“There is no way that people are going to want to sing ‘Play That Funky Music White Boy’ ten years from now.”

— Dr. Drax, American DJ Association president, at the 2015 Karaoke Summit

![]()

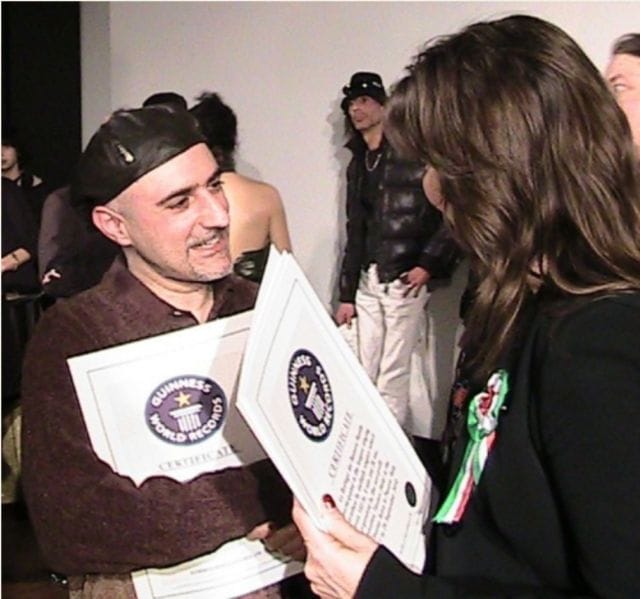

In September of 2011, somewhere around 4 AM at the Astra Cafe in Pesaro, Italy, things started to get weird for Leonardo Polverelli. His eyes were flickering open and closed. He heard noises that weren’t there. He was hallucinating. Basically he’d moved on to “a different kind of reality,” as he puts it. And he was only about halfway finished with the longest karaoke marathon in recorded history.

Luckily he was still able to hear the music. He could still read the lyrics. The cafe wait staff brought food and water during the 30 second breaks between songs. Friends applied wet towels to his face. Having read about this karaoke Pheidippides in the paper that morning, passersby popped in, cheered him on and made sure he was okay.

The spectacle raised money for charity, and in the end, the singer-songwriter polished off a four-day karaoke bender — 101 hours, 59 minutes and 15 seconds, to be exact — which covered 1,295 songs and still stands as the Guinness World Record.

There’s a funny distinction in here, though. Polverelli had originally intended to set the record for longest singing marathon. But imagine memorizing that many tunes. Bob Dylan and Madonna’s lovechild couldn’t do it. Polverelli had the lyrics handy, like anyone would. But when he sent Guinness the footage of his feat, the judges ruled that reading the lyrics classified the act as karaoke instead, not singing.

Even though that’s literally all karaoke is.

Oh Baby It’s a Wild World

Photo courtesy of Leonardo Polverelli

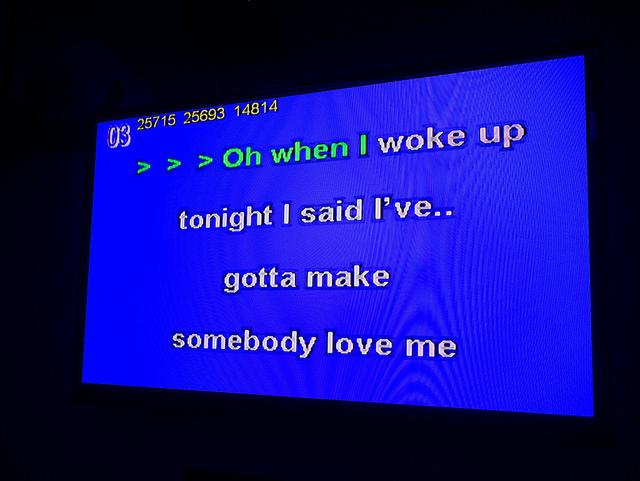

Karaoke tends to feel more like a game than an artform. You’re standing in front of a crowd, doing your best to recreate the vocals over a second rate version of your favorite song. The lyrics float up in old school Nintendo-esque typeface, changing color to indicate what to sing, as the room laughs and cheers you on. A step above sing-alongs, a step below a cover band. It occupies this funny place where whether you love it or hate it, you know not to take it too seriously.

But the businesses involved don’t feel that way.

