Photo by Essena O’Neill, Let’s Be Game Changers

Essena O’Neill decided to abandon her Instagram account—and her lucrative 580,000 followers—after she felt disgusted about accepting money from brands to pass off photo shoots as scenes from her life.

The 18-year-old Instagram celebrity had made thousands of dollars for each photo. But in October, O’Neill deleted most of her photos and edited the captions of the rest. “This has no purpose,” she wrote of a photo for a clothing company. “No purpose in a forced smile, tiny clothes and being paid to look pretty.”

The medium is new, but her complaints mirror the criticisms about gender stereotypes that have been levied against advertising, television, and other mass media for decades. She describes the incredible amount of makeup used to achieve a “natural” look, the focus on revealing clothing, and the careful staging of a photo that looks candid.

What is most remarkable, though, is how similarly O’Neill criticizes pictures she took herself. “NOT REAL LIFE,” she writes of a picture of her at the beach. “Took over 100 [pictures] in similar poses trying to make my stomach look good. Would have hardly eaten that day.” About a Facebook profile picture, she writes, “So here I was, at 15, forcing my little sister to take a picture of [me] in a revealing crop… with a massive push up bra.”

Many people critique how we curate and obsess over our social media presence rather than presenting our candid selves. Ms. O’Neill’s pictures show just how much we mimic Hollywood and advertising when we stage our lives online.

Few people spend as much time as O’Neill did on pictures for social media, but gender stereotypes are common throughout Instagram and Facebook. Even though we take our own photos, we shoot and share pictures as gendered as anything Don Draper would dream up.

We can say this with some certainty, because academic research has entered the age of the selfie.

The Quantified Selfie

When a group of German researchers, Nicola Döring, Anne Reif, and Sandra Poeschl, started downloading selfies from Instagram, they did so with a clear goal: to investigate whether the gender stereotypes that are common in mass media prevail on social media.

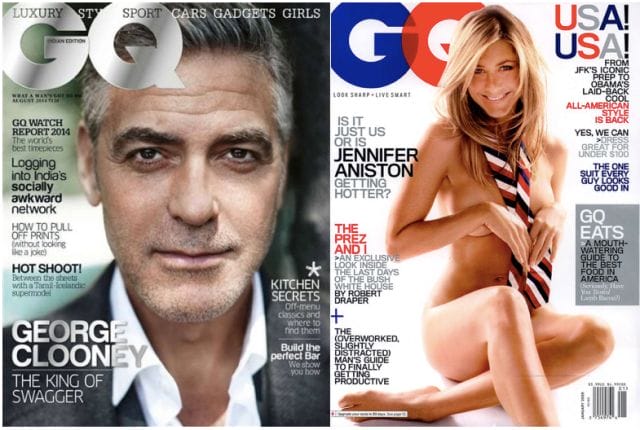

As they note in their paper, “How gender-stereotypical are selfies?”, criticizing stereotypical representations in the media has a long history. Academics have even formalized common ways in which women are depicted as weak and overly emotional. These range from the obvious—women wearing revealing clothing—to the subtle—women looking up at the camera while men look powerfully down, or women touching their hair or face.

To quantify the presence of gender stereotypes in Instagram photos, the researchers collected a random sample of 500 selfies, half of men and half of women, that were labelled with hashtags like #selfie. They then compared them to a sample of advertisements for mobile phones drawn from German magazines: three general readership magazines, 2 women’s magazines (like Cosmo), and two men’s magazines (like Men’s Health).

The research question was simple. Which images exhibited more gender stereotypes: the advertisements dreamed up by ad agencies or the selfies people took themselves?

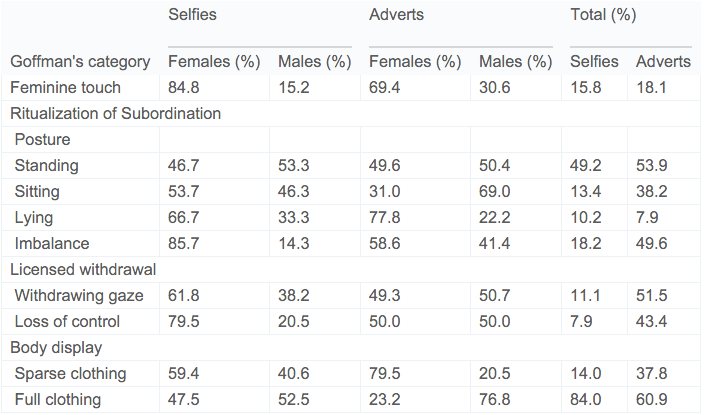

After counting up the presence of each gender trope in the images, the answer was clear: the selfies were very gendered, even more so than the advertisements.

Gender Stereotypes in Selfies vs Advertisements

Source: “How gender-stereotypical are selfies?” by Döring, Reif, and Poeschl

In 4 out of 6 categories, the selfies exhibited more gender-stereotypical behavior. This was especially true for the categories of imbalance, which refers to poses like the sorority squat or turning one’s head to the side, and loss of control, which indicates an exaggerated display of emotion like laughing uncontrollably or hugging a friend with a death grip. (You typically see men posing in a more controlled manner.)

The advertisements scored worse than the selfies only for the categories of sparse clothing and pictures taken of women lying down. It seems that many of our selfies would inspire critical articles from Jezebel and the New York Times if they appeared in ads or as magazine covers.

