A victim of San Francisco’s Preparedness Day Parade bombing; Online Archive of California

On the afternoon of July 22, 1916, thousands of San Franciscans gathered along Market Street for what was advertised as the “grandest parade of the century.”

Nearly 100,000 people from all across the western states came to see the impressive procession of 51,329 marchers, 2,134 participating organizations, and 52 bands. Giddy, balloon-clutching children jumped with joy, parents bantered about the war raging overseas, and vendors slithered through the masses, peddling commemorative pins for a nickel. As fog horns bellowed from the bay, cheers and whistles echoed down Market Street. On this Saturday afternoon, spirits were high.

Then, a bomb exploded.

Hoards of concerned citizens scrambled for safety, children shrieked — not with joy, but terror — and the cavalcade came to an unceremonious halt. By the time the chaos had subsided, 10 lay dead. More than 40 others were left gravely wounded, including one young girl who “had her legs blown clear off.”

The incident would prove to be the deadliest act of terrorism in San Francisco history. Unbeknownst to the city’s residents, it would also result in a decades-long miscarriage of justice by police, prosecutors, and political figureheads.

This is the story of the Preparedness Day Bombing — a cautionary tale of not only terrorism, but the complete suspension of civil rights.

The Preparedness Movement

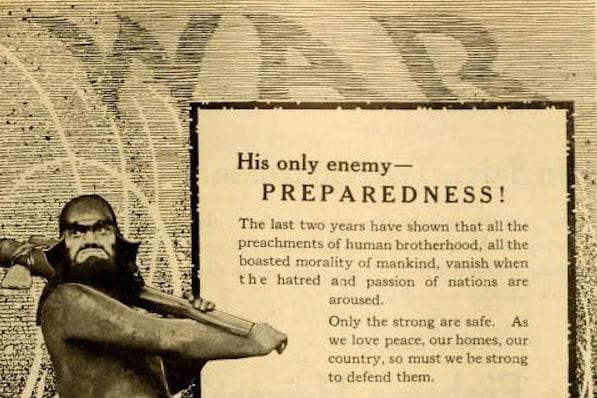

A U.S. Preparedness ad, 1916

Shortly after the outbreak of World War I, the United States made an effort to bolster its army. In 1915, ex-President Theodore Roosevelt launched the “Preparedness Movement,” a campaign that called for the “need to immediately build up strong naval and land forces for defensive purposes.” Backed by the nation’s most elite bankers, industrialists, and lawyers, it quickly gained steam.

On June 3, 1916 — a mere seven weeks prior to the San Francisco bombing — President Woodrow Wilson enacted the National Defense Act of 1916, authorizing the expansion of the Army by 175,000 men, and the National Guard by 450,000. Proponents of the act championed “economic strength and military muscle” over the myriad of national concerns that needed to be addressed; it soon became patently clear that the nation was bracing itself to enter the war.

To support these efforts and mobilize citizens, cities across the United States staged grand parades. In San Francisco, most people were anti-preparedness and isolationists (against foreign involvement); nonetheless, the city decided to participate.

In the midst of this, San Francisco also faced intense unrest. A small but potent minority of labor leaders and organizations strongly opposed the emerging war effort, and were none too pleased with the news of the parade. Throughout June of 1916, they disseminated eerily foreboding pamphlets to potential parade-goers, warning of their intentions to attack:

“We are going to use a little direct action on the 22nd [at the parade] to show that militarism can’t be forced on us and our children without a violent protest.”

To combat these threats, the city’s Chamber of Commerce organized a special Law and Order Committee — but in a time where terrorism wasn’t taken too seriously, plans for the parade moved forward.

Tragedy Strikes

Morale was high and patriotism abundant as the day of the parade approached.

A week before the event, the San Francisco Chronicle published a full-page picture of the “Goddess of Preparedness,” including a set of unintentionally foreboding instructions; in them, it was declared that the festivities would commence with the blasting of a “bomb” (likely, just a firecracker):

“San Francisco will shout a full-throated salute during the preparedness parade when the second bomb is fired, which will be the signal for the bands to play ‘Star Spangled Banner.’ When this signal is given, every whistle in the city will open its valve and shriek patriotically.”

