“Tonight, I will make you the greatest wingman in the history of wingmen.”

— Barney Stinson, How I Met Your Mother

![]()

Go to any bar on a Friday night, and you’ll see the “wingman” in his natural habitat. He’ll confer with his comrade and scan the room before embarking into an abyss of lonely females. His mission? To persuade the ladies that his friend — however unappealing — is a charming composite of Ryan Gosling and Michelangelo’s David.

Film and television have immortalized wingmen — both the highly successful (Barney Stinson in How I Met Your Mother, Vince Vaughn in Swingers), and the less-than-skilled (Pedro in Napoleon Dynamite) — as heroic martyrs of the bro-kind. “A good wingman’s generosity knows no bounds,” AskMen proclaims, “and he will do whatever is necessary to make sure his No. 1 gets a shot with the girl.”

And winging isn’t sex-exclusive — women similarly employ friends in courting situations (though most of the time, for much different reasons), and each delineates her own set of theories — steeped in years of field research — as to how the proper wing-woman should act.

But is there truth to the harried role of the “winger”? Are friends truly willing to sacrifice their dignity and morals to get you into the arms of your muse? Is wing-manning steeped in the very nature of our evolutionary make-up? We’ve compiled a selection of scientific studies to address these questions (and others) — some of which may come as a surprise.

The Barney Stinson Principle

It is commonly espoused that, above all else, a good wingman is a masterful liar.

Jennifer Argo, a professor at Alberta’s School of Business, wondered whether this held definitive, scientific truth. In 2012, with a team of researchers, she published a paper in the Journal of Applied Social Psychology informally titled “The Barney Stinson Principle” (after How I Met Your Mother’s serial philanderer and go-to wingman, who often lies to his friend Ted’s benefit). The study found that, when confronted in a social situation, people are willing to enhance (or outright fabricate) the reputation of their friends to help them save face.

Argo’s findings indicate that, like Barney, the wingman is “primed to step in with strategic identity support.”

In the study, 95 undergraduate students were presented a scenario in which a friend tells them about the new car he just purchased for $20,000; another person walks in and declares to have purchased the exact same vehicle for $18,000. The test participant is then asked to answer a question: if a third person were to walk in, what price would you tell her your friend paid for the car? Would you lie to cover up the fact that he got swindled?

While Argo is hesitant to reveal the numeric results of her study (which is published in a paywalled publication), she says the “vast majority” of respondents would, with little hesitation, sacrifice their moral fiber to make a friend look good. Argo adds that these results are easily translatable to a suiting context, in which a wingman must decide whether or not to decorate his bro’s persona:

“Based on the findings, it would seem reasonable to expect that people who understand their friends should be willing to step in as a wingman in a number of different contexts if their friends are in need.”

A follow-up study, however, clarified that this behavior was contingent on the aforementioned friend being physically present in the room. A friend’s hypothetical presence, found Argo, made participants more empathetic toward his plight; empathy, in turn, made them more likely to twist the truth. “This is an instance when you don’t have the opportunity to make yourself look good, so somebody else does it for you,” Argo clarifies. “But you’re better off to hang out with your friends (in these situations) because your friends will look out for you.”

Wingwomen vs. Wingmen

In the 2009 study Cooperative Courtship: Helping Friends Raise and Raze Relationship Barriers, Joshua Ackerman (MIT) and Douglas Kenrick (Arizona State University) investigate the “patterns of cooperation within courtship interactions.” For decades, they assert, mate selection research focused predominantly on competition, and failed to point out the “team sport” nature of courting. They set out to systematically prove the prevalence of the wingman.

