Several months ago, this author sat at a classical music concert, trying to convince himself that wine is not bullshit.

That may seem like a strange thought to have while listening to Beethoven’s Symphony No. 7 in A major. But Priceonomics had recently posted an article investigating The Price of Wine, part of which reviewed research that cast doubt on both consumers’ and wine experts’ ability to distinguish between quality wine and table wine or identify different wines and their flavors. It seemed a slippery slope to the conclusion that wine culture is nothing more than actors performing a snobbish play.

Listening to an accomplished musician while lacking any musical experience resulted in a feeling familiar to casual wine drinkers imbibing an expensive bottle: Feeling somewhat ambivalent and wondering whether you are convincing yourself that you enjoy it so as not to appear uncultured.

Given the inexplicable, unintuitive conclusions of this research on wine, thinking about classical music promised firm ground to stand on. Despite the influence of class on classical music consumption and the fact that outsiders do not necessarily recognize and enjoy great music performances, no one believes that Beethoven and their 10 year old cousin play the piano equally well. Surely in just the same way a $2,000 bottle of wine and a $5 bottle are not indistinguishable?

This past week, however, Priceonomics reviewed research that cast similar doubt on our ability to appreciate great performances of classical music.

As we wrote in a more recent post, wine is not bullshit. But the reason that research can seemingly suggest that our enjoyment of wine, certain foods, and classical music is BS can tell us a lot about snobbery and how we experience the finer things in life, the limitations of expert judgment in any field, and why marketing is so powerful.

Watching Not Hearing

Chia-Jung Tsay was an extremely talented young pianist. She performed at Carnegie Hall at age 16, attended prestigious conservatories, and competed in music competitions. But her success seemed inconsistent. During auditions, she noticed that she did better when she performed live or provided a video than when she submitted an audio recording.

Tsay could have harbored dark suspicions about the judges for the rest of her life. But today she is also a talented psychologist and an Assistant Professor in Management Science and Innovation at University College London, so she set up an experiment to examine the role of visual cues in judging musical performances.

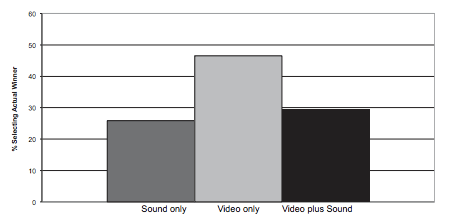

Tsay took the actual audition recordings of the top 3 finalists from 10 prestigious international classical music competitions and asked a group of participants to select the winners. One group watched a video audition, the second group listened to an audio recording of the same audition, and a final group watched the video audition with the sound turned off.

As her study participants were untrained in classical music, Tsay expected them to do no better at choosing a winner than random chance. This proved true for the first two groups, who chose the winner less than 33% of the time. But to everyone’s surprise, the amateurs did significantly better than chance when watching only a silent video.

Source: PNAS

Source: PNAS

Tsay then replicated the experiment with professional musicians and found the same results. Despite their expertise, the musicians also did no better than chance at picking the winner based on audio or video recordings. But when they watched a silent video recording, they too performed dramatically better.

Source: PNAS

Expert judges and amateurs alike claim to judge classical musicians based on sound. But Tsay’s research suggests that the original judges, despite their experience and expertise, judged the competition (which they heard and watched live) based on visual information just as amateurs do.

Looking Not Tasting

The key to understanding the aforementioned wine research – without concluding that the entire wine industry is a massive conspiracy powered by snobbery to sell identical fermented grape juice – is that just like with classical music, we do not appraise wine in the way that we expect.

In a follow up to our article on the price of wine, Priceonomics revisited this seemingly damning research: the lack of correlation between wine enjoyment and price in blind tastings, the oenology students tricked by red food dye into describing a white wine like a red, a distribution of medals at tastings equivalent to what one would expect from pure chance, the grand crus described like cheap wines and vice-versa when the bottles are switched.

The research is popular, cited regularly in blog posts and articles that either call wine tasting fraudulent or (more commonly) conclude that when it comes to the enjoyment of wine, price tags and perceived prestige trump the physical product.

To get a grasp on what this means, we related how we see the same confusion with food.

