute bands’ success is that they’ve done it while breaking trademark law with impunity.

Although tribute bands perform at venues that have purchased licenses from performing rights organizations, those licenses are intended for use cases like playing the radio and hosting cover bands. In the United States, these licenses fail in the tribute band case in two ways.

Firstly, bands make little to no money from their tributes. Brent Giles Davis, a lawyer who used to play in a Springsteen tribute band, gives the example of Phish. BMI and ASCAP give out blanket licenses because it would be difficult to measure how often each and every song is played in America’s 65,000 bars and nightclubs. Instead, they distribute royalties by using how often songs are played on measurable mediums like radio and television as a proxy. As Phish is popular live but not on the radio, it receives almost nothing.

Secondly, licenses compensate the publisher and songwriter, not necessarily the band itself. Many singers and bands popularize songs written by others. As Davis tells us, “I think Sinatra wrote one half of a song in his entire life, so no money from Sinatra tributes would get to him.” It seems reasonable to only pay the songwriter when a cover band performs a song Sinatra also sang, but it seems unfair that a singer dressed as Sinatra, singing like Sinatra, and promising an audience a Sinatra-like performance would contribute nothing to Sinatra.

“As far as I can tell, tribute bands currently fly under blanket licenses,” says Giles. Yet under those licenses, venues and bands don’t compensate the original band despite the performances popularity deriving from mimicry and taking advantage of the original band’s reputation.

This is exactly why bands could sue tribute bands for trademark infringement. Even though audiences know that Sgt. Pepper is not the Beatles and that Blonde Jovi is not Bon Jovi, the fact that tribute bands’ imitation has the potential to mislead — and benefits from the “goodwill” a band has engendered with the public — means that it is copyright infringement or violates similar legal rights such as performers’ “right of publicity.”

A Beatles tribute band performs. Source: Wikipedia

So why aren’t tribute bands sued out of oblivion?

Trademark infringement is a federal case, which as Brent Davis tells us, means expensive litigation. A band would spend $150,000 or more for an injunction, the potential damages may not be that high, and stopping each tribute band requires a separate lawsuit. “It’s not worth the time or the money,” says Davis. “When you’ve stopped one tribute band, what about the other fifty?”

Threatening legal action is much cheaper, which is something bands are known to do. (“The Journey guys can be tough,” says Michael Twombly, who helps book tribute bands. Their lawyer will hassle you in California.”) Occasionally it makes bands stop playing. More often, they change their name or stop using the logo and keep playing. (We did not research the legal scenario in England, but Anna Slater says that she believes that the trademark issue is different in the U.S. and says that Only One Direction has its own logo and pays attention to licenses.)

Tribute bands also escape lawsuits because litigiousness doesn’t do wonders for an artist’s image and, according to Twombly, most bands think it’s neat to have tributes. Many artists “come sit in” to see if the tribute band is any good. Twombly quotes Elton John saying of an Elton John tribute, “Oh, he needs to work on this here, but otherwise he’s doing a fine job.”

The lines between tribute band and original band can also blur. In 1995, singer Tim Owens went from lead singer of a Judas Priest tribute band to the lead singer of Judas Priest as he replaced its departed frontman. Other times, one or two members of a band that broke up will form a band with other musicians. John Kadlecik, for example, was the lead singer of Dark Star Orchestra, a famous Grateful Dead tribute band. He then joined two Grateful Dead members to form Furthur, a band that plays Grateful Dead songs, original work, and other covers.

American tribute bands may one day face reforms that make them compensate the original band at a higher rate or seek permission. But some artists aren’t waiting for the industry or the law to make that happen. Several artists have blessed one tribute band as their official tribute band. For some famous artists, the motivation is to make sure a band playing their act keeps up the quality. But there’s also a financial interest. Several members of Queen, for example, put together their own tribute band, The Queen Extravaganza. They are producers of the show, so they profit off the band. “Not many young people saw Queen live,” Roger Taylor of Queen told Rolling Stone. “So this is a chance to do the closest thing and see a very good facsimile.”

Second String Music Stars

“Looks and sounds like the real thing! (Just less expensive)” ~Music Zirconia pitch for tribute bands

The great selling point of tribute bands is getting to see a performance by a favorite band at a lower price without fighting over a small stock of tickets. According to Jeff Economy, director of a documentary about tribute bands, “The more you can be a carbon copy, the happier the audience is going to be.”

As a result, a fair amount of stigma surrounds tribute bands. “The first year, I would say and most of the boys would say, ‘I’m gigging,’” recalls Brinkler of Only One Direction. “People would ask and we’d say, ‘Boy band stuff. Just gigging.’” He describes the reputation of tribute acts as “tacky, cheap, you can’t get any other job.” Michael Twombly adds that even with tribute bands playing at festivals, “It happens not infrequently that we schedule a tribute to open [a concert] and the other band’s manager calls and says ‘We don’t want a tribute opening for us.’”

Aware of the reputation of tribute performers as tacky and untalented, Anna Slater, Only One Direction’s producer, is at pains to stress that the band sings live and that a lot of time and money goes into rehearsals and production. For his part, Matt Brinkler says that while you would “probably not” announce your tribute band experience at a musical theater or in a meeting for a record deal, he doesn’t think it’s harmful to a career. The band’s success has led the singers to receive many great job offers, and he believes it’s great experience for singers to develop their stage presence. One band mate even plans to go on The X Factor and say “I’m Niall in a One Direction tribute band and I’m better.”

It’s true that while some tribute bands put their own spin on the music — Dread Zeppelin achieved fame playing Led Zeppelin in a reggae style — it is much easier to sell audiences on hearing their favorite band’s songs, performed faithfully. But that shouldn’t make you look down on tribute bands.

Performers like Sinatra, after all, sang songs written by others. In an article on tribute bands, one frustrated tribute band member riffs, “Look, even symphony orchestras are tribute bands! They didn’t write that stuff! They do Beethoven and Tchaikovsky covers. But no one sends them hate mail like we get.” There’s still plenty of room for creativity and entertainment through great performances. Brinkler says Only One Direction has different moves and sets for every show, and he happily mentions “doing a solo the other day, and one of the other boys jumped on my back and we carried on like that.”

More sensitive to its audience without the protective insulation of celebrity, tribute bands can also excel at giving fans what they want. No tribute band has ever refused to play its hit song. When One Direction started wearing darker colors and “going in this growing up direction,” Brinkler says Only One Direction initially imitated it. “But the audience didn’t buy it. It’s not something they wanted.” So now they “focus on the One Direction that people expect.” They keep wearing bright colors and giving high energy performances. Or to put it in terms that One Direction fans will appreciate: “One Direction has never jumped up and down on stage for 90 minutes straight.”

The establishment of Only One Direction as a “product” and a tribute brand rather than tribute band is decidedly unromantic. It sounds like Henry Ford reinventing the music industry. But tribute bands consist of entertainers who want to delight their audience.

“We all know we’re not One Direction,” says Brinkler. “But we’re performing this music, all live, and we hope you’re loving it as much as we do.”

This post was written by Alex Mayyasi. Follow him on Twitter here or Google Plus. To get occasional notifications when we write blog posts, sign up for our email list.