In the 1940s, comic books experienced a golden age. The archetype for the superhero — a big, muscular, white do-gooder — was set in place by Superman (1938), and followed by a lineage of similar characters like Batman, Captain America, and Captain Marvel. Fueled by wartime patriotism, these superheroes were tropes for Western benevolence; they battled the Nazis and the Japanese, and fought to preserve America’s dominance on an international level.

Comic books emerged as a legitimate mainstream art form and the industry exploded; millions of copies were sold per issue, and they not only became a rhetoric for the World Ward II landscape, but a guiding voice for America’s youth. But early comics, touted for telling tales of “good triumphing over evil,” were also riddled with racial stereotypes, insensitive dialogues, and portrayals of Eurocentric ideals — typically through the role of the sidekick.

Wherever there is a hero, there is a sidekick; for thousands of years, these subordinates have graced the pages of literature. Biblically, for instance, Moses’ brother Aaron serves as a sidekick: while he accomplishes several amazing feats and is beloved, he’s also a bumbling bonehead who makes grave mistakes and is a martyr for moral lessons. This is typical: often, a sidekick acts as a subdued, under-spoken counterpoint to the story’s hero.

In comic book form, the sidekick dates back to the inception of the genre, where the role was often used as a basis for comic relief. While several respectable sidekicks did exist in the 1940s (ie. Batman’s Robin), they were largely lovable fools who sought nothing more than to please their masters — the superheroes they served.

As such, sidekicks during the era were sometimes written as minorities — largely Asians and African-Americans — who were generally treated as inferiors in society. Late 19th century Jim Crow ideals still pervaded America: blacks were segregated, and seen as sub-equals. At the same time, the onset of World War II rejuvenated racist ideologies toward Asians; after the attack of Pearl Harbor in 1941, all Asians became targets for humiliation and comedic relief in the media.

While minorities were excluded as superheroes, they did play a role in comic books as subordinated sidekicks — often as the worst stereotypes.

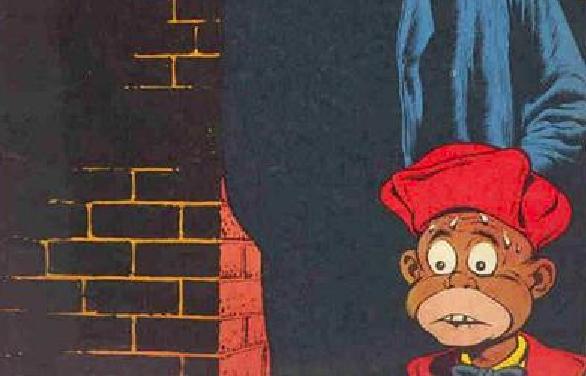

Wing (The Crimson Avenger)

In an October 1938 issue of Detective Comics (later DC Comics), the Crimson Avenger was debuted. A masked crime fighter, the pre-Batman character fit the superhero trope: dominant chin, angular jaw, and a subservient sidekick who did his dirty work. In this case, the sidekick was a racialized Chinese chauffeur named Wing.

At first, Wing’s appearances in Detective Comics were limited — he was hardly ever seen — and the writers were somewhat graceful in his portrayal. He was usually in the heat of battle with an enemy, and carried with him the contrived ideals of a “model minority:” loyalty, unquestioning faith, and an impermeable work ethic. Then, just before 1940, Wing was re-branded.

Suddenly, he appeared in a garish yellow onesie, equipped with a “shark fin,” and ill-fitting red shorts. Consistent with racist Asian-American media representations at the time, his features were highly characterized: his teeth — in need of serious dental manicuring — were splayed out like a deck of cards; his body was small and thin, juxtaposed beside the avenger’s bulky frame. Though he perennially wore an open face-mask, his eyes were so slanted they were not even visible (the Avenger, who wears the same mask, has clear, round eyes).