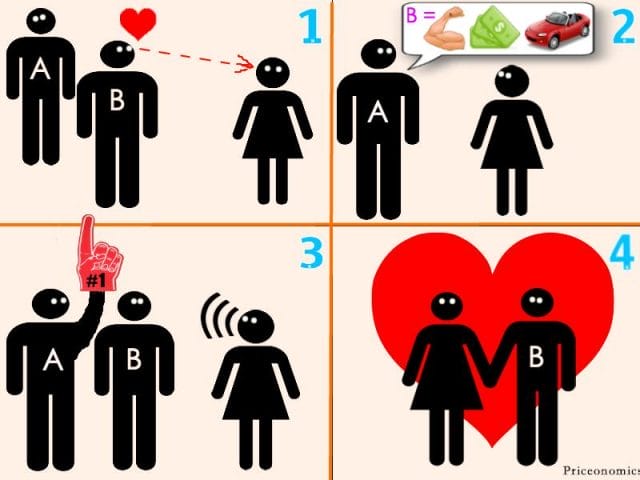

Forty-eight students were asked to generate a variety of ways people might assist others in flirtatious encounters; subsequently, the most common methods were curated and rated in likelihood by 200 additional participants, following a set of instructions:

“The cartoons below involve flirtatious situations. Each cartoon should be read left to right. The circles represent people, and those circles sharing a letter are friends (not sexual partners). Dotted lines represent people looking in the direction of the arrow.”

NOTE: Scene 1 = an avoidance strategy; Scene 2 = an access strategy; Scene 3 = a combination of avoidance and acceptance strategies. Source: MIT

Overwhelmingly, participants recognized the first scenario (avoidance) as intrinsically female (A=male, B=female); likewise, the second situation was perceived as intrinsically male (B=male, A=female). The situation in schematic #3 was perceived to be mutually beneficial.

The scientists’ findings probably won’t surprise harried veterans of the bar scene: women are more likely than men to cooperate during courtship — but they cooperate to avoid “targets” in which they have “no romantic interest.” Conversely, men cooperate to “break down romantic barriers” by having a friend partner up with a female target’s less-attractive counterpart (ie. “taking one for the team”). Men, on a whole, were nearly 150% more likely to interact with a female when flanked by friends than when flying solo.

Why do females cooperate to reject potential suitors? Ackerman and Kenrick site the “parental investment theory,” which stresses the “minimum obligatory investment each sex must make” to conceive offspring. In reproduction, most females species (including humans) must expend more “physical and temporal resources” than males, whereas males are “primarily limited by their ability to achieve sexual access to females.”

“At a theoretical minimum,” writes Ackerman, “males need only devote enough time and energy for sexual intercourse; any single mating act holds a higher potential cost for a female than a male.” To manage this cost, females are more selective with potential mates — particularly those of the “short-term” variety. Women collectively recognize this and are willing to step in to help a friend avoid these “costs.”

Primal Roots

If all of this sounds animalistic, that’s because it is. The wingman is not a human construct: it’s a practice rooted in millions of years of evolutionary biology.

