“There are but few men who are sufficiently attentive to their own thoughts, and able to analyze every motive or action. Among these, Timothy Dexter was not one.”

~ Samuel L. Knapp (1848)

![]()

Lord Timothy Dexter was many things.

He was a famed 18th century entrepreneur — one who made a series of apparently harebrained transactions, and somehow emerged handsomely rewarded each time. He was a poor, uneducated leather craftsman who, by fortuitously (and stupidly) speculating on the Continental dollar, became one of the richest men in Boston, and who then unsuccessfully lobbied for entry into elite social circles for decades. He was, in his own words, a “Classic Progressive ‘Libperel’” — and despite his atrocious spelling, he was also a published author and self-proclaimed philosopher.

Lord Timothy Dexter was many things, but he was not a Lord: this was a title he bestowed upon himself, with great personal satisfaction.

Most importantly, Lord Dexter was one of America’s first famed eccentrics — yet, in the annals of history, he has been largely forgotten. This is a tragedy. Though he constantly yearned to be accepted, Lord Dexter refused to compromise his strange ways; in doing so, he paved the way for all aspiring American weirdos.

Birth of a Legend

In the late winter months of 1748, several miles outside of Boston, Timothy Dexter was born. From his birth, he fancied himself a legend — “I was to be one grat [sic] man,” he later wrote — though initially, destiny was not on his side.

He came from a family of farm laborers who, in the times of British colonialism, saw little financial stability. Nonetheless, by the age of 16, Dexter secured himself an apprenticeship with a Boston leather dresser and began working toward a career as a craftsman. Though the profession was generally considered “lower class,” the money was good: by the 1760s, Dexter’s Boston teachers had monopolized the art of crafting “Moroccan leather,” a material that was in high demand by colonial fashionistas.

At the age of 21, Dexter completed his apprenticeship, and decided to go into business for himself, producing leather gloves and moosehide breeches. Though the situation in Boston quickly deteriorated– in rapid succession, the British imposed “taxation without representation,” residents revolted with the Boston Tea Party, and the government closed the city’s ports — Dexter decided to stay local. Armed with nothing more than a “bindle” (hobo-stick) pitched over his shoulder, Dexter migrated to Charlestown, Boston’s leather epicenter.

It was here, through his first twist of fortune, that Dexter met (and charmed) Elizabeth Frothingham, the wealthy, newly-minted widow of one of his former leather associates. She was an industrious, frugal woman who’d made “no inconsiderable profit” as a huckster, selling door-to-door goods. Enamored less by her nature than her worth in hard cash, Dexter took her hand in marriage.

Rise to Wealth

In Boston’s well-to-do Charlestown neighborhood, Dexter was an instant misfit. His new neighbors — the likes of whom included John Hancock (then-Governor of the Commonwealth) and Thomas Russel (then one of the richest men in the country) — were America’s nobility, well practiced in etiquette and business affairs. As an uneducated, “lowly” man who’d married into money, Dexter was not seen as an equal. This, of course, infuriated him, and he set out to prove his decency.

After observing his gentleman peers, Dexter decided he’d first go about this by securing a seat in public office. As best as a man who’d dropped out of schooling at the age of 8 could do, Dexter submitted dozens of petitions to the the neighboring Malden, MA governing body until (most likely out of utter exhaustion) they created a post for him: “Informer of Deer.” Under the title, Dexter was required to keep track of the town’s fawn populations — though, as the annals of Malden’s government records note, “the last deer had disappeared from the Malden woods nineteen years before.”

Satisfied with his new duty, Dexter set out to multiply his wealth — and in true Dexterian form, he found an odd way to do so.

At the onset of the Revolutionary War in 1775, the Continental Congress (created by the 13 colonies to counter British rule), issued America’s first form of paper currency, the Continental dollar, which ranged in value from ⅙ of a dollar to $80. During the revolution, the currency was severely undermined: though Congress issued some $250 million worth of the bills, vendors, not trusting the currency’s value, refused to accept it — despite numerous efforts by Congress to punish non-participating shop owners. Eventually, Congress was forced to print more; soon, the bills flooded the market and rapidly depreciated in value:

“In November of 1776, $19 million in Continental currency had been issued and one could still buy $1.00 worth of goods for $1.00 in paper. By November of 1778, $31 million had been issued, and it took $6.00 in paper to buy the same amount. By November 1779, $226 million was in circulation and it took $40.00 in paper to buy $1.00 in goods.”

“Not worth a Continental” became a common phrase used to denote the utter lack of a good’s value. Following the war, soldiers, who’d been paid in Continentals were destitute and Dexter’s rich neighbors, Hancock and Russel, took it upon themselves to buy back some of these bills “to boost public confidence and do a good deed.”