Whereas he was once a distinguished grown man, he was now infantilized and dumbed down. His dialogue was “ching-chonged:” he lost his ability to pronounce certain syllables, and spoke in a highly stereotypical, oft-uneducated manner. Before, he’d referred to his boss as “Crimson Avenger;” this morphed into “Mist’ Climson.” Often, Wing’s dialogues degenerated into an incomprehensible mess — “Lemembel, gills! No folget buy US Wal Bonds! And when get plegnant, thlow the gill ones away!” — and the reader (in the 1940s, presumably a teen boy) would have to work hard just to discern what the character was saying.

Wing’s roots stemmed from a lineage of racialized Asian characters in comics — most notably Kato, sidekick of public radio’s The Green Hornet series. Kato, represented as a Japanese-American, premiered in 1936, and enjoyed a few years as an “honorable sidekick.” Then, following the invasion of China by the Empire of Japan in 1939, the character’s name was rescinded; he was henceforth known solely as “faithful valet,” and felled his enemies with a swift karate chop.

In The New 52, a 2011 revamp of old DC Comics, Wing is reborn as a young Asian-American cameraman. Respectable, well-spoken, and attractive, he is a far cry from 1940s Wing. To ice their political correctness cake, DC also racebends The Crimson Avenger into an African-American woman.

Chop-Chop (Blackhawk)

Will Eisner was one of the early pioneers of the comic book genre; in 1941, with Quality Comics, he penned Blackhawk, which went on outsell every comic but Superman. Billed as “stories of the Army and Navy” and “a modern version of the Robin Hood story,” the comic followed the exploits of World War II pilot Blackhawk and his troupe of seven fighters.

Several years into the comic’s run, Chop-Chop made his debut as Blackhawk’s incapable, comic sidekick. Obese, yellow-skinned, buck-toothed, and short, Chop-Chop’s depiction, like Wing’s, bore semblance to most Asian representations in American media during the period. To cap off his unflattering aesthetics, he was drawn with a bald head (save for a small, red-bowed ponytail), spoke in severely broken English, and was dressed in colorful “traditional” garb.

Though he possessed ingenuity and resourcefulness (he even built his own plane in one strip), he never ascended his subordinate role, and was relegated to Blackhawk’s co-pilot in every mission. Instead of a gun, grenade, or more modern weapon, he was depicted waving around a cleaver, and appeared more prepared to butcher a pig than go into battle.

It took Blackhawk ten years to finally acknowledge Chop-Chop as a full member of the team, and by the mid-50s, the artists finally began drawing him in the same style as the other characters (he’d previously been far more “cartoonish”); his traditional garb is exchanged for the blue-and-black uniform worn by his partners. By the 1980s, opinions towards Asian-Americans had shifted, and Chop-Chop was storyboarded as an entirely different man. He is no longer complacent, and now seeks recognition for his feats, and equal treatment. In return, his friends (read: the comic book authors) bestow him with a “grand ceremony” to make up for his past maltreatment.

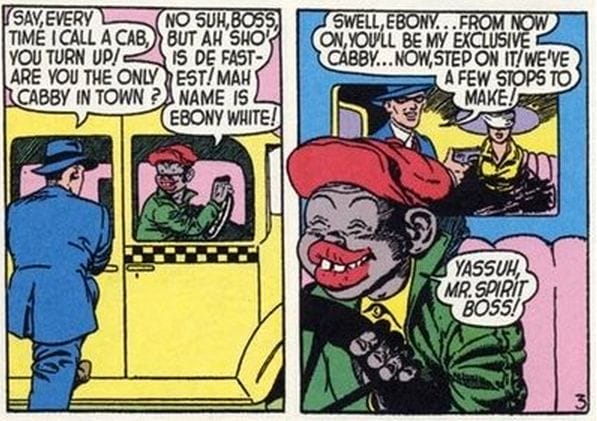

Ebony White (The Spirit)

The Spirit, also penned by Will Eisner, was known for its groundbreaking content and form. The strip’s title character, Denny Colt, is a masked vigilante who fights crime in gritty New York City — much of which is based on 1940s noir movies and fiction. The comic is also remembered for its racist portrayal of the protagonist’s sidekick, Ebony White.

