Editor’s note: Unless otherwise stated, all names in this article have been changed.

![]()

On a short stretch of Market Street, sandwiched between the headquarters of Twitter and Uber, one of San Francisco’s most lucrative economies runs its daily course. Here, in the street, men lean against walls in the shadows, muttering their wares to passersby:

“Weed…Hey, you want some marijuana, man?…I got Addies…Roxies…”

In many ways, they are consummate salesmen: To evade patrolling cops, they often rely on subtlety rather than obtrusiveness. They are experts at identifying their customer base. They realize, just as lucidly as the men in the offices above them do, that if a product is good enough, it doesn’t need to be heavily marketed.

Throughout the city of San Francisco, there are hotspots for certain drugs. Venture to Haight-Ashbury, and you’ll find a variety of psychedelics, ranging from psilocybin (“shrooms”) to the mind-bending Dimethyltryptamine (DMT). In the Tenderloin, just a few paces from the police station, crack, heroin, PCP, and even bath salts can be had — sometimes all from the same dealer. On Market Street, the specialty is weed, though with a bit of querying, a wide variety of prescription pills are ripe for purchase.

These illicit drug sales represent a massive market in the city — one with an estimated value of $400 million. Despite this market’s open-air nature, its economics are largely underground: only those who are a part of the network understand the complex menu of prices.

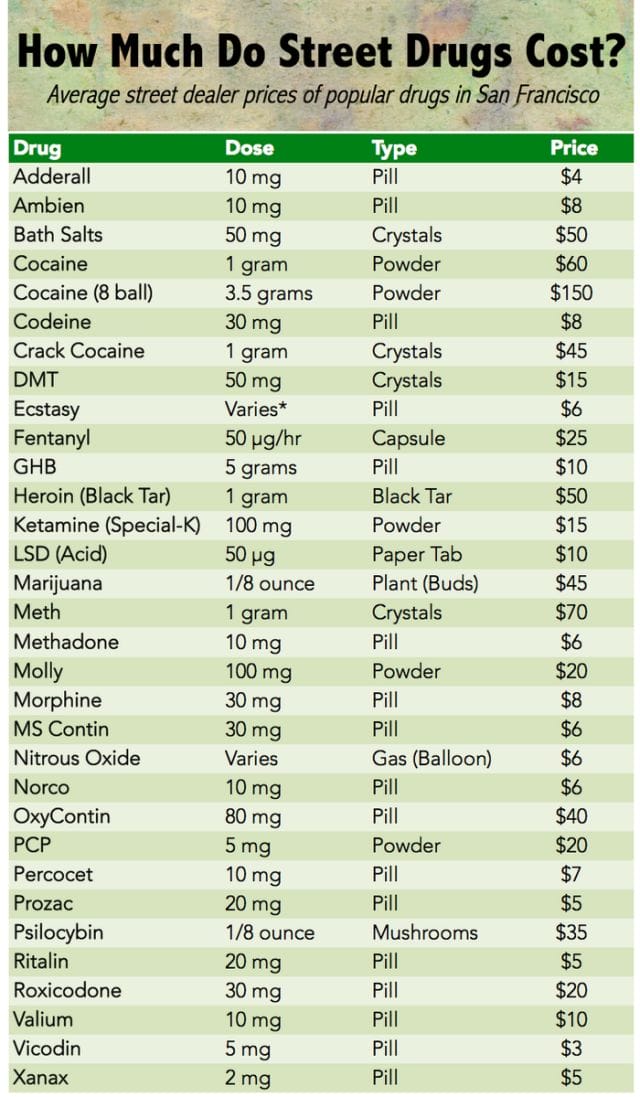

To better understand what drugs cost on the street, we decided to talk to a few ex-drug dealers and users who are familiar with the city’s drug landscape. We then took their answers and cross-referenced them with drug pricing discussion forums, like r/Drugs, Erowid, Streetrx, and Bluelight.

Obviously, there is a wide range in price for any given drug, depending on a number of factors: who you buy from, how good your hook-up is, the drug’s purity and quality, and even the day of the week. The prices below represent averages for common drugs in the city, as purchased from a dealer on the street.

*Ecstasy pills typically mix MDMA with caffeine or another substance, and purity levels vary; all pill listings here represent one unit.

Typically, prescription pills are the cheapest, ranging from $3 to $7. Since these pills are so cheap, turning a profit is all about moving big volumes.

“Most of the time, the pill dealers are moving 10 or 20 pills per sale,” Cody, an ex-street dealer, tells us. “If you know what you’re doing, you can usually make around $800 in a day…one year, during the Gay Pride Parade, I made $2,500 in three hours.”

Pill dealers are particularly apt at identifying when users are going through a withdrawal, and use this information to toggle the price. “If someone looked sick,” says Cody, “I’d charge them twice as much.”

