Thirty-five years ago, Robert Nelson stepped onto a small platform in the unlit courtyard of a San Francisco pier, raised his arms to the fog, and began to juggle. It was muggy and dark, and few were there to witness the show. In its infant stages, Pier 39 and had yet to develop into a tourist metropolis. But Nelson, The Butterfly Man, seemed content merely pursuing his artistic visions as a street performer.

Street performing was in vogue long before The Butterfly Man. In a 1718 memoir, Ben Franklin recalls reciting “grub-street ballad[s]” in the cobbled pathways of Boston for change. Years later, in 1860, Nathaniel Hawthorne commented on the unsung value of of a local street performer:

“It seems strange…that she should throw away her melody in the streets for the mere chance of a penny, when sounds not a hundredth part so sweet are worth from other lips purses of gold.”

But it wasn’t until the late 1960’s that performers began to make names for themselves on the streets of San Francisco. Shields and Yarnell, the dynamic mime duo, got their start in Union Square in 1970 before performing on Late Night With Johnny Carson and becoming world-famous. Ray Jason, widely regarded as the first street juggler in San Francisco, recalls his meager lifestyle in early years:

“Getting started, I lived in a lot of places in the city, in my truck for quite a while and in poorer sections of North Beach and the Tenderloin. When you’re a juggler, you take what you can get.”

Around this time, Norbert “Dynamite” Yancey began singing rhyming ballads to passersby in front of Ghirardelli Square. Today, a board of newspaper clippings by his side exhibits snapshots of his life: meeting Gorbachev in Poland, playing with the likes of Santana and Pavarotti. He sings songs in over 20 languages and has traveled the world, but still returns to his “pitch,” or performance spot, to serenade tourists on the street.

Norbert Yancey (twentyfouratheart)

Then, of course, there is the World Famous Bushman. A 30-year fixture near Joe’s Crab Shack on Jefferson Street, he earns his living jumping out from behind a bush and “OOGA-BOOGA”-ing tourists and unsuspecting passersby. On any given weekday, he can be found perched behind his hand-crafted foliage, waiting to scare unsuspecting victims.

These characters paved the way for street performance in San Francisco. Today, they are regarded as celebrated cultural icons, synonymous with the city itself.

These select few have achieved formidable success: the iconic Bushman claims to rake in $60,000 per year and lives comfortably in a one-bedroom apartment downtown. But how sustainable is the life of an average street performer? Are tips and merchandise sales enough to scoot by in one of the most expensive cities in the world?

Performer Rights in San Francisco: A Brief History

The first issue that bedevils street performs is legislative: whether their presence is even legal.

From 1970 to 2010, there have been 15 major court cases disputed over public performance rights and regulations. Almost all have ended favorably for performers, with artistic rights upheld under the First Amendment. But as Bob Davis of the San Francisco Entertainment Commission clarifies, “There is a First Amendment right to free speech but it comes with caveats and they are primarily focused around public safety and sound.”

These “caveats” mainly come in the form of three citations for San Francisco performers: blocking the sidewalk (MPC 63a), amplification without a permit (MPC 43a), and vending without a permit (MPC 869, the same citation given to ticket scalpers at the ballpark). Each carries a $50-$250 fine, per city code.

One local performer recalls a run-in with police, “I explained to him that we have just as much right to occupy space and sell our art as any street artist does, but he did not want to hear it.” He then explains the magnitude of citations doled out along Fisherman’s Wharf:

“These latest harassment tickets boost the grand total to over 100 bogus tickets issued in the past 3 years, almost all by one officer. This represents over 1000 hours of punitive time spent by recipients in the process of clearing up these “infractions”. This does not even take into account the time wasted by the various legal departments tracking and recording these tickets.”

In 2004, Bushman was cleared of four misdemeanor charges, all of which stemmed from the 240 citations he accrued during his 35 years on the street. While most have been completely dismissed, the citations, which each require multiple court appearances, have pulled him from his usual haunt in front of Joe’s Crab Shack.