San Francisco Chronicle, June 20, 1916 (two days before the bombing); LHM

According to plan, ceremonies commenced just after the “bomb” sound, at 1:40 PM on Saturday, July 22, 1916. Set to last 3.5 hours, it was, by all accounts, the largest parade the city had ever organized — and one of the largest in United States history.

But at 2:06 PM — less than 30 minutes into the parade — an unknown assailant left a suitcase packed with timed explosives and steel slugs on the sidewalk at the intersection of Steuart and Market streets, just minutes from the city’s famous Ferry Building.

Moments later, an actual bomb exploded.

Eight people close to the explosion were killed instantly; two more died of grave shrapnel wounds en route to the hospital. The sidewalk was “littered with bodies,” according to one recount — some 40 lay wounded in various states. And as the masses panicked and cleared Market Street, investigators frantically embarked on a hunt for the perpetrator.

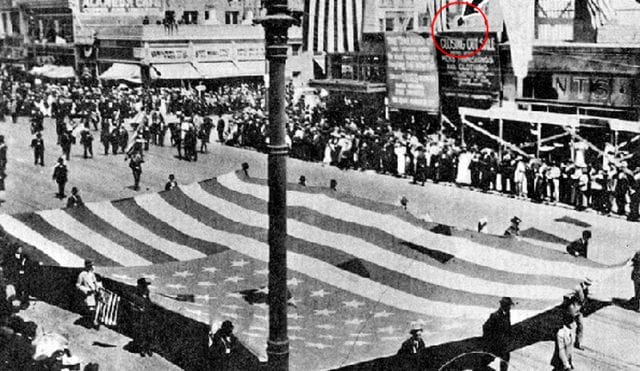

Crowds of San Franciscans gather around the site of the explosion

Investigators survey the scene of the bomb

Over the next four days, authorities honed their search to known San Francisco labor radicals — those who were anti-war and championed the Marxist belief that violence may be necessary to invoke social change.

The media joined in, encouraging citizens to be on the hunt for such “socialists.” Hearst-Pathe News, which had a stronghold on San Francisco’s media at the time, produced a brief, propaganda-esque film, insinuating that anarchists or communists were to blame. “Wake up San Francisco,” it beckoned, “and save our city from further disgrace!” Interposed with images of Labor party meetings, the words “anarchy,” “sedition,” and “lawlessness” flashed across the screen:

Almost instantly, two radicals — Thomas J. Mooney and his assistant, Warren Billings — were targeted for questioning. Both had long been tracked by the police for their involvement in various “socialist shenanigans:” Mooney for “conspiring to dynamite power lines” at a 1913 strike, and Billings for bringing dynamite on a train. Both had previously been cleared of all charges for lack of evidence, but investigators were constantly looking for a way to imprison them. They were, as described by one publication, “San Francisco’s most hunted radicals.”

Mooney was especially hated by police. The son of Irish immigrants, had spent a few years as an industrial worker before traveling to Europe and becoming an self-proclaimed socialist and labor leader. He eventually returned, settled in San Francisco, and published The Revolt, a widely-disseminated socialist paper; soon he’d become known for his radical tendencies. By the early 1900s, The Chicago Tribune had described him as “the foremost labor radical in San Francisco — an energetic organizer, an anarchist, a strike leader…and a militant pacifist.”

On what would turn out to be very little evidence, the city’s District Attorney, Charles Fickert, pegged them as the culprits.

On July 26 and 27, he had Mooney and Billings arrested, along with Mooney’s wife and two fellow trade-unionists — Israel Weinberg (a taxi driver by trade), and Edward Nolan, then-President of the Machinists’ Lodge.

San Francisco’s Sacco and Vanzetti

From the start, the process was horribly misconducted.

All five were arrested without warrants. Offered no explanation for their detainment, the suspects’ homes were then raided by Swanson and his task force. When a trace amount of powder was discovered in Nolan’s basement, it was instantly identified, with no ballistic testing, as saltpeter used to craft the parade bomb (later, it would be revealed that it was merely bath salt). The suspects were placed in solitary confinement, where they were denied all access to counsel for nearly a week.