A $55 dollar Continental dollar, issued in 1779

Dexter, ever-observing and yearning for respect, emulated these men to an extreme. Realizing that Americans were willing to part with the now-discontinued Continentals for anything they could get, Dexter gathered up all his savings (and those of his wife) and purchased boatloads of the bills for fractions of pennies on the dollar. It was a bold and idiotic move — he was essentially bargaining his entire livelihood on the chance that this currency would be reinstated — with little chance for pay-off.

By some miraculous stroke of luck, his gamble proved to be fruitful. When the United States Constitution was ratified in the 1790s, it was stipulated that Continentals could be traded in for treasury bonds at 1% of face value, largely at the behest of Alexander Hamilton. Since he had purchased massive amounts of this currency at a fraction of this cost, Dexter became instantly and astronomically wealthy.

What’s more, at the questionable advice of a neighbor who’d taken a disliking to him, Dexter had also purchased large quantities of European currencies (British pounds, French francs), which he was now able to flip for a handsome profit.

Surely, thought Dexter, this new wealth would gain him credibility with his peers. This was not the case. Dexter’s repeated efforts to break into the elite circles of the upper crust were, each time, deterred by his “crude” rhetoric, distasteful nature, and inability to keep his mouth shut at inopportune moments.

Ultimately, Dexter concluded that his rejection was a result of the Bostonians’ stodgy nature, and not of his own eccentricity. With a flippant farewell, he gathered his wife and children, and moved north to the coastal, mercantile town of Newburyport, Massachusetts.

Here, he flourished.

A Princely Estate

Newburyport, in the late 1700s, was a supposedly idyllic town — a place where “rich and poor mingled,” and where the “population was not so large as to hide any individual, however odd or humble.” Though possessing only one of these traits, Timothy Dexter wasted no time in taking advantage of his arrival.

With his new fortune, Dexter purchased a healthy fleet of shipping vessels, a stable of brilliant cream colored horses, and a lavish coach adorned with his initials. Then, in grand fashion, he erected a “princely chateau” overlooking the sea — a chateau, it should be noted, that included the most lavish furnishings on the market, right down to its “tasteful and commodious outhouses.”

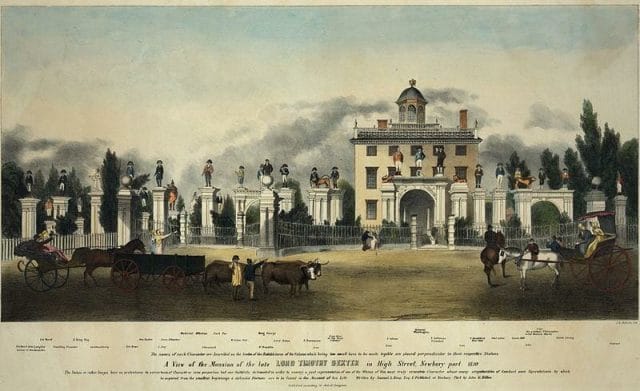

As recounted by a 19th century historian, Dexter then hired the “most intelligent and tasteful” artists of European architecture to carve and mount a series of more than 40 giant, wooden statues on his property, each depicting a great character in American lore:

“…The tasteless owner, in his rage for notoriety, created rows of columns, fifteen high feet at least, on which to place colossal [statues] carved in wood. Directly in front of the door of the house, on a Roman arch of great beauty and taste, stood general Washington in his military garb. On his left was Jefferson; on his right, Adams. On the columns in the garden there were figures of indian chiefs, military generals, philosophers politicians, statesmen…and the goddesses of Fame and Liberty.”

Not to be outshined, Dexter then erected a final statue — one of himself. Beneath it, he boastfully painted an inscription: “I am the first in the East, the first in the West, and the greatest philosopher in the Western world” — this, coming from a man who’d neither contributed anything to the field of Philosophy nor ever read a single book on the subject.

A rendering of Dexter’s estate, complete with statues

At $2,000 a piece, the 40 statues cost Dexter twice as much as he’d paid for his entire estate — but with them, the outcast achieved his ultimate aim: to garner the public’s attention. “It made the bumpkins stare,” writes Samuel L. Knapp, “and gave the owner the greatest pleasure.”

In time, Dexter began to garner the wrong kind of attention. His estate became so much of an aesthetic embarrassment that his wife soon abandoned ship to live elsewhere in the neighborhood; in her absence, Dexter’s son — a morose lad who, like his father, took no joy in learning — moved in. In short order, the home was turned into a “bagnio” (brothel) of sorts: long nights of drunken buffoonery ensued, in which women came and went, and the fine interiors (including curtains once owned by the Queen of France) were soon covered in “unseemly stains, offensive to sight and smell.”

