![]()

On an overcast Chicago afternoon in August 2013, hip hop artist Kendrick Lamar sauntered out onto Lollapalooza’s Bud Light stage. As thousands of twenty-somethings roared with approval, he grabbed a gold-plated mic and cut straight into the intro of “Backseat Freestyle:” Martin had a dream / Martin had a dream / Kendrick have a dream…

Just off to the side of the stage, on a raised platform, 36-year-old Amber Galloway Gallego thrust her hands in the air, and twisted her body to the rhythm. Clad in a purple shirt, and sporting a pink-tinted pixie haircut, she was also in the midst of a dream: to make music — particularly rap — accessible to deaf people.

As an American Sign Language interpreter who specializes in music performance, Gallego has interpreted over 300 rap, R&B, and rock concerts, and has worked with everyone from Aerosmith to Destiny’s Child. After a deaf friend told her that “music wasn’t for deaf people,” she embarked on a quest to prove otherwise; today, she’s hired by major music festivals all over the United States to make auditory performances more relatable for the deaf.

To do so, she employs a tireless mixture of hand signs, facial expressions, body movement, and sensibility.

Following Signs

Gallego (far right), with high school friends

Growing up in a “rough and tumble” San Antonio, Texas neighborhood in the 1980s, Gallego vied to be America’s first widely-recognized white, female rapper. With her middle school posse in tow, she spent her hour-long lunch period spitting verses under rusty swing sets, and “trying to be all that.”

Beyond her tough front, Gallego had a series of serendipitous experiences with deaf people that would shape her future.

“When I was 5, my dad started seeing a woman who had a deaf son,” she says. “He was a boy scout, and he taught me my first sign ever — ‘camp.’” A few years later, her babysitter gave birth to two children, both of whom were deaf; Gallego watched them grow, learning signs as they developed. In high school, a deaf athlete on the football team tore a ligament, and Gallego, who by then knew “just barely enough signs to communicate,” helped him through the recovery process by signing him certain exercises.

As a high school junior, Gallego was involved in a horrible car accident and ended up bedridden in the hospital for months. Her roommate, who was coincidentally deaf, became her close friend. “She was a 24 year-old who’d been hit by a car she didn’t hear coming, and had been been crippled for life,” says Gallego. “Nobody would talk to her, so I started signing with her. We became good friends.”

In the aftermath of her accident, Gallego dropped out of high school prematurely, spent a year learning to walk again, and endured hundreds of hours of painful physical therapy. As soon as she recovered, at 17, she got pregnant and gave birth to a set of twins. But her setbacks and new responsibilities did little to quell her ambition: she completed her GED, and continued onto community college, where she was eventually was encouraged to join an interpreter training program and study American Sign Language (ASL).

![]()

Shortly into her curriculum, Gallego was invited to a performance put on by the San Antonio Deaf Dance Company, a leadership program taught by dance troupe, The Wild Zappers, that inspires deaf high schoolers to learn dance routines. The event proved cathartic for her:

“They had these choreographed hip hop dances, with sign language incorporated. And they were right on beat, fully immersed in the song, feeling the instrumentation. For the first time, I realized that deaf people could enjoy music with the right nurturement. The hair on the back of my neck stood up, and I realized there was something to this.”

Gallego began organizing parties every Friday night at her home, where her deaf and non-deaf friends could mingle, learn from each other, and collectively enjoy music.

One Friday night, Sir Mix A Lot’s “Baby Got Back” came on, and Gallego decided, on a whim, to get up and start signing the lyrics. “My deaf friend said, ‘Wow, they play stuff that dirty on the radio?’ She couldn’t believe it,” says Gallego. “But then she laughed and said, ‘You’re really good at this — we’ve never seen an interpreter do anything like it.’”

Backed by words of encouragement, Gallego went out looking for an opportunity to make music accessible for deaf people.

Welcome to the Rodeo

At the time, the largest venue in town was the rodeo. The huge arena, which drew big name acts, included a sign language interpreter in the corner for every show, but they weren’t expressive, and often did little to translate the subtleties of music for deaf attendees. “They would just sign the literal words, and would hardly move,” she says. “It wasn’t a representation of the music at all, and it certainly didn’t inspire the deaf people to care for the music.”

As a result, the 25 to 50 deaf attendees typically at the rodeo’s shows would be completely disengaged.

“They’d tell me, ‘Amber, music is a hearing thing. It’s not for deaf people,’” recalls Gallego. “Music meant so much to me, and all I could think was, ‘How can I translate this for them?’ “And then I remembered how much they enjoyed the San Antonio Deaf Dance Company performances, and realized it was all about movement.”

