Let’s say you get into an accident and an ambulance arrives to take you to the hospital. It could be for a life threatening injury, or more of a precaution. A few weeks later, a bill arrives for ambulance services. How much should you expect to pay?

The correct answer is that you never really know. Charges for ambulance transportation vary dramatically across the U.S. and from provider to provider. In Monterey County, California, the average minimum charge for basic life support (BLS) ambulance transportation is $2,206. A few hours away in Mendocino County, the average is just $575. To make matters worse, as this author recently learned, health insurance may only cover a fraction of the charge if the provider is out-of-network. In an emergency situation, patients are unlikely to compare ambulance prices or find an in-network provider, which leaves many suffering from sticker shock.

That’s exactly what happened to Robin Spring of Corralitos, California. Spring called 911 after becoming short of breath and was taken to the hospital in an ambulance. She later received a bill for $2,288. Citing the fact that the ambulance was out-of-network, her insurance covered just $750, leaving Spring with a balance of $1,538. But there were no in-network ambulance companies in Santa Cruz county, where Spring lived. “It made me furious,” Spring said. “I thought, ‘This is a real setup.'”

Only one ambulance provider serves Austin, Texas, where this author lives. Austin-Travis County EMS (ATCEMS) is the exclusive provider of 911 ground response and transport in the county. ATCEMS is a publicly funded organization and barred from entering into contracts with insurance companies. As a result, every ambulance in Travis County is, by definition, an out-of-network provider.

How did we end up with such a system?

Medicare rates for ambulance transportation across the country demonstrate the variance in cost. The range between providers in the same region or area – or between different customers based on their insurance situation – is even more dramatic.

In 1960, ambulance service was often provided by local police or fire departments that utilized trucks, highway patrol cars, or other vehicles. Funeral homes also stepped in as their vehicles were well suited for transporting individuals while lying down.

By the mid-1960s, two factors prompted the development of the modern EMS (emergency medical services) system. First, improved life support techniques that could be performed in the field created the opportunity for more advanced pre-hospital emergency care. Second, with more people on the road, higher incidence of traffic accidents created a larger demand for ambulances. These factors prompted a push towards creating a larger and more systemized emergency medical service. What was once a primarily municipal system became a much more complex system involving local, regional, state, and federal players.

The reforms of the 1960s brought about a much higher quality of EMS, but they also resulted in a much more fractured regulatory environment for ambulance companies. Today, in many municipalities, the local Fire Department continues to provide EMS. Elsewhere, EMS operates at the county level. Some EMS providers rely heavily on volunteer EMTs (emergency medical technicians) while others employ a full staff of paid paramedics. In other cities, the government contracts out EMS to private companies or the ambulance system operates as a hybrid.

Los Angeles County, for instance, has a permitting process for private companies, but sets a maximum billable charge for ambulance services within its jurisdiction. Each year, the amount is adjusted for inflation. Additionally, the county conducts a survey of other counties in California and may increase the maximum charge further if the rate in Los Angeles is below the state average. Most recently, the maximum charge was set at $1,033.50 for basic life support (BLS) and $1,444.75 for advanced life support (ALS).

On the other hand, San Francisco County utilizes a mix of public and private providers, but does not set a maximum charge. There are 6 licensed ambulance providers in San Francisco and charges can vary quite a bit from provider to provider. The Fire Department’s minimum charge for BLS and ALS transport is $1,642. In contrast, a private company quoted a minimum BLS charge of about $980. However, the charges can range based on the type of service (BLS vs. ALS, emergency vs. non-emergency) and whether transportation is required (an ambulance may assist a patient, but not need to take him or her to the hospital). San Francisco uses a priority system based on geography for dispatching emergency ambulances. Consequently, from a patient’s perspective, the quality and cost of the ambulance provider that responds is out of their hands.