Taste does not simply equal your taste buds – it draws on information from all our senses as well as context. As a result, food is susceptible to the same trickery as wine. Adding yellow food dye to vanilla pudding leads people to experience a lemony taste; diners eating in the dark at a chic concept restaurant confuse veal for tuna; branding, packaging, and price tags are equally important to enjoyment; and cheap fish is routinely passed off as its pricier cousins at seafood and sushi restaurants.

Just like with wine and classical music, we often judge food based on very different criteria than what we claim. The result is that our perceptions are easily skewed in ways we don’t anticipate.

Judging in a Blink

It’s unclear what we should take away from these observations. What does it mean for wine that presentation so easily trumps the quality imbued by being grown on premium Napa land or years of fruitful aging? Is it comforting that the same phenomenon is found in food and classical music, or is it a strike against the authenticity of our enjoyment of them as well? How common must these manipulations be until we concede that the influence of the price tag of a bottle of wine or the visual appearance of a pianist is not a trick but actually part of the quality?

To answer these questions, we need to investigate the underlying mechanism that leads us to judge wine, food, and music by criteria other than what we claim to value. And that mechanism seems to be the quick, intuitive judgments our minds unconsciously make.

In a famous experiment, psychologist Nalini Ambadyprovided participants in an academic study with 30 second silent video clips of a college professor teaching a class and asked them to rate the effectiveness of the professor. When she compared the ratings to the end of semester ratings of real students, she found her participants had done astoundingly well at rating the professor off an initial impression – there was an extremely strong correlation of 0.76. Participants were just as effective when watching 6 second video clips and when comparing their ratings to ratings of teacher effectiveness as measured by actual student test performance.

The power of intuitive first impressions has been demonstrated in a variety of other contexts. One experiment found that people predicted the outcome of political elections remarkably well based on silent 10 second video clips of debates – significantly outperforming political pundits and predictions made based on economic indicators. Chia-Jung Tsay’s analysis of classical musician auditions explicitly drew on this idea by providing participants with clips of each performance ranging from 1 second to 1 minute.

In a real world case, a number of art experts successfully identified a 6th century Greek statue as a fraud. Although the statue had survived a 14 month investigation by a respected museum that included the probings of a geologist, they instantly recognized something was off. They just couldn’t explain how they knew.

Cases like this represent the canon behind the idea of the “adaptive unconscious,” a concept made famous by journalist Malcolm Gladwell in his book Blink. The basic idea is that we constantly, quickly, and unconsciously do the equivalent of judging a book by its cover. After all, a cover provides a lot of relevant information in a world in which we don’t have time to read every page.

Gladwell describes the adaptive unconscious as “a kind of giant computer that quickly and quietly processes a lot of the data we need in order to keep functioning as human beings.” He quotes psychologist Timothy D. Wilson:

“The mind operates most efficiently by relegating a good deal of high-level, sophisticated thinking to the unconscious, just as a modern jetliner is able to fly on automatic pilot with little or no input from the human, ‘conscious’ pilot. The adaptive unconscious does an excellent job of sizing up the world, warning people of danger, setting goals, and initiating action in a sophisticated and efficient manner.”

Our internal computers are powerful but unknowable. They can size up someone’s personality or skill at an occupation in seconds, but we can rarely articulate the basis of our judgments. The desired characteristics in a partner listed by speed daters, for example, rarely match the personalities of the person they connect with.

But this unknowability also makes it easy to be led astray when our intuition makes a mistake. We may often be able to count on the price tag or packaging of food and wine for accurate information about quality. But as we believe that we’re judging based on just the product, we fail to recognize when presentation manipulates our snap judgments.

In follow up experiments, Chia-Jung Tsay found that those judging musicians’ auditions based on visual cues were not giving preference to attractive performers. Rather, they seemed to look for visual signs of relevant characteristics like passion, creativity, and uniqueness. Seeing signs of passion is valuable information. But in differentiating between elite performers, it gives an edge to someone who looks passionate over someone whose play is passionate.

Outside of these more eccentric examples, it’s our reliance on quick judgments, and ignorance of their workings, that cause people to act on ugly, unconscious biases – judging men to be better workers and managers than women, for example, or profiling minorities in police work.

It’s also why – from a business perspective – packaging and presentation is just as important as the good or service on offer. Why marketing is just as important as product.

On Experts

So are we able to overcome the faults of our intuitions? Or are we forever susceptible to the manipulations of marketers, even in the enjoyment of the things we love and care about most?

