This post is adapted from the blog of Udemy, a Priceonomics customer

![]()

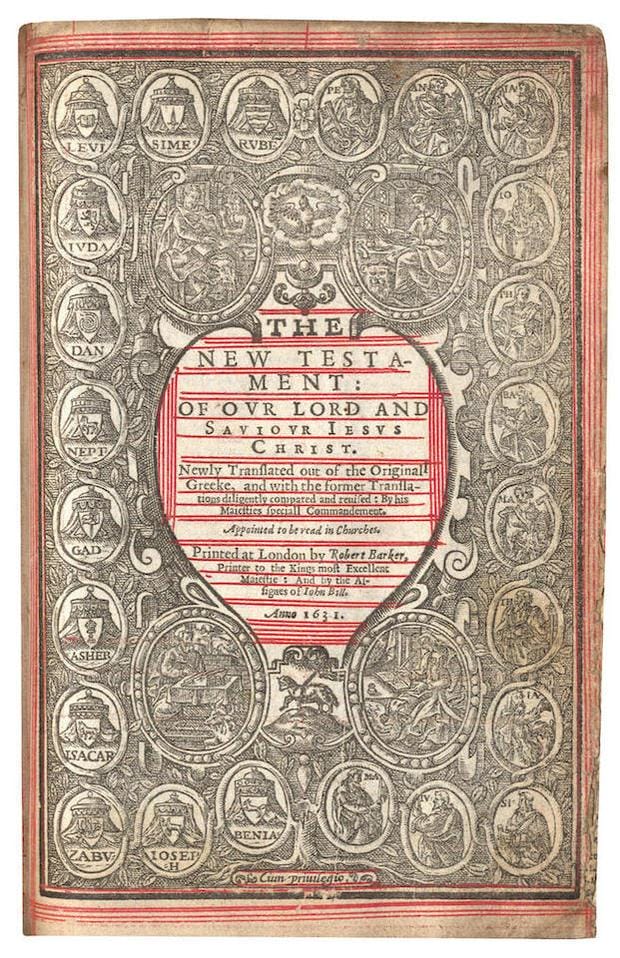

Last month, a highly unusual Bible sold at auction for a whopping $47,311.

From its exterior, the book looks rather unassuming: It lacks a general title. It contains only two colors of ink — black and red. Its pages are jagged and frayed, as if cut with a hacksaw.

Yet deep inside this 1631 copy of the King James Version, nestled in the Ten Commandments, lies what is widely considered to be the worst typographical error ever made in a Bible. It is so bad that the text has become immortalized by collectors as the “Wicked Bible.”

The story of this so-called “Wicked Bible” presents an interesting visage into the past, when a lone typo could, quite literally, cost you your life.

***

For early English Bible scholars, translation was a very risky business.

The first complete English translation of the Bible was carried out in the 1380s by followers of theologian John Wycliffe. Pre-dating the printing press, copies of this text were individually inscribed by hand. After Wycliffe criticized the Church and was denounced a heretic, it was proclaimed that anyone caught with a copy would be put to death. Nonetheless, this version continued to be produced, and was widely circulated into the late 15th century.

In 1525, a scholar named William Tyndale created a second English translation of the New Testament, this time taking advantage of the newly-invented printing press. Before long, his “objectionable” translations (substituting “church” with “congregation” and “priest” with “senior”) had priests’ panties in a bunch: copies were rounded up and burned, and then Tyndale himself was defrocked, strangled, and burned at the stake.

William Tyndale was burned at the stake, in part for his faulty Bible translations; image via Wikipedia

Despite the apparent risks in translating, seven other Bibles were produced throughout the 1500s, most of which fell out of favor with the Church of England, and led to negative outcomes for publishers.

When King James I took the throne in 1604, he immediately ordered that a new translation of the Bible be commissioned. To accomplish this, he enlisted 47 scholars — all clergy members of the Church of England — and divided the text’s chapters between them. By 1611, the King James Version (known then as the “Authorized Version”) had been completed.

Image via Bonhams

At the time, very few publishers had the ability to print the Bible, and even less wanted to risk taking on the job and messing it up. But one very ballsy man decided to assume that risk: Robert Barker.