First appearing in print on June 2, 1940, Ebony White was a black taxi driver, and Colt’s accomplice; frequently, he maneuvered the superhero through dangerous situations at his own expense.

With large white eyes and thick, rotund lips, Ebony White resembles the stereotypical pickaninny: though he’s a grown man, he’s diminutive in stature and lacks intellectual development. His devout loyalty to The Spirit, in conjunction with his pun of a name, pins him as an excessively subservient “Uncle Tom” character. Despite White’s obviously exaggerated features and apish demeanor, Eisner didn’t receive much pushback against his character, as such representations were already so ingrained as a norm in society. His former manager, Marilyn Mercer elaborated on this in a 1966 New York Herald Tribune feature:

“Ebony never drew criticism from Negro groups (in fact, Eisner was commended by some for using him), perhaps because, although his speech pattern was early Minstrel Show, he himself derived from another literary tradition: he was a combination of Tom Sawyer and Penrod, with a touch of Horatio Alger hero, and color didn’t really come into it.”

Eisner himself later expressed nonchalance over the creation of Ebony White, admitting that while he was knowledgeable of his employment of racial stereotypes, that was just a product of the era, and was thus justified. “At the time, humor consisted of bad English and physical difference in identity,” he told the Time in 2003. “I attempted to depart from it by having a black character…who spoke proper English.”

Indeed, years later, when DC Comics rebooted The Spirit, Ebony White was resurrected as “a much more intelligent and streetwise character:” he’s well-read, well-spoken, and often carefully analyzes the minutia of details overlooked by the protagonist. At the same time, it is highly implied that he stole the taxi he drives, has no home, and is essentially a ne’er-do-well street thug.

Whitewash Jones (The Young Allies)

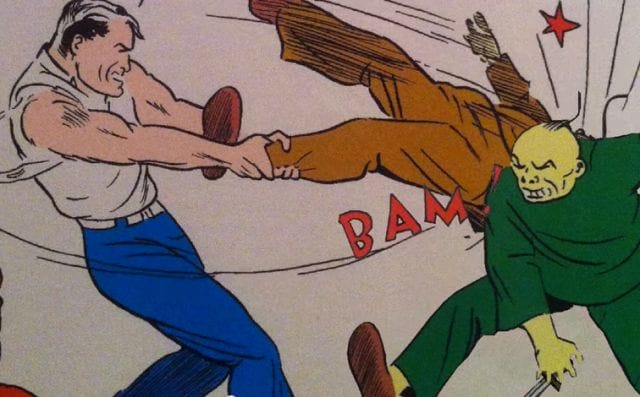

In December 1940 — a full year into World War II, and a year before the attack on Pearl Harbor — two young artists at Timely Comics (later Atlas Comics) created Captain America.

A “consciously political creation,” Captain America was intended to serve as an anti-axis power hero: the comic’s first cover pictured the protagonist punching Hitler in the face, and subsequent story lines pitted him up against Nazis, Japanese soldiers, and other perceived threats to the United States. The comic became so immensely popular, that the artists capitalized on it by producing a swing-off — “The Young Allies” — branded as a “multiracial group of patriotic kids” fighting the axis evil.

“Multiracial” was used quite generously: The Young Allies were composed of four friends — three of them white, and one black — but the dynamics of this team were highly problematic. While the three white friends were generally useful and pragmatic, the black character, “Whitewash Jones,” was portrayed as a bumbling, watermelon-loving dimwit.

As the three white characters were are sidekicks to other superheroes, Whitewash served as the “sidekick to a team of sidekicks” — the ultimate junior role. Each character was written with a special skill — one was an expert puncher, another a master inventor, and the third an intimidating presence — and then there was Whitewash, devoid of any redeeming qualities.