Thomas Mooney, the radical labor leader, was treated to an especially hostile examination. Over the course of six days, he was interrogated relentlessly — despite asking for his attorney some forty-one times.

Meanwhile, a lynch mob mentality permeated San Francisco. For a long while, shop owners has resented the labor unionizers, who they claimed interfered with their ability to maintain “open shop,” or freedom from unions. When they caught news that Mooney — their worst enemy — was a suspect, they were more than eager to go along for the ride.

Mooney and his wife, Billings, Weinberg, and Nolan were corralled to a swift sentencing on August 1, 1916. They were not permitted to “clean themselves up,” and arrived, haggard, unshaven, and foul-smelling.

Still left without the right to counsel, they refused to testify on their own behalf.

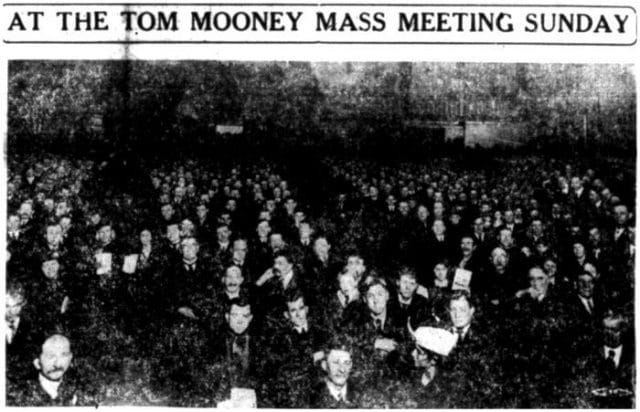

Crowds gather for Mooney’s pre-trial

Though hundreds of people had been at the intersection of Steuart and Market streets when the bomb exploded, the only witness the prosecutor could conjure to speak before the Grand Jury was a “ne’er-do-well waiter and drug addict” named John McDonald, whose recollections of the event were so garbled and inaccurate that he was called off the stand after only a few questions. Somehow, this was enough to convince the Grand Jury of the suspects’ involvement: each of the five were indicted with ten counts of murder.

Soon afterward, the cases against Mooney’s wife, Weinberg, and Nolan were dismissed: it became clear that the prosecutors were solely interested in taking down Mooney and Billings.

District Attorney Fickert, who led prosecution, soon formulated a theory of the bombing’s events: Mooney and Billings had met at Mooney’s residence, 721 Market Street (nearly a mile from the scene of the crime), and initially planned to drop the bomb from the building’s roof, but had changed their minds at the last minute; they then drove to down Market Street, and planted the bomb on the sidewalk. Any testimonies from witnesses that did not fit into this unfounded sequence of events were flat out ignored or dismissed by prosecutors.

Finally provided city-appointed defense attorneys, the two proceeded to separate trials.

Billings’ trial came first. In September 1916, following a very brief deliberation by the jury, he was found guilty of murder in the second degree and sentenced to life in prison. A motion for retrial was curtly dismissed, and with little publicity, he was sent to Folsom — the state’s most notorious prison.

Mooney’s initial trial, over the course of January and February of 1916, was a much grander affair. During the trial, many witnesses were called — all of whom were disreputable characters: a “tramp waiter,” a felon, a prostitute, and a cattle rancher from Oregon named Frank C. Oxman. Oxman, the “star witness,” claimed to have seen Mooney at the scene of the crime; quickly, it was declared that the entire trial “hinged on his statements.”

Though all of these testimonies were full of contradictions and didn’t seem to line up with one another, District Attorney Fickert championed them as the truth.

Just before the trial, the prosecutors had obtained a photograph supposedly showing Mooney on his roof at the time of the crime; fearing it would discredit their argument, they attempted to hide it. When the defense team learned of the photo’s existence, the prosecutors did everything in their power to deny access. A case study from the American Civil Liberties Union elaborates:

“When the defense demanded the photo, the prosecution claimed it was unable to produce it and furnished blurred enlargements. A large jeweler’s street clock appeared in the picture, but the time could not be read from the enlargement the prosecution furnished.”