Fisherman’s Wharf and the Permit Paradox

So, why don’t performers acquire the appropriate permits to defend themselves from this onslaught of citations?

While New York and other major cities have clear permit systems in place for buskers, there is something of a catch-22 for performers in San Francisco: they are often cited for lacking permits that don’t exist.

Under San Francisco’s legal code, artists and performers are defined differently. An artist is a person who sells the work of a learned craft (i.e. “bead making, candles, glass art, woodwork, printmaking”). A performer is “an individual or group who provides public entertainment and self-expression,”including “musicians, mimes, magicians, jugglers, human statues, dancers…and any other activity protected by the First Amendment.”

Until recently, only “artists” had the legal protection of city-issued permits. In 1972, the San Francisco Commission for the Arts created the Street Artists Program to encourage and protect the city’s renegade artisans. Now, for a yearly permit fee of $679 (2013), artists can legally set up sidewalk shops in designated 4×4 allotments scattered through the city. Currently, more than 400 artists enjoy this privilege.

However, the Commission for the Arts offers no alternative for performers. In fact, the program’s handbook dedicates an entire provision to state that performers are not, and will never be, eligible for these permits. Following this provision is the Horatio Alger-esque tale of a female street artist who used the program’s ample resources to “operate a $6 million clothing company by 1994.”

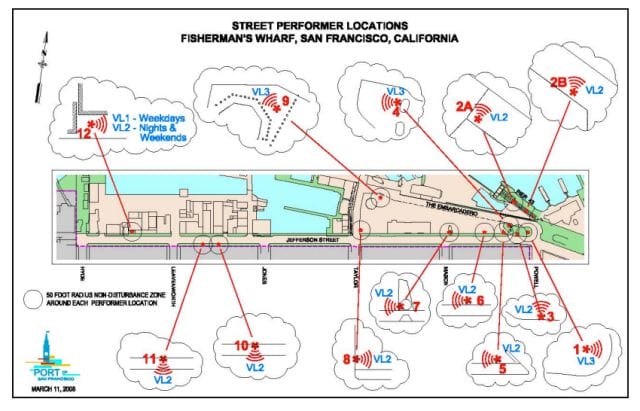

In 2007, performers along the wharf revelled in a small miracle. Stephen Dreyfuss, a Berklee School of Music graduate and San Francisco street performer since 1987, trudged his way through nearly five years of legislative sludge to create the Fisherman’s Wharf Street Performer Program — the first performer permit program in city history. With its creation, wharf performers can obtain permits ($500/year, or $50/month) to perform in 12 sanctioned spots along Jefferson Street, spanning from Powell to Hyde Street. Performers are randomly assigned a rotation of 3-hour performance slots.

To be eligible for a permit, a performer must have “entertainer insurance,” which protects him/her from any public injury liability and insures equipment and instruments. This runs between $200-$300 per year.

Delegated wharf performance zones (via SFPort)

According to Darryl Johnson, who oversees the port permit system, 44 performers currently have either monthly or yearly permits and insurance coverage, though only 24 are active participants. This number peaks at around 36 active participants on any given day in summer, the busiest time of year on the wharf.

While the Fisherman’s Wharf Street Performers’ Program accrues roughly $20,000 in permit sales each year, it offers little in return for the performers who pay their dues and follow the rules. Dreyfuss claims that the system is routinely abused, with little official enforcement, rendering it ineffective.

The most prolific abusers of the permit system, according to Dreyfuss, are the “spray painters” who put on brief live art performances, then sell dozens of pre-made posters. Though these painters have port permits, Dreyfuss claims the sale of prepared art constitutes the majority of their sales and violates the terms of the program. “Teams of spray painters all selling the same Bob Marley, Scarface, SF Giants, Tinker-belle, Marilyn Monroe, and Hello Kitty posters — all mass produced and almost all trademark infringements,” he says.