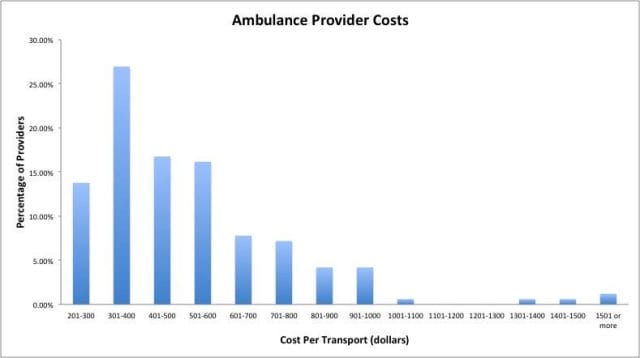

Underlying costs for ambulance providers explain some of this variance. According to a 2012 national GAO study, the median ambulance cost per transport for ambulance providers ranges from $224 to $2,204. The study identified several major factors that contribute to the wide range of costs including customer volume, percentage of non-emergency transports, level of government subsidies, and the local cost of practicing medicine.

A major factor behind high charges is that insurance reimbursements often do not reflect provider costs, leaving a small margin for ambulance companies. In 2010, the average Medicare payment was just 2% more than the average provider cost per transport. For many providers, the payment was less than the average cost per transport, meaning that the provider actually lost money transporting Medicare patients to the hospital. Insurance reimbursements, which are often based on Medicare fee schedules, may be even less. According to Robert E. O’Connor, chair of the Department of Emergency Medicine at the University of Virginia School of Medicine, in-network reimbursements often cover just 50 percent of the cost or a percentage of the Medicare reimbursement rate.

Since margins are thin for Medicare and in-network patients, ambulance providers often avoid negotiating contracts with insurance companies or charge out-of-network individuals significantly higher rates in order to compensate. “We try to participate, but sometimes plans come at us with rates that aren’t fair,” emergency physician Michael Gerardi told the Washington Post.

Many Americans with good insurance will not be overburdened by their ambulance bills. Medicare patients who meet their deductible typically pay 20% of the amount quoted by Medicare. Insured patients who take an in-network ambulance usually pay a fraction of the negotiated amount as well. But the system fails people who happen to take an out-of-network ambulance or don’t have insurance. In that case, the provider is free to charge any amount it sees fit, and the bills are often steep.

Patients who have insurance and means, but use an out-of-network provider, face the highest out-of-pocket costs. When the ambulance arrives, they have unknowingly entered into an arrangement in which their insurance will likely cover only a fraction of the charge, if any of the bill, leaving them on the hook for the balance. Maria Kinghorn of Utah faced this situation. Left with an $800 balance, she decided to pay up. “We didn’t want to have our credit ruined for $800,” she told Kaiser Health News.

Other patients may lack insurance coverage and be unable to pay their bill. “50 percent of the calls we go on we don’t get any reimbursement for,” says chief paramedic Josh Nultemeier of King American Ambulance in San Francisco. One estimate put the collection rate (the percentage of ambulance charges that are actually paid) in San Diego county at just 33%. When first responders respond to a call, they don’t know whether they’re picking up a customer who can pay or not.

Amanda Brewer, a working mother from Carrollton, Mississippi, who lacks health insurance, faced a struggle with medical bankruptcy after her son broke his femur in her backyard. The ambulance charge was $2,448.50. Though Brewer initially negotiated to pay the charge in installments, the collections agency demanded the payment in full several months later. The agency only relented when Brewer asked whether they’d prefer that she declare medical bankruptcy. But while Brewer avoided bankruptcy, many others do not. A recent study found that medical bills are the largest source of bankruptcies in the U.S.

A major component of the American health care debate is whether the ability of patients to shop around for the best deal among various providers will drive down costs. The fundamental problem with the economics of ambulance transport is that patients have almost no ability to make an informed choice.

When people need an ambulance, they’re usually not thinking about in-network benefits. In emergencies, the decision may be out of the patient’s control if a bystander calls 911 or if he or she is unconscious. And even when a patient is cost-conscious, there may be only one local provider or the decision may be made by the dispatch system. As the costs of America’s patchwork system vary dramatically, whether a patient receives a manageable bill or a crippling one is ultimately a matter of chance.

This post was written by contributor Alex Medearis. Follow him on Twitter here. To get occasional notifications when we write blog posts, sign up for our email list.