The Enterprising Eccentric

When Dexter purchased several large ships and announced his intentions to launch a business in international trade, his fed-up neighbors reportedly seized the opportunity to provide him with horrible investment ventures, in the hopes that he’d bankrupt himself and be forced to move.

One of these neighbors recommended that Dexter sell warming pans (wide, flat brass pans with long handles used for warming beds in the 18th century) in the West Indies (a European colonial territory known for its year-round hot weather). The trusting Dexter purchased no less than 42,000 of the pans, dispersed them in nine shipping vessels, and set off to sell them — his actions, all the while, eliciting thunderous laughter from experienced traders. But it was Dexter who got the last chuckle: when he arrived and found no need for warming devices, he rebranded them as ladles and sold them to sugar and molasses plantation owners. The demand was so great that each owner clamored to buy at least three or four; Dexter marked up the pans by 79%, and returned with an even greater fortune.

In another instance, a trader maliciously convinced Dexter that there was a great demand for anthracite coal in Newcastle. Unbeknownst to Dexter, a large coal mine already existed there, rendering any foreign shipment useless. When Dexter arrived, the mine was, miraculously, on strike, and the coal was purchased at a considerable mark-up. Once again, Dexter returned victorious, with “one [barrel] and a half of silver” (because what sort of distinguished gentleman didn’t keep his silver in barrels?).

By this time, through his exploits, Dexter actually began to acquire a considerable knowledge of trading techniques. At least one 19th century biographer argues that, from this point forward, his actions weren’t acts of stupidity or ignorance, but rather “quite sane” sales ploys by Dexter to dupe his doubters. As his fortune bloated, he began to realize that he could simply inquire which good was scarce in the market, purchase as much as he possibly could of it, then double its price and sell it.

With precision, he enlisted this strategy — though his goods of choice were often incredibly odd.

Once, Dexter traveled to Boston and purchased an astronomical quantity of whale bones — such a large amount that he managed to completely monopolize the article’s market, and was able to charge his own price. In total, he amassed some 340 tons of whale bones, which he then off-loaded at a 75% mark-up for use in goods like ladies’ corsets, collar stays, buggy whips, toys, and even typewriters. Whale bone and baleen was so prominently in demand, that today we remember the material as the “plastic of the 1800s.”

Whalebone corsets: all the rage in 18th century womens’ fashion

“I found I was very lucky in spekkelation,” the nearly illiterate Dexter later wrote (indubitably, he meant “speculation”). “Spekkelators swarmed me like hell houns.”

But Dexter also wasn’t above using dirty tricks to sell his wares. He once bragged about purchasing wholesale bibles at “12% under half price” or 41 cents each, then selling 21,000 units in the West Indes through manipulation. “I sent a text that all of them must have one bibel in every familey or if not thay would goue to hell,” he wrote, with little regard for spelling. He then told his prospective buyers that if they wished to repent to go to heaven, his captains were ready and waiting with a full supply.

In a matter of weeks, Dexter had cleared $47,000 worth of holy books.

Call Me ‘Lord’

By the end of the 18th century, Dexter had established himself as the defining eccentric of not only Newburyport, Massachusetts, but all of the Eastern states. Tales of the man’s wealth and antics circulated far beyond his coastal town; though Dexter believed in no such thing as “bad” attention, he garnered it in droves.

He yearned, more than ever, to be accepted as a noble, wealthy gentleman, but his actions built a stone wall between him and those he emulated. To gentrymen, Dexter reeked of poor taste and lack of education — and their suspicions were affirmed though the man’s antics.

Dexter would often repaint his statues’ inscriptions (time to time, he’d take great joy in rewriting history). Once, an unfortunate painter wrote “Declaration of Independence” under the Thomas Jefferson statue; Dexter demanded he correct it to “Constitution” (an incorrect attribution). When the painter insisted that his own inscription was the correct one, Dexter removed his Longrifle and fired a shot at him, narrowly missing. “Constitution,” he repeated again, with a solemn tone. This time, his painter obliged.

Emulating his wealthy neighbors, he purchased a lavish library of books, but never indulged in reading for more than ten minutes at a time; after learning of English nobility’s passion for paintings, he ordered a servant to amass a brilliant collection, and “gave himself no rest until he had commenced a gallery.”

While in pursuit of respect from the upper class, Dexter conversely surrounded himself with the most eccentric, off-beat characters he could find, likely the only people willing to befriend him.