Dreyfuss equates these “artists” to illegal vendors and says they rake in “2-3 million dollars or more a year in untaxed, unlicensed merchandise sales per year.” He fears that continued abuse of the permit system may ultimately lead to its demise (a similar permit system used in Venice Beach for years was recently shut down by a district judge). He explains his rationale, via email:

“Figuring very conservatively, each of the four currently permitted spray paint outlets take in at least $2000 on average. (There is a fifth spray painter in our program who works alone and refuses to be part of this corruption). In fact the average take per day is likely to be considerably higher on weekends and holidays. In any case, $2,000 X 4 storefronts = $8,000 X 300 days/year =$2,400,000 scammed through the Port Program alone.”

Omar and Diego, two spray paint artists situated at the corner of Mason and Jefferson, declined to comment on their earnings, though their ten-minute show drew a crowd that spilled well into the street and they auctioned off 12 pre-made paintings for $10 apiece in the aftermath. This cycle repeats 8-10 times on a busy day. Further down the wharf, a similar outfit produces similar results.

But how does this compare to other performers within the Fisherman’s Wharf permit system?

Emerson Ortis regularly plays keyboard and organ in spot 12, an abandoned parking lot on the isolated edge of Hyde and Jefferson. He’s been playing on the wharf for 30 years and says Hyde was once “bubbling with life,” but has since become more modernized and quiet. Ten years ago, he joined forces with Sahar Miller, a talented young Saxophonist, and on weekends, Emerson’s seven year old son joins the duo on drums. The group, GroWiser, is from Oakland, but commutes daily to perform along the wharf.

Emerson and the GroWiser Band (Zack Crockett)

On a typical day, Emerson says the band collectively makes $100-$150; of this, $35 covers the expenses of tolls, gas, food, and parking. On their best day ever — July 4, 2005 — they raked in $800, but those days are rare. Emerson claims that on weekdays, the best money is earned between 11 am and 3 pm when locals peruse the streets during lunchtime and tourists converge at the piers. “The power hours,” he calls them, with a hearty chuckle. Once a mechanic by trade, Emerson now makes this his full time job; his wife, a former street artist herself, is his booking agent, videographer, and biggest supporter.

The Oakland Breakerz, a troupe of eclectic break dancers, also makes a living along the wharf. The crew’s ringleaders, Nai Chao (Raw Sauce) and Thai Nguyen (Tye Breaker), explain that they “make San Francisco look good, pretty much.” After spreading out a piece of cardboard big enough to house one of the wharf’s sea lions, the group starts its 10-minute show, the first of 12 for the day.

“We make good money,” says Adam White, a crewmember who also operates a male enhancement website on the side. He and the other four members of the Oakland Breakerz have spent years developing relationships with local businesses and artists, and defending their turf. “Fights have gone down out here,” he adds, “a lot of memories, a lot of fights. Everyone knows us.” Despite occasionally attracting the attention of the SFPD, the Breakerz’ territorial gusto has crowned them the sole dance crew along the wharf.

When police don’t shut them down early for blocking sidewalk traffic, the Breakerz fare quite well. In the summertime, they “consistently pull in $100-$150 a day” per person — or $500-$750 collectively over the course of 5 or 6 hours. On bad days, they see $30-$50 a piece. At their best, they earn $370 per person. Last year, Raw Sauce bought a pre-owned 745 BMW with his dancing profits and claims his crewmembers also enjoy material success. “It’s inconsistent though,” says Tye Breaker. “The good days are real good, and the bad days aren’t even worth the gas to get here.”

In any case, they still don’t do as well as the spray artists, who the Breakerz claim can bring in “absurd money — $5,000 a day sometimes.”

Oakland Breakerz. Image via Myspace

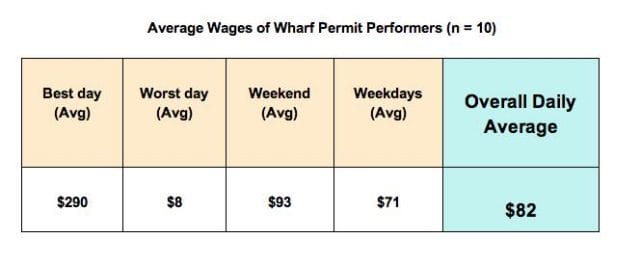

Overall, we interviewed 10 artists in the Fisherman’s Wharf permit program. Averages of daily earnings estimates are included below.