Barker was born and bred to be a publisher. His father had been granted the title of “royal Printer” by Queen Elizabeth I, a duty that came “with the perpetual Royal Privilege to print Bibles in England.” When Barker’s father died in 1599, he inherited this business and took over all publishing duties. Over the ensuing decade, he continued to establish a formidable relationship with the Church, publishing official prayer books and scriptures.

In 1611, Barker printed the first edition of the Authorized Version — a looseleaf that sold for ten shillings. Though Barker marketed his printing as “Authorized,” the king himself had not, in fact, approved the copy. Generally, the public regarded it as poor work: the type was hideously uneven, the font was difficult to read, and the entire book was peppered with hundreds of typographical errors. The version did not sell well at first, and Barker, who’d “invested very large sums” in publishing it, soon ran into debt.

Consequently, Barker had to enlist the help of two rival publishers: Bonham Norton and John Bill. As printing continued, serious disputes about profit distribution ensued. The printing of the King James Bible became a competition between these publishers: over the next two decades, multiple versions were printed off, each of a decidedly lower quality than the last.

Source: A Textual History of the King James Bible (David Norton, 1993)

“It [became] a tale of commercial enterprise that was not always competent,” writes Bible historian David Norton, “and standards of proof-reading were not particularly high.”

Given the scope of the King James Bible, errors were to be expected. The text was between 1,500 and 1,600 pages and contained all of 788,000 words — 12,000 of which were unique. Formatting this behemoth was an equally formidable endeavor: it was riddled with thousands of numbered verses, asterisks, and indentations. Still, the profusion of errors in the text was hard to justify.

Versions released between 1611 and 1630 contained some 1,500 misprints, ranging from blatant spelling gaffes to capitalization and punctuation issues. Sometimes, these entirely changed the meaning of the text: in a 1617 version, for instance, the word “God” was mistakenly replaced with “good” multiple times.

Amidst this Bible printing frenzy, one of the most infamous typos in history was made.

In 1631, Barker pounded out another poorly edited King James Bible. Unfortunately for him, it would prove to be his last. Smack dab in the middle of the Ten Commandments (Exodus 20:14) — one the the Bible’s most integral passages — the publisher omitted one crucial word: “not.”

Image via Bonhams

The passage, which should have decried adultery, now, as clear as day, commanded the reader to engage in extramarital affairs: Thou shalt commit adultery.

Nearly a year passed before the Bishop of London discovered the typo and brought it to the attention of the king. By this time, King Charles I was the new ruler, and he did not take kindly to the news.

Outraged, the king had Barker rounded up and brought before him in the Star Chamber, the court of law at the royal Palace of Westminster. After flipping open a 1631 copy of the text to prove that the pair had overlooked the typo, the king immediately revoked his printing licence, fined him a sum of £300 (the equivalent of $68,476 U.S. dollars today), and threw him in jail. Barker eventually died behind bars.

The Archbishop of Canterbury, who’d been disgraced and criticized as a result of the typo, was furious, and delivered what is surely one of the earliest and most passionate rants about grammar in history:

“I knew the time when great care was had about printing, the Bibles especially, good compositors and the best correctors were gotten being grave and learned men, the paper and the letter rare, and faire every way of the best, but now the paper is nought, the composers boys, and the correctors unlearned.”

With great haste, the King’s Court made its best attempt to round up all of the afflicted copies (estimated to be around 1,000) then burned them.

A 1631 “Wicked Bible”; image via Antiques.gift

Some historians have surmised that the omission of “not” was intentional — a premeditated act of sabotage by one of Barker’s competitors, meant to ruin his career. “Certainly the controversy added to Barker’s decline in fortunes and reputation,” writes London-based auction house Bonhams. “A mistake seems slightly unlikely. If you’re going to check 10 things, then you’d think you would check that page.”

Bonhams, which recently sold a copy of this so-called “Wicked Bible” for more than $47,000, estimates that only 9 such copies remain in existence. At least 5 of these copies are buried away in museums and libraries across the U.S. and England (New York, Alabama, Texas, London, and Cambridge) and are rarely made available to the public. Since World War II, only 5 copies have been sold, ranging in price from $240 (1979) to $89,500 (2010).

Once condemned, the worst Bible ever printed has become a highly sought-after collector’s item.

![]()