Thanks to Buzzfeed for convincing a sitting president to use a selfie stick

This study is not the last word on selfies and social media. People who take and tag selfies could be more inclined to copy mass media, along with its flaws, than the average Instagram user. The results could differ in other areas, and several hundred pictures is just a drop in the torrent of images produced by social and traditional media.

Yet other research supports the conclusion that we stereotype in our own social media pictures.

A study by Israeli academics of Facebook found that men’s profile photos “accentuated status (using objects or formal clothing) and risk taking (outdoor settings)” while women’s photos “accentuated familial relations (family photos) and emotional expression (eye contact, smile intensity).” Spanish researchers reached similar results while looking at photos uploaded by young people to the photo sharing and social networking site Fotolog.

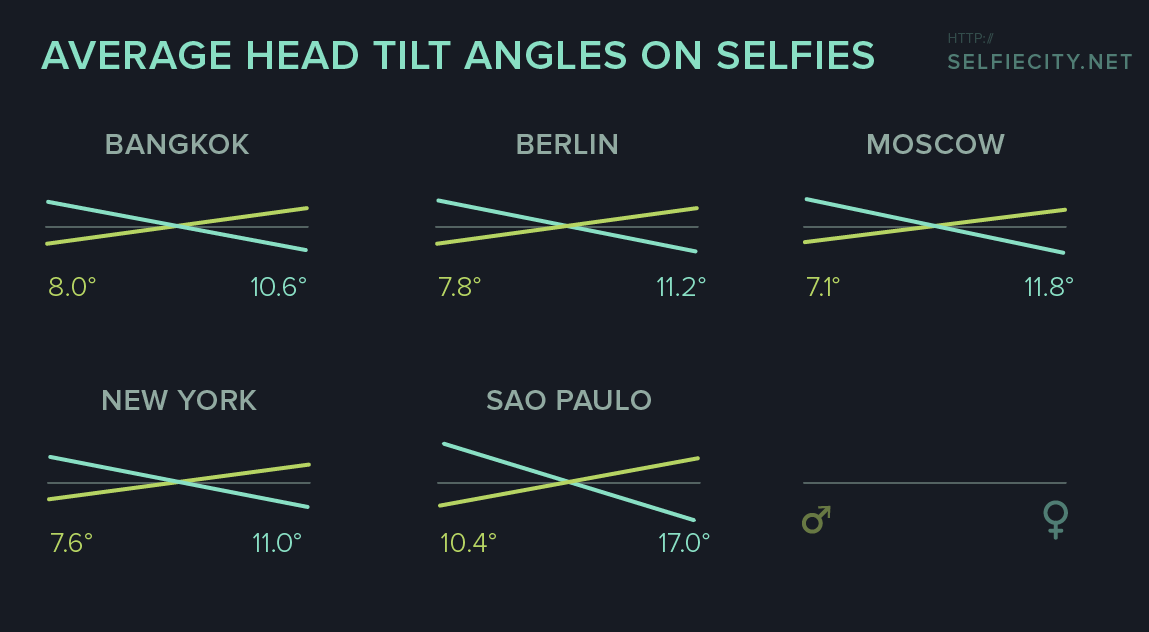

In Selfiecity, a project that used software to analyze 3,200 selfies from 5 cities, a team of data analysts discovered that women tend to look up at the camera (men look down) and have more exaggerated poses and expressions. Among teens and twentysomethings, the team confirmed, women do take the majority (65%) of selfies. But among older individuals, men take more selfies, which mirrors Hollywood’s obsession with young women and older men.

(The team also amusingly discovered that New Yorkers smile less than selfie-takers in Sao Paulo.)

We also suspect that most young people recognize these gender-stereotypical images from their own experience. When people talk about the poses that seemingly every girl strikes in pictures (the kissie face, the skinny arm, entwining a leg around a friend during a hug) or the pictures in every guy’s dating profile (the gym selfie, the picture with the bros looking cool), they are making the same observations—just without the critical interpretation.

Nothing to Lose but Our Selfies

Most academics describe their research as the early stages of documenting biases and stereotypes in social media—and validating it as worthy of study. They are only tepidly addressing the hard, chicken-and-egg question of whether social media users act out gender stereotypes as natural expressions of identity or to copy the images they see on television, magazine spreads, and billboards.

Photo credit: Selfiecity

It didn’t have to be this way. People criticize producers and advertisers for showing cliches rather than diversity. On social media, though, everyone has the ability to share images that express the full diversity of their lives. The ability to subvert cliches has also been democratized beyond Dove soap commercials.

To take a few examples, the hashtags #queerselfie and #feministselfie highlight images that defy norms and cliches. The “pretty girls making ugly faces” trend had fun demonstrating the same point made by Essena O’Neill: that beautiful pictures come from perspective as much as natural attributes. And social networks like Snapchat—with its disappearing images—have been described as an escape from the personal branding exercise that social media feels like to many.

But for now, the age of the selfie is an odd one. More and more of the media we see every day is produced by individuals expressing themselves. Yet it can feel as dishonest and shallow as the images produced by giant corporations. Because as we curate our social media presence, we, like advertisers and television producers, seem to turn to stereotypes and cliches, even though the target is ourselves.

![]()

Our next post is about how the KKK was a giant, racist pyramid scheme in the 1920s. To get notified when we post it → join our email list.

This post was written by Alex Mayyasi. You can follow him on Twitter at @amayyasi.