On a Spring day in the late 90s, Gallego approached one of the rodeo’s directors, gave her a performance to demonstrate her abilities, and convinced her to let her take the stage.

For Gallego’s first professionally interpreted rodeo show, she was stationed to sign for R&B group Destiny’s Child. “I just got up there and did my thing,” she says, “and people were like, ‘Wow, we’ve never had a connection to the music before, but now we do.’”

The gig went so well that Gallego ended up taking over the rodeo’s interpretation duties for the next four years.

Gallego signing for Snoop Dogg

Over that time span, she interpreted 22 shows, hired a team of four ASL performers — two for the actual rodeo, and two for the music events — and redefined the way that deaf attendees interacted with the shows.

Whereas previous interpreters had been flat and dull, Gallego performed with unbridled passion: her hands cut the air with rapid, precise signs, her mouth and tongue moved as if possessed, and her whole body jolted rhythmically with the beat and music.

“I signed for everyone from Aerosmith, to Lynyrd Skynyrd, to Snoop Dogg,” she says. “Country, R&B, grunge, rap: you name it, I did it.”

In 2014, after spending a few years working for other music interpreting companies, Gallego founded her own business, Amber G Productions.

The Harrowing Process of ASL Translation

Gallego (pink hair) with her team of interpreters

Today, Gallego and her team of music interpreters are mostly hired to work big festivals like Austin City Limits, as well as local venues in her home state of Texas.

Her job relies on a relatively recent law enacted by Congress. Under 1990’s Americans With Disabilities Act, concert venues are required to provide interpreters for deaf attendees — but only if they are requested. Though this law seeks to treat deaf people equally, the request process is incredibly arduous and, more often than not, dissuades the deaf and hard of hearing from attending. Gallego explains:

“If I want to go to a concert tomorrow, I just buy a ticket and go. A deaf person has to email the venue, find the right person (they’re not easy to find), request services, then request specific interpreters. Most of the time, even after going through this whole process, which takes weeks, the deaf person doesn’t end up with the right connection to the artist.”

Often, the interpreters provided by the venue are subpar, and not specifically trained to sign music. Gallego is part of a very small community of interpreters that have specialized in the technique, and it is an incredibly harrowing process.

Typically, she’ll be hired to interpret for every artist requested at a given festival. She is rarely ever given a set list in advance, and must memorize every song by those artists — sometimes up to 150 — to ensure she’ll be prepared to sign anything.

The process starts two months before the show. First, she’ll research the artist and hunt down every set list he played over the past five years. She then scans Spotify and iTunes for his most downloaded songs (this gives her a rough idea of the tracks that will, with certainty, be on the playlist). Once she’s done this, she turns to YouTube to watch videos of the performer in action.

“I’m looking for his body movements, and the way he presents himself on stage,” she says, “because as an interpreter, I need to channel that through me.”

Then, the real work begins: she listens to each song, memorizes the lyrics, and makes a “storyboard,” in which she breaks the track down into themes, each with a specific message to convey.

“The hardest person I’ve ever interpreted for is Jack White,” says Gallego. “He has no set list: even his own bands have no idea what they’re performing when they take the stage. And his lyrics are very symbolically dense.”

How Music Sign Language Works

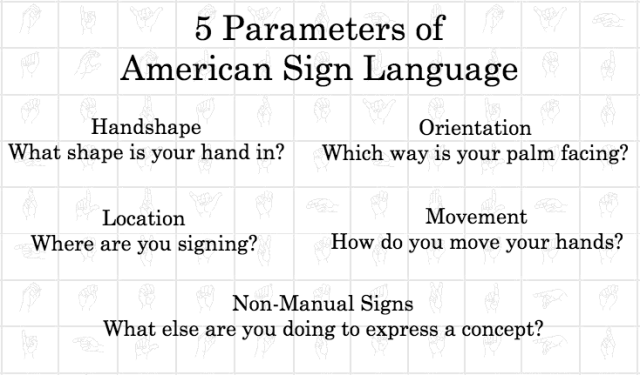

The problem with many music sign language performances, argues Gallego, is that most music interpreters lack a “dynamic equivalent.” ASL, like spoken language, has grammatical and syntactical rules to follow, and flashing the correct hand signs is only one of five parameters used to speak or translate:

Priceonomics

One of the most important, and oft-overlooked of these, is “non-manual signs,” which includes using things like facial expressions, head tilting, shoulder raising, and mouthing to create meaning, connote a certain tone, and match the intonation of the speaker. “If I didn’t express these things,” says Gallego, “it would be comparable to a world without inflection:”

“When you’re at a council meeting, the interpreter looks bored and serious to match the dynamic equivalence of the setting. The unfortunate thing is a lot of music translators look like council interpreters on stage: they don’t express the intricate, layered emotions of music.”