It’s easy to get a script for anything — the hard part is finding a “shady” doctor who is willing to both reliably supply the pills and completely abandon any faithfulness to the Hippocratic Oath. For Cody, one fruitful connection led to a formidable business operation.

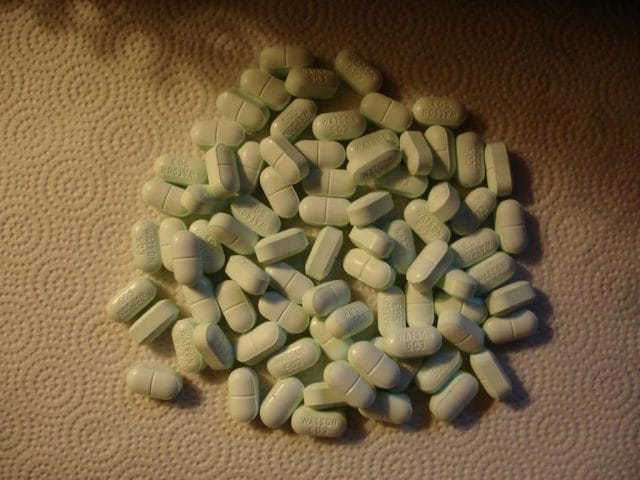

Vicodin pills exchange hands in front of Episcopal Community Services, a homeless resource center at Howard and 8th Streets; Photos: Zachary Crockett

Ecstasy, a man-made pill, is also particularly lucrative.

“There aren’t many manufacturers,” says Bryce, an ex-user/dealer. “The people producing them are making them in the hundreds of thousands.” Back in the day, Bryce would buy 1,000 ecstasy pills at a time (known as a “boat”) for $3,000, flip the majority of them for a profit, and still have enough left over for his personal use.

A once-ubiquitous club drug combining 100-200 milligrams of MDMA with “uppers” (amphetamine, caffeine, etc.), ecstasy has since been usurped in popularity by Molly, a pure MDMA equivalent. Likewise, OxyContin, an opiate that is released gradually over a 12-hour time period, has been upped by Roxicodone — essentially the same drug, except with a much shorter kick-in time.

While pills generally hover around similar price ranges, “harder” drugs fluctuate tremendously, mainly based on purity.

“In the Tenderloin, you get can dope [heroin] for $40 to $50 per gram — but they cut it up so much that it tastes like vinegar, smells like shit, and barely gets you high,” says Bryce. “If you buy from a dealer you know, it’s more like $100 per gram, but the quality is much, much higher.”

Cocaine and crack present a similar case. While both are essentially the same drug, one is considered “purer” while the other is more commonly adulterated and cut with chemicals. “Crack doesn’t have much pure cocaine in it,” one user tells us, “but you can consume less of it and get equally high as you can with cocaine, and it’s cheaper.”

In San Francisco, there also exists a strong psychedelic contingency — a group of explorers known as “psychonauts.” Randy, a 27-year-old who has since stopped using, was once a regular user of Dimethyltryptamine (DMT), a drug capable of “transmitting users to a dimension of reality that you couldn’t even imagine.”

“There isn’t too much DMT on the street — usually, you just get it from friends,” he clarifies. “Psychedelics generally attract very intelligent people who are interested in chemistry, and who want to explore the mind a lot.”

With a little guidance, drugs like DMT can be synthesized relatively easily at home, but measuring doses requires relatively high-powered scales that measure down to the 1/100th of a gram. “This stuff is so powerful that the difference between .05 and .08 of a gram is the difference between being okay, and being completely fucked,” adds Randy. “You really have to be careful, or you might not come back the same.”

On the other end of the spectrum, dealers of weed (arguably the city’s least harmful drug) are usually fairly liberal with their measurements.

Bryce, the aforementioned ex-pill dealer, also once dabbled in dealing weed on Golden Gate Park’s “Hippie Hill.” He never carried more than one ounce on him at any given time. From a large bag, he’d eyeball the typical purchase — one-eighth of an ounce — and covertly dump it in the customer’s hand on a side-street.

Bryce typically carried no more than a “zip” (or an ounce) of weed at any given time

Using this method, he often gave out extra, but avoided the brunt of legal danger: In California, if you’re caught with any amount of weed up to one ounce (28.5 grams) for personal use, it is only an infraction that comes with a $100 fee; if you’re caught with an intent to sell (including pre-distributing your weed into little baggies), you can be charged with a felony that is punished with thousands of dollars in fines and up to five years in jail. By staying “smart,” Bryce was able to turn a decent profit.

“You buy maybe five or six ounces at a time, for $150 each,” he says, “then break them into eighths, sell for $40 to $50 each (more for tourists), and get about $200 in profit per ounce.”