Fafa the Clown, who walks across broken glass with audience members on his back, does 4 to 5 ten-minute shows a day, and claims to draw in an average of $15 per hat (performance). He lives in a van with his circus acrobat girlfriend, and says the life of a vagabond entertainer is excruciatingly tough but worth the payoff, which comes in the form of freedom. He adds,

“It’s our constitutional right to perform. The port permit system is a monopoly — I’m not going to pay $500 for a right that’s free. I might get cited, but that’s part of life out here, whether you have a permit or not.”

Akron, a clown school graduate, chooses to make his living juggling bowling pins atop a 12-foot unicycle. Today, he has drawn a crowd of 50-60 people, above which he wavers precariously in the stiff Bay breeze. From Victoria, Canada, Akron invested a great amount of time and money to build up his act. He estimates that the clown school he attended in Paris set him back $5,000 for development courses and another $3,000-$5,000 for accommodations. His unicycle, custom built in Indiana by a man with 45 years of experience, set him back another $4,000.

Akron wobbles above the crowd (Zack Crockett)

He travels extensively around the country, and most of his earnings fund his itinerant lifestyle. He stays at hostels or couch-surfs with other performers to get by when he’s in expensive cities like San Francisco.

Musicians on Market Street

No permit system for street performers exists outside of the allocated wharf zone. While permit-less performers like Fafa and Akron can usually get by on the piers without being cited, musicians on and around Market Street aren’t so lucky. The crowded city center attracts musicians but is also rife with noise-sensitive business owners.

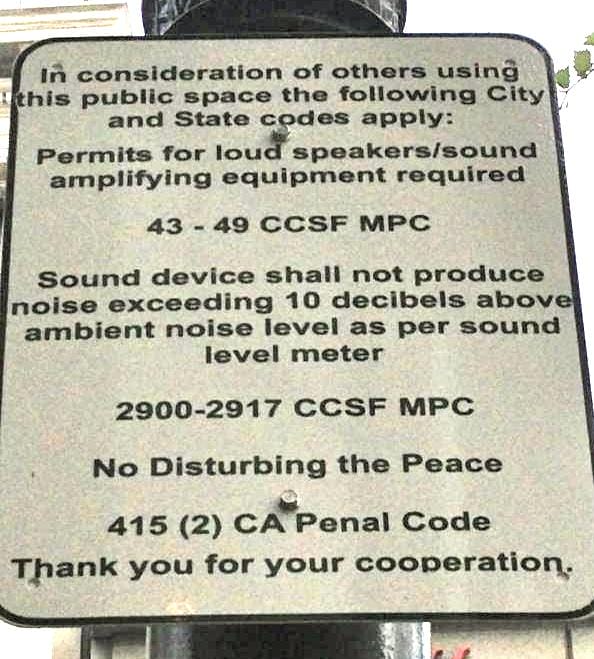

Musicians are often cited for not having these non-existent permits; we asked several city officials who oversee arts legislation to explain. Howard Lazar of the SF Arts Commission only reinforced that “performers are not included under the Street Artists Program.” Cammy Blackstone of the SF Entertainment Commission stated that any amplified acts require a loudspeaker permit. Outside of that, she says performers are “unable to protect themselves legally,” as there is no option for obtaining general, performance-related permits outside of the wharf.

The loudspeaker permit, offered through the Entertainment Council, runs $498 per year (2014), and is essentially the only legal option granted to musicians downtown (this is one of many benefits included in the $500 cost of the wharf permit system).But even if a performer manages to acquire a loudspeaker permit, he can be cited for noise violations when he exceeds the “local ambient noise level” (about 80-90 dB) by more than 10 decibels. He can also still be fined for blocking pedestrian traffic and for selling CD’s without a permit (which, of course, does not exist).

