![]()

In 17th-century Colonial America, there was no shortage of morality laws. As early European settlers formed colonies in modern-day America’s Eastern-most states, Puritan leaders made sure to administer their docket of strict religious rules on everyone around them.

At the same time, these early settlers had almost no understanding of science, and the “supernatural” was considered to be a part of everyday life. The lack of understanding of natural phenomena combined with a puritanical and capricious legal system resulted in some horrible miscarriages of justice: citizens were burned at the stake for engaging in “witchcraft,” stoned for exhibiting “satanic” traits, and, most improbably, hanged for supposedly copulating with and impregnating animals.

The last of these crimes, “buggery,” or the act of engaging in lewd sexual conduct with an animal, was considered the most reprehensible; the vast majority of the time, sentences were handed down with little or no evidence of guilt. Digging through early records of Colonial America yields multiple cases of men being executed for merely resembling barn animals — because if an animal resembled a man, it therefore implicated him as its father.

These mens’ stories serve as a good (if not disturbing) reminder that in the absence of a well-functioning legal system, people have been routinely put to death over the most absurd allegations imaginable.

***

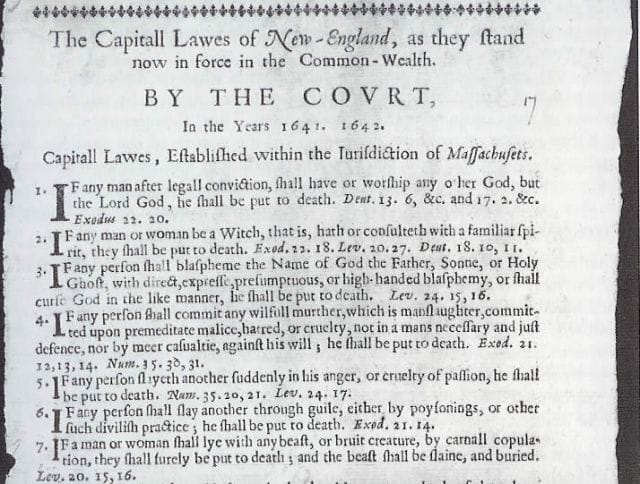

The Puritan “legal” code essentially followed the Old Testament Bible word for word: anything deemed to be sinful in the text was appropriately punished in the New England colonies. Among the many crimes one could commit in the colonies, “buggery” was thought to be the most vile — so much so, that Plymouth’s Governor, William Bradford, once declared the act “too fearful to name.”

Both in the Bible and in Puritan legal codes, buggery was treated as a gravely serious offense, and almost always resulted in death for the accused.

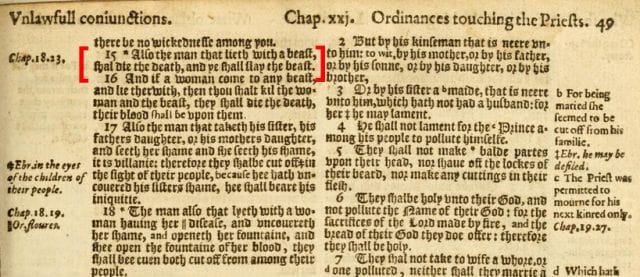

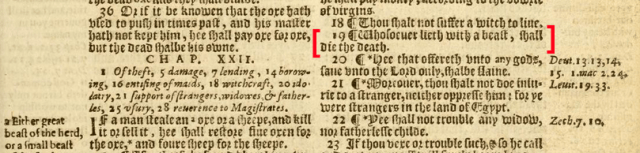

For those who had sex with animals, the Old Testament was especially unforgiving. Exodus 22:19 declares that “Whosoever lieth with a beast shall surely be put to death;” similarly, Leviticus 20:15 states, “[If] a man lie with a beast, he shall surely be put to death: and ye shall slay the beast.” In 17th century America’s courts, these words were interpreted quite literally

Leviticus 20:15 and Exodus 22:19 both pronounce that a man should be put to death for copulating with an animal; screenshots from a 1606 copy of the Old Testament, similar to that favored by New England’s Puritans

The first recorded case of a settler being punished for buggery in New England was that of William Hackett, a Plymouth, Massachusetts man. Hackett, who was estimated by the court to be 20 years old, was spotted by an ill woman, while allegedly “[engaging] in buggery with a cow.” To make matters worse, she claimed he’d done so while the rest of town was in a Sunday church service. Needless to say, the court was not forgiving of Hackett’s action: though he insisted he’d merely attempted the act, and despite there being only one, highly questionable witness, he was found thoroughly guilty. The following day, the cow was brought before Hackett and slaughtered, and then Hackett himself was hung from the gallows.

According to the historical records of the New Haven, Connecticut colony, another man was convicted of buggery just a few months later — and this occurrence was much stranger. George Spencer was a lowly servant, who worked long days tending to his master’s stock. Much to Spencer’s misfortune, one of the cows birthed a disfigured sow — “a prodigious monster” — that apparently bore a great semblance to him. Like Spencer, the fetus “[had] butt one eye for use…the other [was] whitish and deformed.” For local Puritan townsfolk, only one conclusion could be drawn: Spencer had copulated with the cow, and the sow was his offspring.

