United Nations peacekeepers want a raise. Or, more specifically, the countries that provide them do. Since the early 1990s, the price of a UN peacekeeper – the amount the UN pays countries that send soldiers abroad to staff peacekeeping missions – has remained steady at roughly $1,028 per month.

In the early nineties, the most wealthy and powerful countries in the UN sent their troops abroad to serve as peacekeepers. American, French, and British troops formed the core of peacekeeping missions. But whereas peacekeepers were once sent to act as a buffer between clearly separated armies with their consent, missions from the nineties to today involve decentralized conflicts where consent is tricky.

The dangers of these missions, in which peacekeepers can be seen as unwanted foreigners, drove wealthy, Western countries out of the peacekeeping business. The backlash against the deaths of American troops fighting as peacekeepers in Somalia, for example, as immortalized in the film “Black Hawk Down,” led to a system in which the wealthy countries of the Security Council design peacekeeping missions and then pay poor countries to provide the soldiers. Foreign Policy reports:

“While there are exceptions, U.N. peacekeeping is an activity mostly paid for by the rich world and carried out by troops from poorer states. The leading troop contributing states (TCCs) are Bangladesh, Pakistan, India, Ethiopia, Nigeria, and Rwanda. The top funders are the United States, Japan, Britain, Germany, France, and Italy. Combined, these countries cover well over 50 percent of the peacekeeping tab, while offering fewer troops than diminutive Jordan. The United States alone pays 27 percent but provides a grand total of 109 peacekeepers.”

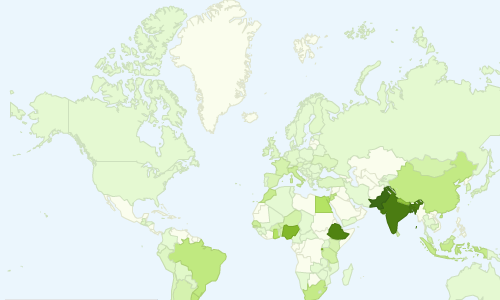

Largest troop contributors to peacekeeping missions in dark green. Source: United Nations Peacekeeping.

Reports of peacekeepers standing by as battles or massacres occur within miles of them in places like Congo and Sudan can be traced to the mercenary aspect of peacekeeping missions. Many governments send their troops without proper equipment, pocketing the UN funds intended for the purchase of arms, radios, and vehicles. States sending troops also often place restrictions on their use, so they cannot respond to active fights or enter dangerous environments. And troops whose governments are merely collecting pay, and do not have a strong interest in the peacekeeping mission, have no incentive to do their job well and no reason to risk their life.

The UN recently approved a 6.75% rise in the compensation for countries contributing peacekeepers, bonuses for taking on risky missions, and reforms to address countries pocketing the money meant to equip their troops. But as the states contributing the most troops are (with a few exceptions like India) not very democratic, outsourcing the risk to peacekeepers’ lives to poor and less accountable states still has a thorny moral logic. And with peacekeeping countries still primarily motivated by money, not results, no one should be surprised to hear more reports of peackeepers watching violence flare up in the future.

This post was written by Alex Mayyasi. Follow him on Twitter here or Google Plus. To get occasional notifications when we write blog posts, sign up for our email list.