Photo by Miikka H

*****

If someone told you that veggie burgers are the future of food, you’d probably panic.

To burger-lovers, a veggie burger is a rubbery imitation of the real thing. While cooking show hosts and grill aficionados spend months searching out the best burgers, rankings of the best veggie burgers can read more like survival guides that identify edible options. For every article that legitimately praises veggie burgers, other laudatory articles with titles like “4 Veggie Burgers that Don’t Suck” acknowledge its poor reputation.

But even if you don’t like veggie burgers, it’s worth considering the veggie burger principle: the value of disguising vegetables as an all-American comfort food.

Thirty five percent of Americans are obese, and that stunning fact has led to countless efforts to improve our diets. Congress passed standards for healthier school lunches; Michael Bloomberg tried to ban the sale of giant cups of soda during his tenure as mayor of New York; and Michelle Obama has appeared on Sesame Street to talk fruits and vegetables. The trend toward healthy eating has led not just to more farmers markets and Whole Foods, but to the head chef of McDonald’s using the words “healthy” and “natural.”

Changing behavior, however, is hard, and none of these efforts copy what author Charles Duhigg calls “the only government program ever to cause a lasting change in the American diet.”

That government program influenced how Americans ate during World War II, when changing eating habits was crucial to the war effort. And if we follow its precepts, a healthier American diet may focus less on community gardens and kale salads than on making health food look and taste passably like the foods that are making us fat today.

In other words, follow the veggie burger principle.

The Army-Approved Meatloaf of World War II

“Meats and fats are just as much munitions in this war,” former president Herbert Hoover wrote in 1943, “as are tanks and aeroplanes.”

At the time, World War II had disrupted food supplies, and the U.S. government’s priority was feeding American, Russian, and British troops. As war planners sent most of the country’s steaks, cutlets, and chicken breasts overseas, they worried about protein shortages in the United States.

As a potential solution, the government wanted Americans to eat all the unrationed meat that wasn’t set aside for the military: “liver sausage, liver, tongue, hearts, kidneys, sweetbreads, tripe, brains, pork feet, and ox tails.” But most Americans did not know how to prepare these cuts of meat and refused to eat them. For this reason, at the urging of the Department of Defense, the newly created Committee on Food Habits studied how to get Americans to eat the unpopular, unfamiliar fare.

Over the course of more than 200 studies and experiments, the Committee found that discussions about the benefits of these organ meats worked better than lectures, and that associating liver and ox tail with patriotic sacrifice helped upper and middle class Americans accept foods that they saw as beneath their social standing.

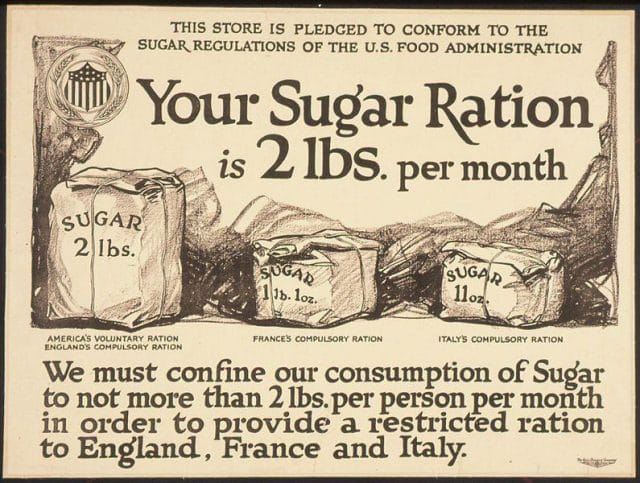

During the world wars food habits were a matter of national security. (This is from World War I.) Photo credit: US Food Administration, National Archives and Records Administration

But most of all, the Committee learned to disguise unpopular foods by making their preparation, taste, and appearance seem familiar. “Soon, housewives were receiving mailers from the government telling them ‘every husband will cheer for steak and kidney pie,’” writes Charles Duhigg in his book The Power of Habit. “Butchers started handing out recipes that explained how to slip liver into meatloaf.”

This worked with unfamiliar vegetables too. When American troops refused to eat fresh cabbage, cooks “chopped and boiled the dish until it looked like every other vegetable on a soldier’s tray – and the troops ate it without complaint.”

World War II ended earlier than the war planners expected, which meant the promotion of organ meat did not go on very long. Yet even in a short time—by teaching Americans how to slip unfamiliar cuts of meat into favorite dishes, or how to prepare them so they resembled and tasted like the choice cuts people loved—the Committee dramatically changed eating habits.

Sales of many of the once unwanted meats increased 33% or 50%. “Kidney had become a staple at dinner,” Duhigg notes. “Liver was for special occasions.” In a modern paper reviewing the research of the Committee on Food Habits, celebrated nutrition expert Brian Wansink of Cornell describes its findings as “lost lessons” and an “exception” in the long history of failed nutrition programs.

Forty years later, the same method of disguise would be applied to America’s favorite dish: the hamburger.

The Invention of the Veggie Burger

When Gregory Sams invented the veggie burger in 1982, there is no indication that he knew about the Committee on Food Habits. There’s no sign that he’d read up on cooks slipping liver into meatloaf during World War II.