Permit sign in Union Square

Jordan B. Wilson, a “one man band extravaganza” who has been performing in front of the cable cars on Market Street for 5 years, is hesitant to go into his daily earnings, but adds that at his best, he was able to afford a studio apartment in the city with the tips made from his three-song circle shows. Recently, his spot was taken by a hot-dog vendor, who, unlike Jordan, had the ability to acquire a legal permit for that spot. Since being displaced, Jordan hasn’t fared as well and relies on friends for accommodation.

What’s worse is that Jordan, who makes every effort to play legally, has attempted to secure a loudspeaker permit without success. He has scheduled appointments and spoken with the Arts Commission, Entertainment Commission, and SFPD — all of whom have told him no such permit exists. He says they’ll go on about one day event permits, or the fact that bullhorns under 10 watts are legal, but ultimately tell him a general loudspeaker permit isn’t available. The Entertainment Commission’s website tells a different story.

“Almost daily,” the police shut Jordan down because of local business complaints from “the guys in the red hats.” These “red hats” represent the Union Square Business Improvement District (BID), an organization whose goal is to “enhance and promote the Union Square neighborhood for locals, visitors and tourists through beautification.” Businesses complain about street performers for a multitude of reasons, and when they do, they contact the BID, who in turn contact the SFPD.

An unnamed performer in the area accuses the BID of making concerted efforts to “gentrify Union Square,” and “wipe away” any scintilla of cultural energy that doesn’t mesh with posh retailers. Claude Imbualt, with the BID, counters that complaints are filed every day, and that the “nature, duration, and location of a performance” determines the citation. However, he also concedes, “Stores like Prada, a high-end retailer, expect a high-end ambiance. Someone banging on plastic bins outside takes away from that.”

The man Mr. Imbualt is referring to is most probably Larry Hunt, San Francisco’s own Bucketman. He taught himself drums at 3, and spent the time between helping out with his father’s shoe shine business listening to Buddy Guy records.

Larry Hunt, the “Bucketman” (Photo: Kevin Hazelton)

In his 22 years as a street performer, Larry has defined himself as a city fixture; you may recall seeing him featured in Will Smith’s “Pursuit of Happyness,” or a variety of other SF-based films and TV shows. With a smattering array of over 20 plastic bins, buckets, old pots and pans, he creates textural soundscapes and beats with objects most people merely store tennis balls in.

These days, Larry is getting a little harder to find. While tourists and romantics love him, local businesses complain constantly of his extended shows, and the BID and SFPD routinely shut him down before his act even starts. A 2008 online campaign fought to exonerate Larry from four $250 citations under the noise ordinance. Just a few weeks ago, he was slapped with a $460 fine for the same violation, and faces jail time if he fails to pay.

On a good day, Larry can earn $80 after nine hours of playing, which, in addition to his Social Security check, affords him an SRO room in the Tenderloin. He also teaches drum lessons for $6 an hour.

Despite legal threats, Larry still performs in his usual spot in front of the Old Navy on Market Street. “It’s all about rhythm,” he says. “If you’ve got rhythm, you can make anyone move.” Unfortunately for him, the SFPD can also make anyone move.

Furthermore, San Francisco’s Board of Supervisors is considering legislation that would allow the Department of Public Health to issue noise violations in addition to the resource-stretched SFPD. Supervisor Scott Weiner, who many musicians already regard as the antichrist of performance rights, says the proposal would empower the DPH “to cite violators, such as people playing drums in Union Square and in public spaces using amplified sound.”

Kevin Carroll, president of the San Francisco’s Hotel Council, has repeatedly doled out refunds to angry hotel customers who complained of excessive street noise, and is eager to eradicate performers from the area.