These folks included one John P. — a man from a respectable family who, after being rejected as a schoolmaster, became an outcast and opened his own school. He was a man of “perpetual contradictions,” who stoically imparted “scientific” wisdom on his pupils with no knowledge or training on the subject. He quickly became Dexter’s best friend and motivator.

He struck a similar friendship with Madam Hooper, a rich, local widow-turned-fortune-teller who, among other things, gave Dexter astrology advice in exchange for tea.

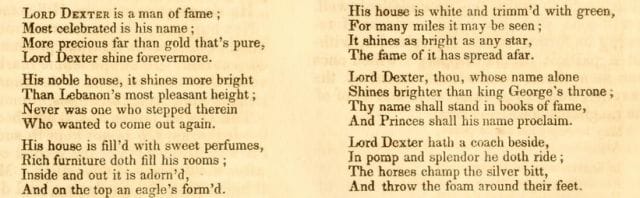

Most famously, in imitation of the King of England, Dexter hired his own poet laureate — a hapless 20 year-old who he’d found in the market, selling halibut from a wheelbarrow. After learning that the great Italian poets were crowned with mistletoe, Dexter concocted his new lyricist a coronet of parsley (the only thing he had in his garden at the moment), and forced him to write and recite fawning poems that boosted his own self esteem:

Still, the poems did not fulfil Dexter’s need for adulation. Often, he’d take to the streets of neighboring towns, stopping strangers to ask them if they knew of “the greatest man in the East.” Regardless of his victim’s response, Dexter would dramatically relate his own fanciful, self-gratifying tale.

Soon, he declared himself ‘Lord’ and insisted that his guardsmen, servants, and crew members refer to him as such. By this point used to his antics, they asked no questions: he became Lord Timothy Dexter.

But Dexter was no fool: despite all of the forced adulation, he could still sense that his peers did not respect him, and this greatly bothered him. So, in a moment of “God complex,” Dexter decided to fake his own death. In doing so, he hoped to see how the public really felt about him.

His preparations began with a tomb — a grandiose, well-ventilated room that occupied the entire basement of a fine summer home. Then, the prankster hired the best cabinet-maker in Massachusetts to craft a coffin from the finest mahogany wood available — so fine, that upon its completion, Dexter took to sleeping in it for several weeks with great comfort and satisfaction.

With the logistics of his test in place, Dexter enlisted a few of his trustworthy men to organize a mock funeral, and disseminate small cards with the news of his death to the community. His wife and two children were let in on the hoax, and he demanded that they “act the part” — that is, that they cry and appear utterly distraught over his parting.

On the day of the ceremony, some 3,000 people showed up. It was a grand affair, where only the fanciest wines and most exotic liquors were poured; from below a board of wooden planks, Dexter observed the scene with glee. Everything seemed to be going smoothly: his son was “sufficiently drunk to weep without much effort”, and his daughter’s head was buried in her hands. Then, in a moment of panic, Dexter he saw his tear-less, smiling wife.

He approached her secretly in the kitchen, then callously “caned” her for her lack of effort, causing a great commotion. As the other guests entered the room, they were greeted by the supposedly-dead Dexter, who now housed an ear-to-ear grin. The red-handed idiot then proceeded to go about carousing with his mourners, as if the whole stunt had never happened.

“A Pickle for the Knowing Ones”

Lord Timothy Dexter knew that to achieve his ultimate goal — immortality — he’d have to follow in the footsteps of every great man before him and publish a memoir.

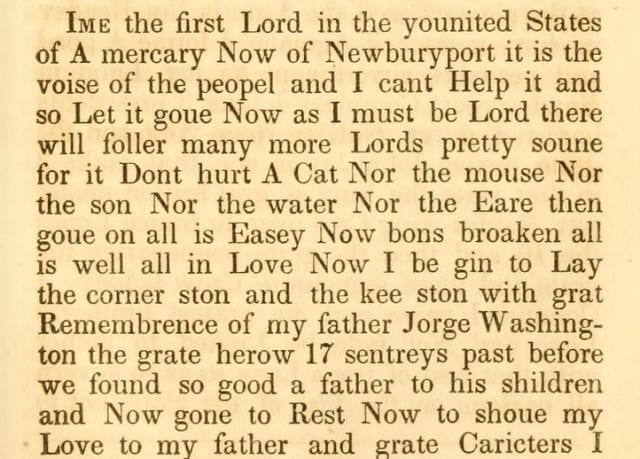

Despite his complete lack of knowledge (or care) for writing and penmanship, he set out to compose a work that would out-wit Shakespeare, and rival the learnedness of Milton. His working title (which, of course, made absolutely no sense): “A Pickle for the Knowing Ones, or Plain Truths in a Homespun Dress.” The book was atrociously misspelled, and entirely devoid of punctuation — there were no periods, no commas, no dashes or semicolons — it was merely a jumbled mess of nearly incomprehensible writing.