A photo showing the figure of Mooney (red circle) atop his residence at 2:10 PM — five minutes before the bombing. The original, of much higher quality, was only released by prosecutors 30 years after the trial.

During Mooney’s trial, the photo was analyzed by experts and it was determined to have been taken at 2:01 PM — just five minutes prior to the bombing. As Market street was clogged with traffic on the day of the parade, it would’ve been impossible for Mooney to plant the bomb and make it back to his place that quickly. In light of this evidence, the prosecutors’ witnesses began flip-flopping their testimonies, claiming they’d seen Mooney earlier than previously stated.

Despite all of these inconsistencies, Mooney was convicted with first-degree murder and sentenced to death by hanging.

When a “Star Witness” is a Perjurer

Initially, Frank Oxman, the prosecution’s “star” witness, had donned the impression of a trusted witness in the courtroom, as noted by Judge Griffin, who presided over the case:

“His testimony was unshaken on cross examination, and his very appearance…was of a reputable and prosperous cattle dealer and landowner. This is no question but that he made a sound impression upon the jury and upon all those who listened to his story on the witness stand. He was the pivot around which all other evidence in the case revolved.”

But in April, two months after Mooney’s trial, it became startlingly clear that Oxman was a shady character. In a letter he’d written just before the initial proceedings, he’d bribed his friend from Illinois — a man he hadn’t seen in some twenty years — to travel out west and act as a witness (note: printed here in original form, including atrocious grammar and spelling):

“Cum to San Frico as a expurt wittness in a very important case. You will only hafto answer 3 or 4 questiones and I will post you on them. You will get mileage and all that a witness can draw — probly 100 in cleare so if you will come ans me quick in care of this hotel I will manage a balance.”

When the man heeded Oxman’s call and came to California, he soon discovered that Oxman wanted him to “perjure himself to convict an innocent man.” He refused, and in turn turned the letters over the Mooney’s lawyers, he swiftly appealed the convict’s sentence and demanded a retrial. The appeal was accepted, and a new case opened — this time to be tried before California’s Supreme Court.

Soon after, Oxman’s testimony that he’d seen Mooney commit the crime came under fire again. A couple from Sacramento, California – nearly 90 miles from San Francisco — came forward that they’d had Oxman as a guest in their home. On the day of the explosion, he’d left the capital on a train at 2:15 PM, and hadn’t arrived in Bay Area until 5:21 PM — three hours after the bombing. According to hospitality records, he’d then checked into a hotel at 5:30. The “star” witness apparently had never even been at the scene of the crime!

Frank C. Oxman, the prosecutors’ “star witness”

When Judge Griffin (who’d presided over the initial case) learned that Oxman had not only bribed witnesses, but flat-out lied under oath, he became enraged, and sent a letter to the state Attorney General: “Had these letters been before me at the time of the trial,” he wrote, “I would have unhesitantly [exonerated] Mooney.” In turn, the Attorney General assured Griffin that “justice would be subserved.”

But the State Supreme Court, limited by technicalities, made it clear they did not agree. “Manifestly, the court has no authority to consider these matters,” they responded. “There is no provision of law by which newly discovered evidence may be presented to this court in the first instance.” Mooney’s lawyers were also tied up: “statutory restrictions” required that new evidence be presented within a “short time period” — and that had expired.

Only the Governor could pardon Mooney, and he was wholly uninterested in doing so.

In the midst of Mooney’s legal battle, Oxman faced his own trial — for both subordination and perjury — and was embraced much more favorably by the court. District Attorney Fickert, who’d reigned over the Mooney trial and had commandeered Oxman and other witnesses, paid for the man’s defense. In court, Oxman argued there had been another page in the letter in which he’d told his friend not to come up unless he’d actually been at the bombing (ostensibly another lie under oath).

By all accounts, Fickert had “whitewashed” and bribed the jury: Oxman was promptly acquitted, and Fickert himself was commended by the jury for his “exceptional ability to bring justice to light.”

Despite evidence of a clearly tainted trial, Mooney still faced death. Labor radicals around the United States grew increasingly agitated, and organized a series of protests demanding his release:

Labor protestors line the streets of San Francisco in defense of Mooney and Billings.