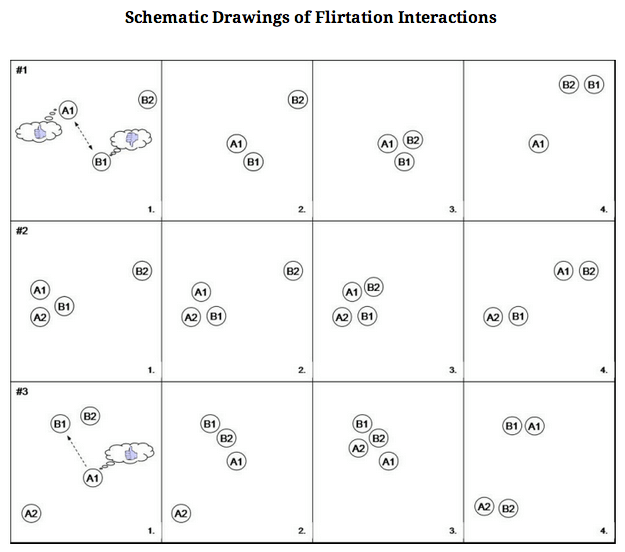

In his paper Cooperative Courtship in Wild Turkeys, Alan Krakauer clarifies that wild male turkeys are the ultimate “wingbirds.” Turkeys, Krakauer finds, “form coalitions of two to four same-aged males” that court females — but only one of these males is dominant; the others are “subordinates” who serve the sole, intentional purpose of making the dominant look good. The courting routine plays out in a similar nature to that of humans: the dominant male’s wingman approaches a female target and flashes his brilliant, colorful plumage to chase away competitors, while the dominant (reproductively successful) male performs a “strutting dance” to seal the deal.

Like a wingman, the “subordinate” turkey flamboyantly displays himself to attract a mate, but only does so for the benefit his friend. Over the course of a mating season, the subordinate turkey’s loyalty goes unrewarded: on average, he helps his dominant friend haul in 14 mates; he, on the other hand, nets zero. But his efforts as a wingman nearly double his dominant friend’s success rate over that of “solo” turkeys, who go without wingmen.

Dominant = turkey with wingman; Subordinate = turkey wingman; Solo = turkey without wingman. Source: UC Davis

Turkeys aren’t alone in their wingman rituals. Male lions routinely form coalitions to approach prides of lionesses. In a 1982 study, scientists at the Allee Laboratory of Animal Behavior found that 42% of male lions enlisted the help of a non-familial friend to help them attract the attention of a young Nala — and their success rates, like turkeys’, were much higher for doing so.

Primates commonly enlist wingmen too: male howler monkeys collaborate to create mating opportunities, and male chimps work together to both attract and guard mates for “friends.” Female bonobos utilize wingwomen, but, like human females, more commonly use these alliances to “reduce male sexual coercion” than to attract it.

![]()

Animals are also scientifically proven to make great wingmen for humans. Dognition conducted a study earlier this year that found 82% of people were more likely to approach an attractive member of the opposite sex with their dog present.

Dogs don’t just make it easier for men to approach women — they drastically increase a man’s “success” rate. In another study carried out by France’s University of Bretagne Sud, a Frenchman named “Antoine” approached 240 women using the same pick-up line — half of the time with his dog, and half of the time without his dog:

“Hello. My name’s Antoine. I just want to say that I think you’re really pretty. I have to go to work this afternoon, but I was wondering if you would give me your phone number. I’ll phone you later and we can have a drink together someplace.”

Without his dog, Antoine’s mediocre pitch secured him only one in ten phone numbers. With the dog, his success rate leapt, astonishingly, to one in three. The researchers explained that Antoine’s dog — a “lovable black mutt with undeniable charisma” — was perceived to be a reflection of his own personality, as well as an “active beacon” of his ability to care for a creature. In essence, Antoine’s dog got him laid — and at a handsome rate.

Concluding Thoughts

These findings have clarified several truths: we lie to make our friends look better, we utilize cooperative courting techniques to “break barriers” (or, if you’re a female, to put them up), and, most importantly, our dating rituals are no more advanced than those of wild turkeys.

But a question lingers: how effective is wing-manning? Similar courtship patterns exhibited by animals suggest tangible returns on a genetic level; does this success translate into the human realm?

Thomas Edwards is a professional wingman and operates his own wingman-for-hire business. While he maintains he’s “not in the business of getting people laid,” Edwards says his services have the potential to be a life-changing experience for men who lack a partner in crime. One client raves about his success with the wingman:

“With Thomas as my professional wingman…I have twice the confidence that I had five months ago. While I always had the nerves to approach a woman, it was usually an awkward conversation, like riding the mechanical bull at a bar; how long can you hold on? Thomas showed me not only how to hold one woman’s interest, but also the interest of her friends.”

But then again, if most wingmen were so successful, services like this wouldn’t exist in the first place.

This post was written by Zachary Crockett. Follow him on Twitter here, or Google Plus here.