Despite describing the dark side of these snap judgments, Malcolm Gladwell ends Blink optimistically. By paying closer attention to our powers of rapid cognition, he argues, we can avoid its pitfalls and harness its powers. We can blindly audition musicians behind a screen, look at a piece of art devoid of other context, and pay particular attention to possible unconscious bias in our performance reports.

Gladwell describes experts who have the training to examine the powerful computations made by their adaptive unconscious. Whereas laymen will likely judge the condiment in the noblest packaging to taste the best, food tasters analyze mayonnaise according to multiple dimensions of appearance, texture, flavor, and chemical-feeling factors. Tacking a gold ribbon on the bottle won’t fool them.

But Gladwell’s success in demonstrating how the many calculations our adaptive unconscious performs without our awareness undermines his hopeful message of consciously harnessing its power. Gladwell describes a top tennis coach named Vic Braden who had a talent for knowing when a star player was about to blow a serve and double-fault. In the time between the player tossing the ball and making contact with it, Braden just knew. He had no idea why, but his intuition somehow recognized the pattern of a bad serve.

As a former world-class tennis player and coach of over 50 years, Braden is a perfect example of the ideas behind thin slicing. But if he can’t figure out what his unconscious is up to when he recognizes double faults, why should anyone else expect to be up to the task?

Let’s return to wine tasting. A critic/troller of our previous wine post points out that the wine industry fully understands the limitations of blind tastings and wine competitions and that it usually treats them as marketing fodder rather than flawless analyses of wine quality.

Still, when a group of experts judged a collection of French and American wines in the Judgment of Paris, one judge picked up a Californian wine, tasted it, and said “Ahh, back to France.” He then picked up a French bordeaux, sniffed, and said, “That is definitely California. It has no nose.” The recent Judgment of Princeton that pitted French wines against New Jersey wines came out essentially as a draw.

Outcomes like these don’t mean that all wine is the same or that France’s best wines aren’t generally better than New Jersey’s choice selection. (We emphasize this given all the misinterpretation of our last blog post on wine.) But it does suggest that our reliance on cues and context can seriously trump expertise.

Oenophiles don’t exactly search out opportunities to look foolish at their hobby or job – regardless of whether they are snobs – so we don’t expect to see an exhaustive analysis that empirically demonstrates what level of training equates which degree of mastery over blind tastings, switched bottles, and marketing tricks. One group that can identify glasses of wine with astonishing frequency – down to the year and vintage – is Master Sommeliers. Thanks to the new documentary Somm, their story is transparent to laypeople. Their training consists of years of obsessive study and practice.

Confusing a French wine with a New Jersey wine may embarrass a self-professed wine expert, but flawed judgment in fields like medicine and investing has more serious consequences. The fact that expertise is so tricky leads psychologist Daniel Kahneman to assert that most experts should seek the assistance of statistics and algorithms in making decisions.

In his book Thinking, Fast and Slow, he describes our two modes of thought: System 1, like the adaptive unconscious, is our “fast, instinctive, and emotional” intuition. System 2 is our “slower, more deliberative, and more logical” conscious thought. Kahneman believes that we often leave decisions up to System 1 and generally place far “too much confidence in human judgment” due to the pitfalls of our intuition described above.

In an interview on the subject Kahneman said:

I’m not claiming that the predictions of experts are fundamentally worthless. … Take doctors. They’re often excellent when it comes to short-term predictions. But they’re often quite poor in predicting how a patient will be doing in five or 10 years. And they don’t know the difference. That’s the key.

Not every judgment will be made in a field that is stable and regular enough for an algorithm to help us make judgments or predictions. But in those cases, he notes, “Hundreds of studies have shown that wherever we have sufficient information to build a model, it will perform better than most people.”

We can see the insight of models and algorithms in the example of marital therapy from Blink. Despite their experience and training, marital therapists are just as bad as ordinary people at predicting whether a couple will divorce based on one meeting. Unsurprisingly, it’s too complicated for even our powerful intuitions.