The Iron Molders’ Union of Seattle protests Mooney’s imprisonment

Throughout the summer of 1917, hundreds of mass meetings, protests were organized. Major unions — the Machinists’ Lodge, the Iron Molders’ Association, and United Steelworkers — chose to strike, halting a large sector of the economy. Of 240 big unions outside of industrial centers, 220 participated in Mooney’s cause.

In San Francisco, citizens became aware of District Attorney Fickert’s shady involvement — both in the trials of Mooney and Oxman — and began to petition for his removal from office. The efforts did not pay off; in December of 1917, Fickert was re-elected. When several non-lethal explosions were detonated in protest, Mooney delivered a directive from his San Quentin prison cell: “Bombs will NOT benefit my cause,” he told labor activists, “but hurt it beyond measure.”

The case even spread internationally. Russia, at the time going through a period of revolution under the leadership of socialist Alexander Kerensky, took great pity on Mooney’s plight. Before the Russian U.S. Embassy, mass demonstrations took place, and the case made headlines across the world.

At this point, sensing a dangerous uprising, U.S. President Woodrow Wilson took matters into his own hands. Toward the tail end of 1917, he formed what he called a “Mediation Commission,” headed by Secretary of Labor William B. Wilson, and sent the team to San Francisco to investigate the case.

“There can be no doubt that Mooney was registered as a labor agitator of malevolence by the public officials of San Francisco,” reported Wilson, “and that they undoubtedly ‘sought’ to get him.” Wilson continued, noting “the dubious character of the witnesses,” and the overall lack of justice in the trial. In light of this report, President Wilson ordered that California’s Governor, WIlliam Stephens, postpone Mooney’s execution.

For nearly a year, Stephens dilly-dallied, and Mooney’s execution grew more imminent. Finally, on November 28, 1918, after multiple curt telegrams directly from the President, Stephens upheld his “duty of justice” of Governor — but Mooney’s sentence was merely commuted from death to life imprisonment, and his impending Supreme Court case was dismissed.

The Terror of Injustice

Thomas Mooney being interviewed by a reporter in a staged photo, late 1930s

For the next 22 years, Thomas Mooney and his assistant, Warren Billings — both innocent men — sat rotting in prison.

Over two decades, Mooney submitted dozens of petitions for a retrial, but they were of no use: under legal constraints, the only means by which he could be cleared of his sentence was a pardon from the Governor, or the President. Governor Stephens, who was reluctant to merely commute the man’s sentence in the first place — even with orders from the POTUS — wholly ignored his requests.

In 1919, John B. Densmore, a special agent of the Department of Labor, decided to take the case into his own hands. Without the authorities’ permission, he conducted a secret investigation of the case by placing a dictaphone (early recording device) in the office of District Attorney Fickert. What he revealed, in an interview with the Times, was appalling:

“The plain truth is there is nothing about the case to produce a feeling of confidence that the dignity and majesty of the law have been upheld. There is nowhere anything resembling consistency…manipulation and perjury are rampant. This is a total absence of anything that looks like a genuine effort.”

The new evidence did not entice Governor Stephens to act. Friend Richardson, who succeeded Stephens in 1923, likewise had no sympathy for Mooney — even when incredibly shady information regarding Mooney’s trial came to light.

In a 1926 report, it was revealed that another witness in the case, Mrs. Kidwell, had cut a deal with police: she’d testified against Mooney (with no knowledge of the day’s events), in exchange for a promise to release her imprisoned husband. “You know I am needed as a witness,” she’d written in a letter to her lover, “and they are helping me by getting you out.” Estelle Smith, another witness, admitted that she’d been ordered to “rehearse” her perjury by prosecutors under the threat of imprisonment for prostitution. A third witness, Mrs. Edeau, later admitted that only her “astral,” or spiritual, body had been present at the parade; she was later deemed mentally unstable by the state.

Evidence of perjury was so abundant and obvious, that Judge Griffin, who’d presided over the initial case nearly a decade prior, called it “the worst abuse of justice” he’d ever seen. In a statement, he discredited every single witness’s testimony:

“Damned near every witness who testified [against Mooney] before me was perjurious or mistaken. Estelle Smith has admitted her testimony was false. The Edeaus were completely discredited. Oxman [the ‘star witness’] is completely out of the case. John McDonald has since sworn…that he knew nothing about the crime.”