Bryce’s prices are typical on the street, though it’s not unheard of for eighths to go for as little as $30 and as much as $75, depending on the strain. This range is fairly consistent with San Francisco’s approved medical dispensaries, where prices range from $35 to $80 (for secret, or more potent strains) — though in general, the city’s dispensaries offer weed that is both cheaper and of a higher quality than the average bud sold by people like Bryce.

“I was selling Mexican stuff,” he admits. “Obviously, it wasn’t as good as what you’d get in a club, but I charged more because the market rate is different on the street. Most people buying out there aren’t looking for an artisanal experience; they just want to get high.”

***

In San Francisco, 13% of all residents report regularly using recreational drugs — 5% higher than the national average. The city has been unequivocally deemed “number one” for drug use in studies conducted by RAND and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration — and contrary to popular belief, it’s not just junkies who are fueling this market.

Rehab centers around the Bay Area have reported an increase in upper middle class entrants, many of whom work in tech.

“I’ve had [people] from Apple, from Twitter, from Facebook, from Google, from Yahoo — it’s bad out there,” one addictions coach told The San Jose Mercury News. “And it’s a lot worse than what people think because it’s all covered up so well. If it gets out that a company’s employees are doing drugs, it paints a horrible picture.” She estimates that she’s helped more than 200 tech workers get over addictions to “everything from cocaine and heroin to painkillers likeo oxycodone and stimulants like Adderall.”

Prescription opiates like hydrocodone are widely administered in the San Francisco Bay Area — and widely abused; via johnofhammond (Flickr)

“What I’m seeing at meetings is a lot of people getting hooked, courtesy of their doctors,” another worker adds. “You see very few of the old-school addicts; most of these are college-educated folks who either started abusing pain meds after an injury, or because of the stress of these tech jobs they start doing cocaine to stay up and oxycodone to relax. Working 80-hour weeks and making crazy money extracts a terrible toll on you.”

Bryce corroborates this: “When you’re dealing, you see all types of people — guys in suits, lawyers, programmer types,” he says. “There’s no one type of person who buys drugs. At the end of the day, they’re all just looking for a fix.”

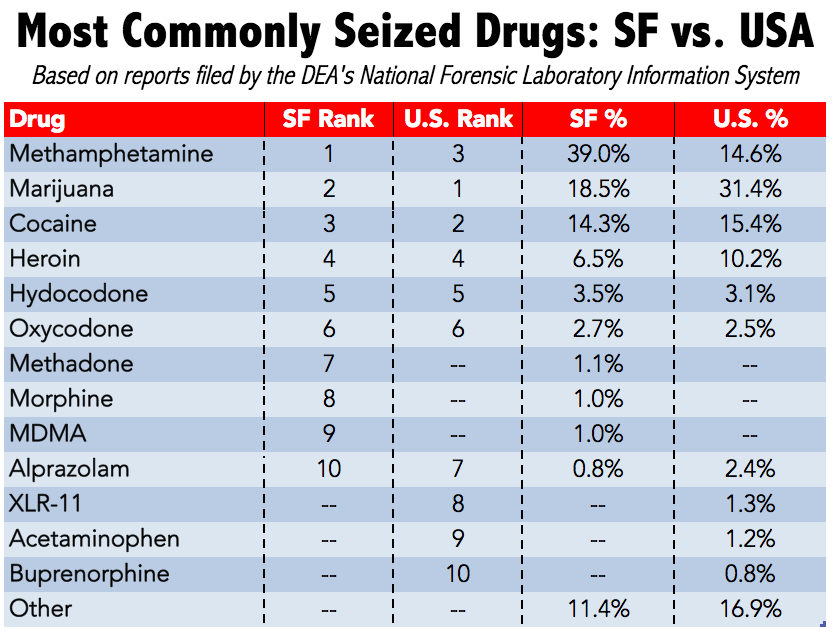

Though it is nearly impossible to quantify drug use in any given municipality, a rough idea of which drugs are more popular can be had through examination of DEA seizure data. According to the National Forensic Laboratory Information System, methamphetamine has a stronghold over San Francisco — but prescription pills dominate the list of most commonly found drugs:

Data via the DEA (National Forensic Laboratory Information System)

According to the National Institute of Drug Abuse, the city by the Bay is particularly pill-crazed. Between 2011 and 2013 alone, 5.1 million hydrocodone prescriptions were handed out by doctors, in addition to 370,216 for codeine, 221,208 for morphine, and 271,285 for oxycodone. All of these are highly addictive opiates.

“I felt bad about selling stuff,” admits Bryce, “but the pharmaceutical companies should feel bad too. They’re usually the ones getting people hooked in the first place, and they do it without the fear of going to jail.”

***

For our next post, we examine the strategic merits (or lack thereof) of gratuitous name-dropping. To get notified when we post it → join our email list.

![]()

This post was written by Zachary Crockett. You can follow him on Twitter here.