BART Performers

Source: Shawn Parker (Flickr)

There is one safe haven for downtown performers and it happens to be in the bowels of the city. BART, or Bay Area Rapid Transit, is San Francisco’s underground train system. With subway stations at at Union Square, Civic Center, and other downtown hotspots, BART attracts a variety of performers looking to entertain passing commuters. The transit organization gives out what is called a Permit to Engage in Expressive Activity, and it’s free. The BART police also maintain a lax policy regarding performers and volume levels.

Of course, with the freedom to perform comes a caveat: less money.

Kendra sings “spirit-themed” songs like “This Little Light of Mine” in the Powell Street station. Her voice is robust and echoes down the corridor, but she also uses a small karaoke amp to project — something she would need a loudspeaker permit for on the street. On a good day, she pulls in “close to minimum wage” — about $10.74 per hour. On a bad day, she walks out of the station with less than $15 for three hours of singing.

Another performer, keyboard player “Aja,” who plays in the Mission-24th Station, claims only “one out of a hundred people” give him spare change during rush hours. He averages about $9 an hour performing everything from Stevie Wonder’s greatest hits, to Lady GaGa. When we came back later in the day to check on his daily earnings, he had made about $50 in tips over the course of six hours.

Singer-songwriter John Vicino says he used to play for 8 hours in the Powell station and walk out with $20. After ascending onto Market Street, he made $50-75 in the same amount of time. So why doesn’t everyone play upstairs? Vicino explains,

“It’s weird, there’s like, a rule of the streets. There’s the whole, you got the people downstairs that worked their way up to the top, you know, and that’s the way it works. I started trying to play up top when I first started and they were like, ‘No, you gotta earn your rank, you gotta earn your stripes’ you know, that kind of thing.”

For Yeiner Perez, the man now infamous for performing naked acrobatic feats whilst sexually harassing commuters in the 16th Street BART station, this process was reversed. After gaining some popularity stilt-walking through the Mission, Yeiner began doing handstands and other stunts in the BART stations. He has said that a lack of appreciation and recognition for his performances drove him to madness.

In short, while BART stations offer free permits and a hospitable performance environment, they don’t seem like a great place to eek out a living in San Francisco.

Factors That Determine Success

Source: Victoria (Flickr)

The Sharp Brothers, an acrobatics and juggling street duo specializing in diabolo, cite three major factors that impact how much performers earn on the street.

1. Skill

Most street performers agree there is a correlation between what you put into your craft and what you get out of it. Generally, more skilled, rehearsed, cohesive acts pull in more money.

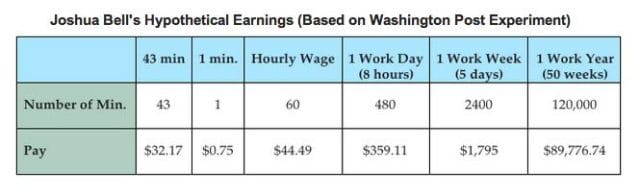

In 2007, The Washington Post was curious as to whether or not this was true and conducted an experiment: they stuck Joshua Bell, one of the world’s finest violinists, in the Washington Metro to see how he would fare. Armed with his $3.5 million Stradivarius, a disguised Bell played an incredibly demanding 43-minute set, earning $32.17. Out of the 1,097 people who passed by, only twenty-seven threw in money; a mere seven actually stopped to listen to the Grammy-winning virtuoso. Despite this, he fared better than most performers we interviewed.

Were Bell to hypothetically make this his full-time job, working 8-hour days, five days per week, his earnings could be expanded as follows:

To consistently maintain this level of performance for 8 hours, however, would be an inhuman feat. Most performers have fairly demanding routines and only perform 3-4 hours per day.

Still, at $44.49 an hour, Bell secured more than most street performers we interviewed in San Francisco. However, Nate Sharpe (of Sharpe Bros) explains that skill isn’t just mind-blowing talent; more important to monetization is one’s ability to “convince people en masse to stop, watch, and then pay you for the pleasure.” If Bell had made an effort to do this, he likely would’ve made much more, even if his playing weren’t as technically perfect.