Still, Governor Richardson did not act, and Mooney continued to serve his life sentence.

Justice — 22 Years Late

Thomas Mooney smiles upon his release

By 1937, a succession of five California Governors had refused to review Mooney’s case. He was at the end of his wits. It was a “Dickensian nightmare,” the San Francisco Chronicle wrote of his plight, “one of the lowest points in the history of California law.”

Finally, When Governor Culbert Olson assumed office in January 1939, Mooney was granted justice.

“I am impressed by the fact that many thousands of Californians still believe Mooney is guilty,” Olson told reporters. “I am also impressed by the fact that five of my predecessors have not pardoned him. A hearing was ordered for Mooney’s pardon. Before a packed court of nearly 500 people, the Governor asked if anyone objected. For a full thirty seconds, he stood in silence, scanning the quieted room: no one spoke. The state officials and prosecutors who’d tirelessly — and unjustly — fought against Mooney for more than twenty years were nowhere to be seen. (Charles Fickert, the District Attorney who’d so inappropriately fought for Mooney’s near life-long detention, had devolved into a drunken gambler, lost his savings, and passed away in a few years prior.)

Thomas Mooney’s family and supporters await the result of his pardoning

“I now hand to you, Tom Mooney,” said the Governor, “this full pardon.” Cheers erupted: for two minutes, the room presented Mooney with a standing ovation. As flashbulbs popped, Mooney’s wife, who’d been acquitted of the same charge decades before and had stood by her husband’s side all the while, burst into tears, and the two embraced.

Lifting his hand to the crowd, he addressed the court:

“Governor, I shall dedicate the rest of my life to work for the common good in the bond of democracy. Dark and sinister forces of Fascist reactionism are destroying the world. The present economics system is in a state of decay — not just here ,but throughout the world. I pledge my efforts to the work of the common good.”

Mooney, declared the New York Times, “was free at last.”

Lasting Significance

A mural at San Francisco’s Rincon Center depicts the bombing and Mooney’s unjust imprisonment (far right); painted by Anton Refregier

The first thing Thomas Mooney did was visit the grave of his mother, who’d passed away while he was imprisoned.

Then, wasting no time, Mooney turned his efforts to freeing his friend, Warren Billings, who’d also been wrongly imprisoned the whole time, but with less attention. After 22 years of unsuccessful appeals, this proved shockingly easy: since Mooney was pardoned, there was no longer any justification for holding Billings. He was released 10 months later.

In a symbolic gesture, Mooney then organized a parade up Market Street — the spot in San Francisco that the bombing had occurred decades before. He was accompanied by a fleet of a hundred longshoremen, as well as a troupe of labor unions; police and politicians were strictly forbidden from participating. As he trotted through the streets, he “thumbed his nose” at the Hearst building, the media corporation that had denigrated him relentlessly at the onset of his trial.

But Mooney’s time in prison had taken a toll on him. Now 59 years old, he suffered from jaundice, ulcers, and diabetes. While on a lecture tour around the city, he fainted and was carted to a San Francisco hospital. As his politics were too radical, the California Federation of Labor refused to raise funds for his medical bills.

In March 1942, just three years out of prison, he quietly passed away.

***

The real culprit behind the Preparedness Day Bombing is lost to time — but many speculate it was Alexander Berkman, a radical who’d been responsible for several prior bombings, had once laid out a plot to “blow up California,” and who’d suspiciously fled to his home city of New York a day after the parade. Authorities were never able to extradite him for questioning.

But one thing is certain: it wasn’t Thomas Mooney.

To many, Mooney was a martyr for social justice — a symbol of “class persecution,” and a man who’d constantly pursued justice. His case — one of the first in the United States to determine that a verdict resulting from feigned evidence violates due process under the 14th Amendment — gave other who were wrongly accused hope.

“All I wanted,” he said, just before his death, “was to lift California of its shame.”

![]()

This post was written by Zachary Crockett; you can follow him on Twitter here.

To get occasional notifications when we write blog posts, please sign up for our email list.