One challenge Gallego faces is translating metaphorical concepts from songs without compromising the whimsical nature of the lyrics. To navigate these intricacies, Gallego will often employ what she calls “indicating verbs:” she’ll mix two signs concurrently — one with her hands, and the other through her movement — to get an idea across.

For instance, in “Baby Got Back,” Sir Mix A Lot pontificates, “My anaconda don’t want none unless you got some buns.” When signing “anaconda,” Gallego combines the hand sign for “snake” with a sweeping motion that connotes she is referring to a penis. “I’m signing the snake, but visually, it looks like a big schlong,” she says, “and the audience gets it.”

Signs from Sir Mix A Lot’s “Baby Got Back”

Similarly, Gallego can’t just flash the sign for “butt” (literally, a simple finger point to the exterior); she has to symbolize that Sir Mix A Lot is referring to particularly voluptuous posteriors. Instead, she draws the shape — a gigantic, large-bootied silhouette — with her hands in the air. “You have to add action and movement to express his true lyric,” she says.

Gallego rarely signs the exact words a performer is saying. Instead, she’ll relate the concepts behind the lyrics. This is because literal interpretations more often than not confuse people (ie. for the phrase, “bear with me,” some interpreters flash the sign for the animal).

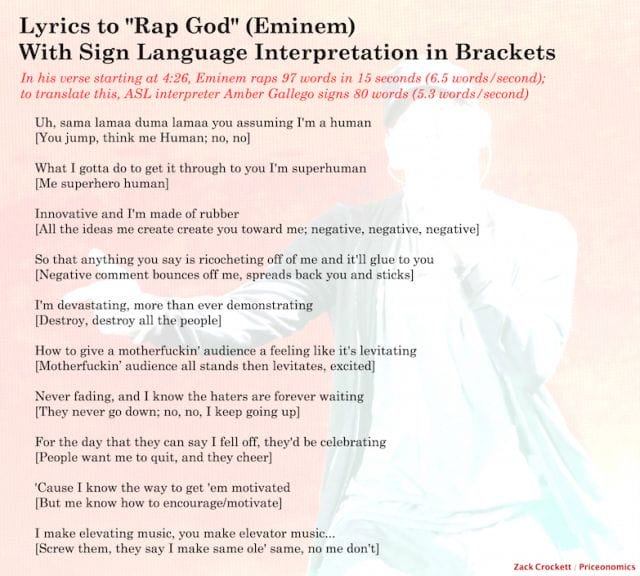

In “Rap God,” there is a 15-second section where Eminem raps 97 words (a “supersonic” rate of 6.5 words per second). It would be impossible for Gallego to sign every one of these words; instead, she expresses Eminem’s concepts with a certain shorthand:

Priceonomics

When a rapper says, “I don’t give a fuck,” Gallego will instead sign the equivalent of “I don’t care,” then add the movement for “fuck,” to connote the intensity of the statement. Her policy on including dirty language is non-wavering: “You have to include it, it’s a form of empowerment,” she says. “To not include it is audism — it’s a form of oppression for deaf people, where you can hear a word, and they’re not privy to it.”

Just as with spoken American language, sign language also has regional variations. With each of her performances, Gallego makes sure to learn the slang of whatever state the concert is in. While preparing for Kendrick Lamar in 2013, she asked a group of deaf kids what the sign for “blunt” was, just to ensure her audience would be well-informed.

The Pay Off

For all of her tireless work, Gallego is paid a comparatively small sum, usually, $500 or less for a whole concert. But as an interpreter, she says, “the payoff is emotional, not financial.”

“Sometimes, when I look out and see deaf people moving, and signing, and jamming out in the audience, I can’t hold back the tears.” she says. “There’s a raw understanding of language and music that’s happening.”

For Gallego, signing is a labor of love. In her spare time, she runs a YouTube channel, where she’s posted 62 videos of ASL interpretations of famous songs — everything from “Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer” to Sam Smith’s “Stay With Me” — just to provide a much-needed resource for deaf music aficionados. She receives over 150 requests every week.

And though her work has partnered her with some of the music industry’s biggest names, there are still a few things Gallego would like to check off her bucket list.

“I’d love to sign with Jay-Z,” she says. “That would be a dream.”

![]()

This post was written by Zachary Crockett. You can follow him on Twitter here.

To get occasional notifications when we write blog posts, please sign up for our email list.