In court, his history of “lying, scoffing, and lewd spirit” was brought to light as “corroborating” evidence, and though Spencer denied his guilt, he was sent to prison. Here, Puritan magistrates convinced him that, unless he confessed to his sin, he’d eternally burn in hell; after some time, he admitted that he’d lusted for the animal. Though lacking any witness testimony, and possessing no evidence of Spencer’s crime, the court pronounced that it was “aboudnantly satisfied in the evidence,” and, in accordance with New England’s capital laws, no time was spared in putting the man to death.

The capital laws of New England, including buggery (#7); full list here

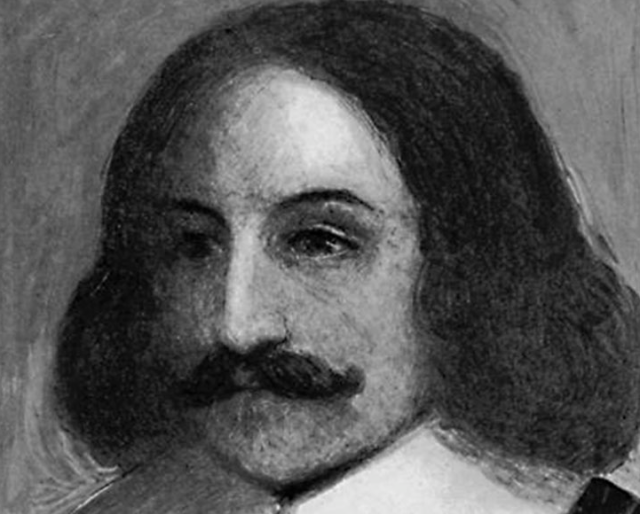

The following year, back in Plymouth, a 17-year-old servant named Thomas Granger was accused of the most heinous act of buggery yet. Plymouth’s Governor, William Bradford, found the case such a “sad spectakle” that he devoted an entire page to it in his diary of 1642:

“Thomas Granger…was this year detected of buggery (and indicted for the same) with a mare, a cow, two goats, five sheep, 2 calves, and a turkey. Horrible it is to mention, but the truth of the historie requires it. He was first discovered by one that accidentally saw his lewd practise towards the mare. (I forbear perticulers.) Being upon it examined and committed, in the end he not only confest the fact with that beast at that time, but sundrie times before, and at severall times with all the rest of the forenamed in his indictmente…”

Following Granger’s confession, various sheep were rounded up, and he was forced to identify his muses. After he’d done so, the incriminated creatures were slaughtered before his eyes — “first the mare, and then the cow” — before Granger himself was hanged. His execution marked the first recorded instance that a juvenile was put to death in America.

Plymouth’s Governor, William Bradford, came down especially hard on those who took “beasts as mistresses”

Five years later, back in the New Haven Colony, the strangest case of buggery in history unfolded — that of aptly-named Thomas Hogg, a man accused of sexually engaging a pig.

Like the aforementioned George Spencer, Thomas Hogg was a servant who often worked with his master’s animals. According to the official Records of Colony and Plantation of New Haven (1638-49), when a sow was born with “faire white skinne and head [and] one eye like his, the bigger on the right side,” the apparently similar-looking Hogg was implicated as the animal’s lover.

A series of unrelated witnesses came forward, attesting to Hogg’s “indecency” — first, a woman who claimed to have seen him “act “with filthiness with his hands by the fire side,” and then another who’d supposedly seen Hogg’s “members.” Though Hogg claimed his “belly was broake,” requiring him to wear especially loose trousers, the court took favor with the witness’ testimonies, and his predisposition for animals was put to the test.

With the Governor and court officials at his side, Hogg was brought to a barnyard, where he was presented with his “mistress” — the sow that bore his likeness. He was then forced to “scratt” (fondle) the animal, to see if it produced any favorable reaction. Unfortunately for Hogg, “there immedyatley appeared a working of lust in the sow, insomuch that she prowed out seede before them.”

Of course, this test could not be held as hard evidence without a control group: another sow was brought before Hogg, and when it was “not moved at all” by the man’s advances, he was found guilty of buggery.

Despite his charges, Hogg seems to have miraculously avoided capital punishment. Written records show that he was alternatively whipped and imprisoned in a hard labor camp, where his “lusts [could] not be fedd.”

***

Hogg’s case was indicative of the changing nature of capital punishment in Colonial America: by the end of the 17th century, cases of buggery less frequently resulted in death. Moving forward, many of the accused were merely branded on the forehead, publicly humiliated, and permanently expelled from the colonies. In the time of Puritans, this was considered progressive.

As the state became more secularized and strict morality codes loosened, the Puritans’ harsh punishments for sexual “crimes” — including buggery — were forgotten. But for a period of time in American history, men were executed for nothing more than bearing a resemblance to barn animals.

![]()

This post was written by Zachary Crockett; you can follow him on Twitter here.

To get occasional notifications when we write blog posts, please sign up for our email list.