Over three summers of performing, the Sharpe Brothers’ average revenue for a 45-minute show dramatically increased. They claim “the tricks stayed, by and large, exactly the same,” and that the major difference was that they “got better at talking to people, building a dedicated, engaged crowd, and delivering jokes in just the right way.” After honing these skills, the brothers were able to pull in well over $100 per 45-minute show; just three years ago, with an identical act but no crowd engagement, they earned as little as $10 an hour. Some level of PT Barnum salesmanship is just as important as performance ability.

2. Location

The first thing a performer looks for in a potential spot is foot traffic. However, a hoard of people doesn’t always equate to more money as the type of people in a given location is more important. For example, performers in leisure locations with high volumes of tourists (ie. Fisherman’s Wharf, Union Square) make drastically more on average than performers in high-volume commuter areas.

With 400,000 riders per day coming through SF-based stations, BART is a perfect example of how location is about more than just foot traffic. Performers in BART stations made, on average, 40% less per hour on a good day than those who performed along the wharf.

Weather, which can have a devastating impact on earnings, also impacts location selection. Emerson Ortis, a keyboard player along the pier, cites rain as his worst nemesis. “Performing outside is a poker game,” he says, “and rain is the worst hand you can get.” Even so, the weather in San Francisco is fairly mild, with only 70 rainy days per year on average. Most of the time, a little water doesn’t completely ruin a day for Emerson. “I’d say about 20-25 of those days, it’s bad enough to stop us.” For a performer along the wharf, this can equate to around $2,000 lost on spotty weather over the course of a year.

In New York, it’s a different story. Music Under New York (MUNY), not to be confused with San Fran’s MUNI, is a committee that governs some of the NY subway system’s most popular performance spots. During winter, hundreds of street artists, unable to brave the weather, flock to join MUNY and it becomes exponentially more competitive to secure one of the 70 available spots. Unless you’re the Naked Cowboy, performing in Times Square during a snowstorm probably isn’t ideal.

3. Number of Shows Per Day

The number of shows a performer can put on is completely contingent on his or her act. For instance, jugglers, clowns, and comedians prefer “circle shows,” in which there is an allotted routine (usually 10-15 minutes) that doesn’t begin until a crowd is secured (this is where skill comes into play). This type of show usually averages $15-$40 per hat, and most performers, depending on routine, will do 3-4 per day.

Other shows, like the Sharpe Brothers’ acrobatics and juggling routine, are so demanding and long (45 minutes) that they only perform once per day, usually for a large crowd at a much higher average hat. They write:

“Doing street shows is draining, both mentally and physically. Very few people can just pump out show after show…Your energy levels will drop, along with the revenue of the show. “

Musicians, robot men, and other static performers usually do a continuous 3-4 hour (or more) show, accruing small amounts of money over a longer time period. These types of performances are also generally less physically demanding and allow performers to continue if they are unsatisfied with what they’ve made.

Conclusion

In a city known for its entrepreneurial spirit, street performers are unheralded gurus. Each is his or her own CEO and must possess the drive, talent, charisma, and sense of humor necessary to thrive. They must craft marketable routines and convince complete strangers to give them money, all the while navigating through permits, city legislation, and competition. As FaFa the Clown tells us, “The best thing about street performing is the freedom, and the worst thing about street performing is the freedom.” Ultimately, a performer can’t be successful without self-motivation.

And even for the most self-motivated, long-term success can’t be achieved without consistency, which is a rare thing on the streets. A $200 day could just as easily be a $2 day, and no matter how impressive a routine is, chance and luck are always in play. While some full-time performers are able to earn a comfortable living, the inherent freedom of their career path rarely affords stability or security. Earnings are ultimately contingent on donations and good will.

So, the next time you see someone pouring out his soul on the street for chump change, keep this all in mind. If you’re still not convinced enough to throw in a buck, Nate Sharpe has something to tell you: “At the end of the day, you pay $5 for a burger, and most street performers are at least as entertaining as a burger.”

This post was written by Zachary Crockett. Follow him on Twitter here, or Google Plus here.