Though it is likely that his grammar errors were a result of Dexter’s lack of education, he likely exaggerated his mistakes to mock those who excluded him. “He had a distrust of anyone with a college education, and he liked to rub their nose in it,” claims literary historian Paul Collins. “He’d say, ‘I have the money to publish books too, and I can do whatever I want.’”

Here is, for example, the first page of “A Pickle…”, in which Dexter proclaims himself “the first Lord in the younited States of A mercary” (note the misspelling of “George Washington” despite his idolatry of the man):

Dexter realized that most noblemen in England didn’t sell their books, but rather gave them out as gifts to increase readership; he followed suit, standing by the roadside, handing copies to passersby. In time, his masterwork was appreciated — if not by merit, by its nature as a complete oddity.

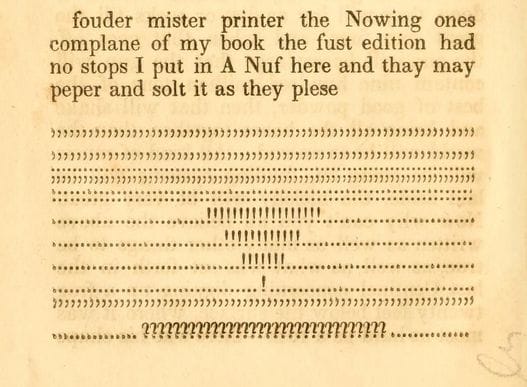

Demand was so high that a second edition was printed. This time, at the behest of his editor, Dexter included a full page of punctuation marks at the end, with a simple instruction for the reader: “pepper and salt them as you please.”

Nearly a century later, Dexter continued to receive glowing, if not quasi-satirical, praise for his effort. In an 1890 copy of The Atlantic Monthly, author Oliver Wendell Holmes related his thoughts on Dexter’s literary ability:

“I’m afraid that Mr. Whitman and Mr. Emerson must yield the claim of declaring American literary independence to Lord Timothy Dexter, who not only taught his countrymen that they do not need to go to the Herald’s College for their titles of nobility, but also that they were at perfect liberty to dispel just as they liked, and to write without troubling themselves about punctuation of any kind.”

Dexter had set out to “exhibit to mankind an example of universal genius not to be easily paralleled in the history of human intellect” — and in one way or another, he’d achieved just that.

All Great Men Die

On October 26, 1806, just a few years after publishing his book, Lord Timothy Dexter quietly passed away — this time, for real.

“It is hard work to be a Lord,” he once wrote, and his life was no exception: he’d imbibed copious amounts of wine and liquor, had procured various illnesses from his extensive travels, and had, on more than one occasion, gambled his life in foolhardy adventures.

In the last days of his life, Dexter sought to atone for his errors, and attempted to undo his sins through the generosity of his will: his estate was divvied up equally between his children, wife, and friends and left no one dissatisfied. After most of his wooden statues were knocked loose by a strong gale of wind in 1815, they were sold off at auction. Once purchased by Dexter for $2,000 each, they fetched disparaging sums — between 50 cents and $5.

In a final act by society to omit Dexter from its affairs, Newburyport’s Board of Health rejected his request to be buried in the tomb he’d concocted years earlier, on the grounds that it wasn’t sanitary. Instead, the Lord was laid to rest in a quaint cemetery in the hills, where wheatgrass quickly engulfed his headstone.

***

Today, the few who are aware of Lord Dexter maintain split opinions on the man — some call him “grotesque and idiotic”, while others elevate him as a “genius.” In the Dictionary of American Biography, a collection of “great men,” author Francis Drake clarifies Dexter as a man who “lacked that kind of prudence which so frequently hides bad and sets off good qualities.”

Still, there seems to be something honorable in Dexter’s utter disregard for normalcy: though he endlessly sought recognition by the upper class, he never ceased going about things in his own strange way.

“Dexter had a way of his own, which he disdained to copy or suffer to be copied,” wrote biographer Samuel Knapp, a few decades after Dexter’s passing. “In short, he was a living exception to all general rules, and a living contradiction to all maxims of human wisdom.”

![]()

This post was written by Zachary Crockett. You can follow him on Twitter here.

For more stories about quirky people, check out our new book! → Hipster Business Models