His creation, however, exemplifies the lesson of the government’s efforts to change Americans’ eating habits: the key to quick adoption is to make something new look and taste familiar.

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, Sams and his brother Craig ran the vegetarian restaurant SEED in London. The brothers were inspired by Japanese cuisine—their menu featured ingredients like sesame, seaweed, and miso—and it was a hippie mecca. John Lennon and Yoko Ono were regulars; they loved the carrot nituke dish.

Buoyed by the success of SEED, the brothers founded a health food company to sell vegetarian food commercially. But even with the aura of Yoko Ono and John Lennon, the company struggled financially. So in 1982, Greg Sams started working on a vegetarian burger in an effort to save the company.

It wasn’t easy for the nearly lifelong vegetarian to mimic the taste of a burger, but after 6 months, he arrived at a recipe that used sesame seeds, rolled oats, wheat protein, soy protein, dried onion, and dried tomato. After considering names that included the ‘no-cow burger’, the ‘earthburger’, and the ‘sesame burger’, he settled on the ‘VegeBurger’. Sams thought his VegeBurger “tasted really good.”

Not everyone agreed. In an article in The Observer, a journalist writing about the VegeBurger described its flavor as “agreeable, if a little bland.” As Sams has recounted, the members of his own company thought there was no market for a meatless burger, which at that point, was a food only known and made in small circles of vegetarians. Sams eventually started a new company to sell the VegeBurger.

Despite the skepticism, the product was a hit. The first run of VegeBurgers sold out, and in 1988, Sams sold 13 million burgers. The brothers’ carrot nituke, presumably, remained popular among the small minority of London’s psychedelic and hippy scene. Even Yoko Ono’s endorsement couldn’t compete with the appeal of a “pleasant if bland” faux burger.

The Veggie Burger Principle

If you know where to look, you can find many examples of the veggie burger principle being used to introduce healthy, novel foods by disguising them as familiar favorites.

It’s the idea behind eggplant parmesan and kale chips. It’s why food entrepreneurs who want people to eat crickets—a nutritious protein with a lower carbon footprint than pork, chicken, or beef—are making cricket flour and cricket energy bars.

The co-founder of Veggie Grill, a fast-casual vegan restaurant that looks more like Chipotle and Middle America than a hippy paradise, also discovered the concept when trying to figure out how to make “wholesome fast food.” When T.K. Pillan visited healthy restaurants, he was impressed by what could be done with plant proteins. When he took friends to those restaurants, however, they said they liked the flavors, but not the style and atmosphere.

“That was our ‘a-ha!’ moment,” Pillan has said. “We decided we needed to make it fun, friendly, and approachable. We needed to make [plant-based proteins] into burgers and salads and American comfort food, things people already liked.” Veggie Grill, which now has 18+ locations and $20 million in funding, serves healthy, meatless takes on buffalo wings, chicken sandwiches, and, of course, cheeseburgers.

Similarly, Amy’s Drive Thru in Marin, California, sells what it describes as healthy, vegetarian fast food by looking like an all-American burger joint. The prototypical meal is a double patty (vegetarian) burger, fries, and a shake. It had a line out the door on opening day, and Yelp reviewers describe Amy’s burgers and fries as better than those down the street at In-n-Out Burger.

That said, neither vegetarian food nor food that is marketed as health food is guaranteed to be healthy, and the veggie burger principle can be applied to new, unhealthy foods just as easily as nutritious ones. Depending on the recipe and preparation, veggie burgers can range from healthy vegetables in disguise to just another processed product. Many foods that obey the veggie burger principle are made in labs, and that probably concerns advocates of better eating.

After all, it’s food labs that created sugary cereals, oh-so-crunchy chips, and all the other addictive, fattening foods that helped create a global obesity epidemic. Amy’s Drive Thru could use the fast food franchise model to sell tasty, healthy, and convenient food at scale. But it could be following the playbook of General Mills and Yoplait, which took advantage of yogurt’s status as a health food to sell billions of dollars of yogurt that is as sugary as a dessert.

This is why so many reformers advocate a diet of “real food” and ingredients you can pronounce. Food companies abuse our perceptions of healthy food and dump sugar even into savory products like tomato sauce, so visiting farmers markets, cooking your own meals, and eating at farm-to-table restaurants can feel like the only way to avoid unhealthy food.

But that’s a long term play, and people are dying now.

One in three American adults are obese, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. That’s over 75 million people, and the resulting health problems—heart disease, diabetes, stroke, and some cancers—cost the country an estimated $147 billion each year in additional medical bills and rank among the leading causes of preventable death.

The situation is nearly as dire abroad. Japan is the world’s only wealthy country with an obesity rate below 10%, and obesity rates rise when countries develop. Fifty years ago, 15 to 30 million Chinese died of hunger; in 2014, the Wall Street Journal reported that “Chinese kids are almost as fat as Americans.”

A world full of people with the time, money, and know-how to prepare wholesome meals every day is a great goal. But people want convenient meals, cheap fare, and the foods they grew up with.

If America wants to lose its top spot as the world leader in obesity, the veggie burger principle might be our best bet.

![]()

In our next post, we take a look at dishes that were once in vogue, but are no longer on modern menus. To get notified when we post it → join our email list.

This post was written by Alex Mayyasi. You can follow him on Twitter at @amayyasi.