Drawn in a completely different style than his compatriots, Whitewash Jones, like Wing, was presented as a highly stylized, inhumane characterization of an African American male. Whitewash had massive protruding lips, prominent ears, and tiny eyes, and was often depicted wearing a straw hat (reminiscent of slave depictions in the 19th century). As comic book historian Darren R. Reid puts it, Whitewash was a “perfect celebration of racist iconography.”

The character’s dialogue only further enforced this. Since he lacked any clear directive, Whitewash took on the mantle of comic relief; his traits — inept, blundering, awkward, and cowardly — painted an image eerily similar to that of a pre-Civil War era depictions of African Americans. In Young Allies #1 (the series’ debut), Whitewash is seen bragging about his watermelon playing abilities:

Another clip features the gang in a graveyard, where Whitewash is spooked by the tombstones around him. “I ain’t goin’ in der,” he says, cowering with fear. “Ah just ‘membered — ah got run an er’rand for muh mommy!” A few frames later, he proclaims his undying love for America:

“I sho am glad ah lives in America — where dey ain’t no headhutin’! Yassuh! Ah sho glad dey ain’t no headless bodies around ol’ whitewash!”

Rife with deliberate misspellings and grammatical anomalies, Whitewash’s dialogue is a far cry from the pure, polite narratives of his blonde, blue eyed friend (above): “I am honored to make your acquaintance!”

And who were the creators of this unapologetically racist character? None other than Jack Kirby (co-creator of the Hulk, and X-Men), and Joe Simon (who’d go on to enjoy an illustrious career and be inducted into the Will Eisner Comic Book Hall of Fame). But they received some help along the way: Stan Lee, who’d later create spiderman, wrote much of Whitewash’s dialogue. All three men are legends today.

However egregious Whitewash’s representation was, it should be contextualized that the U.S. Military was segregated at the time; his mere presence in a troupe of white crime fighters could be viewed as progressive. But others claim that any attempt at equality is negated by the artists’ execution and approach.

In every modern history of Marvel Comics, Whitewash, along with any implication of racism, is completely overlooked. Jordan Raphael’s “Stan Lee and the Rise and Fall of the American Comic Book” barely mentions The Young Allies; Sean Howe’s “Marvel Comics: The Untold Story” entirely dismisses the topic. In 2009, Marvel re-wrote and revived the series in an attempt to “retroactively redeem” it, rather than acknowledging its hairy past. Whitewash was reborn as “Washington Carver Jones,” an “affluent, distinguished African-American”

Social Landscape

In the arena of 1940s comic books, no minority was the star. Instead, they filled a role they were more predisposed to in pre-Civil Rights America: that of the subordinate sidekick. In consciously writing in some of their characters this way, comic books — the literature of the “innocent” — propagated minorities as unequals. It wouldn’t be until the 1960s that the first African-American superhero emerged, but this came with its own set of issues: he was cast as the “Black Panther,” star of a series called Jungle Action. It was short-lived.

One could argue this was “just part of the times,” or that this type of imagery was pervasive in most American media at the time (wartime propaganda films, newspapers, magazines, Disney), but in a genre dominated by burly white men in tight-fitting costumes, the ostracization of minorities seems especially present.

Stan Lee, who helped create Whitewash’s character, later shared a different experience during the creation of his X-Men characters:

“It occurred to me that instead of them just being heroes that everybody admired, what if I made other people fear and suspect and actually hate them because they were different? I loved that idea; it not only made them different, but it was a good metaphor for what was happening with the civil rights movement in the country at that time.”

But the characters we see here are not made differently with the intention of scoring the admiration of Americans. Rather, the creation of the comic book sidekick — a weak jester foil with limited redeeming qualities — left an opening for racial minorities to be included, but in a way that indulged the worst racial stereotypes of the time.

This post was written by Zachary Crockett. Follow him on Twitter here, or Google Plus here.