One exception is therapist and researcher John Gottman, who can predict with roughly 90% accuracy whether a couple will stay married based on a 15 minute observation session. Due to years of recording marriage sessions and developing encoding systems to recognize the most salient factors in troubled marriages, Gottman’s formulas are extremely accurate at making this prediction and his intuition not bad either. He’s learned to look for the “Four Horseman” of a doomed marriage: defensiveness, stonewalling, criticism and contempt. (Contempt is the worse.)

Paul Graham has the right to call himself an expert in investing in early stage startups. As co-founder of Y-Combinator, he has invested in hundreds of startups and interviewed thousands of entrepreneurs. Yet he decided several years ago to tape his interviews and analyze the findings. Among the insights, it revealed an interesting pitfall in Graham’s intuition. In his words:

“I can be tricked by anyone who looks like Mark Zuckerberg. There was a guy once who we funded who was terrible. I said: ‘How could he be bad? He looks like Zuckerberg!’ ”

In a similar example in medicine, a recent study revealed that “Thousands of women are dying from strokes as doctors are missing crucial signs of heart problems because many patients were too well-groomed and looked healthy.”

Experts can avoid the pitfalls of intuition more easily than laypeople. But they need help too, especially as our collective confidence in expertise leads us to overconfidence in their judgments.

When the Trick is the Game

Everyone recognizes the phenomenon described in this article. People dress up for job interviews even when looks should have no effect on performance. Marketers go about their work. Couples bring out the nice china for dinner parties.

But no one has fully internalized these lessons. Articles on this wine research recommend that serving cheap wine in fancy bottles or reaching for bottom shelf wine. Does that mean you should constantly deceive yourself into enjoying cheap wine? Or never spend more than $10 since we often mistake $10 bottles with $100 bottles? In that case, will you never spend over $10 on sushi for same reason? Or never spend over $30 at a fancy restaurant because the ambiance often tricks people into thinking a simple chicken dish is fancy?

Ordinary consumers don’t think hard and deliberately when sipping wine over a conversation with friends or listening to a concert. Even when thinking deliberatively, overcoming our intuitive impressions is difficult for experts and amateurs alike. This article has referred to the influence of price tags and context on products and experiences like wine and classical music concerts as tricks that skew our perception. But maybe we should consider them a real, actual part of the quality.

Losing ourselves in a universe of relativism, however, will lead us to miss out on anything new or unique. Take the example of the song “Hey Ya!” by Outkast. When the music industry heard it, they felt sure it would be a hit. When it premiered on the radio, however, listeners changed the channel. The song sounded too dissimilar from songs people liked, so they responded negatively.

It took time for people to get familiar with the song and realize that they enjoyed it. Eventually “Hey Ya!” became the hit of the summer. The same is true of the Aeron chair. Its designer intended for the chair to be the most ergonomically correct office chair possible – the ultimate in comfort. But consumers associated comfort with big, padded armchairs. The Aeron, in Malcolm Gladwell’s words, was a slender chair that looked like “the exoskeleton of some prehistoric insect.” It didn’t look like a comfortable chair, so early consumers rated the chair poorly on comfort. But eventually they realized that the chair was really comfortable despite not looking it, and now companies spend $500 bucks a pop to stock their office with Aeron chairs.

What does this all say about wine snobs? The answer is just as unclear. Due to the way that appreciation of wine, fancy food, and other aspects of high culture is often used to police class lines, studies demonstrating the limitations of expert judgment in these areas become fodder for class warfare and takedowns of wine snobs.

That’s fair. Many boorish people talking about the ethereal qualities of great wine probably can’t even identify cork taint because their impressions are dominated by the price tag and the wine label. But the classic defense of wine – that you need to study it to appreciate it – is also vindicated. The open question – which is both editorial and empiric – is what it means for the industry that constant vigilance and substantial study is needed to dependably appreciate wine for the product quality alone. But the question is relevant to the enjoyment of many other products and experiences that we enjoy in life.

Our intuition leads us astray in situations ranging from enjoying a meal to diagnosing medical diseases. Maybe the most important conclusion is to not only recognize the fallibility of our judgments and impressions, but to recognize when it matters, and when it doesn’t.

This post was written by Alex Mayyasi. Follow him on Twitter here or Google Plus. To get occasional notifications when we write blog posts, sign up for our email list.

Update: A previous version of this post stated that Dr. Tsay’s audition clips were only 6 seconds long. She actually looked at clips ranging from 1 second to 1 minute. The post has been updated to reflect this.