Karaoke content producers like DigiTrax Entertainment produce those re-recorded songs and the accompanying videos. They get the rights from the songwriters and then license their recreations of the tracks to your favorite karaoke bars and KJs. Karaoke content producers need to get “mechanical rights” to re-record the song, but they must obtain a second set of rights called “sync rights,” which allow them to set a particular song to media, typically video. As David Grimes, a spokesperson for DigiTrax, explains, sync rights are attained on a track by track basis — not through blanket agreements. That’s in contrast to mechanical rights, which he says DigiTrax can do under bigger agreements. Sync rights are in place (partially) so owners are sure their music isn’t being set to porn or some weird ad promoting assault rifles. They also allow publishers to negotiate an additional — far juicier — deal should a big movie or television show want to use the song.

But attaining agreements on a song-by-song basis is time consuming. “We spend a large amount of time and effort securing license and compliance,” Grimes says.

So karaoke content producers become middlemen (as, one could argue, is any entity between the artist and the listener). And in an information supply chain, middlemen tend to feel the squeeze. With the way digital content distribution has been changing over the last decade, things have gotten much rougher for them — facing pressure both upstream and downstream from their niche in the market. Downstream, it’s become easy for hosts or venues to pirate karaoke tracks — robbing content producers of those licensing fees. And upstream, record companies have brought huge suits when they believe karaoke content producers themselves aren’t staying compliant with the terms of their agreements.

Hello From the Other Side

Photo: Rym DeCoster

Obviously there’s no discernible “origin” to the concept of karaoke. We’ve sang along with the music as long as we’ve had music.

But modern karaoke — with the machine and the graphically challenged lyrics — does have a recognized founder. In 1999 Time magazine listed Daisuke Inoue as one of the most influential Asians of the century for inventing the karaoke machine. Inoue and his friends devised eleven devices in 1971 and started leasing them around Kobe. It wasn’t long before his invention spread across the rest of Japan.

Perhaps slightly overstating the case, the magazine noted, “As much as Mao Zedong or Mohandas Gandhi changed Asian days, Inoue transformed its nights.” They justify this claim by noting that at the start of the 1900s, Japan and many Asian countries were seen as the rising military superpowers, set to take over the world. But the World Wars and the subsequent regional catastrophes ensured that wasn’t the case. As Time notes, Japan instead found its strength through business, and Inoue’s little creation ended up forming the social backbone of those important off-hours. Americans may get their business done on the golf course, but across the Pacific, that rule applies to the karaoke bar.

Time notes: “Thanks to [Japan’s] genius for dreaming up small machines that made convenience fun and fun convenient: Sony’s Walkman, the video games of Nintendo and Sega, Bandai’s Tamagotchi. Using technology to empower the little guy — suddenly anyone could listen to his own music in a crowded train, fax his handwriting across the globe or perform his own rendition of I Saw Mommy Kissing Santa Claus — has been the paradoxical contribution of a culture that outsiders too often associate with businesslike conformity.”

However it would take over two decades for Inous to get his real due as daddy of that fun machine. Five years after his recognition in Time, in a 2004 ceremony at Harvard University, the so-so drummer, who couldn’t even read music, was awarded an Ig Nobel Peace prize, dispensed by the non-Swedish humor outfit The Annals of Improbable Research, for “inventing karaoke” and “providing an entirely new way for people to learn to tolerate each other.”

“I had the dream to teach people to sing so I invented the machine,” he said during his acceptance in Sanders Theater, a venue that’s hosted Winston Churchill, Theodore Roosevelt, and Martin Luther King, Jr. “Now more than ever [he starts to sing] I want to teach the world to sing perfect harmony. Coca Cola! Let’s party! Thank you! Arigato!” To conclude the ceremony he sang “Can’t Take My Eyes Off You” with a band that included three actual Nobel Prize winning scientists, Dudley R. Herschbach (Chemistry), William Lipscomb (Chemistry) and Richard Roberts (Medicine).

But there’s a punchline with Inoue’s story. He didn’t patent his small machine. So the father of modern karaoke ended up earning next-to-nothing except gratitude for his contribution to the world with his fun, convenient little piece of intellectual property.

Sometimes Words Have Two Meanings

Photo: Karaoke World Championships

“Do we want an industry, yes or no?” Those are the ominous words of Dr. Drax, president of the American DJ Association. He made an appeal at Karaoke Summit 2015 in late October to all the karaoke jockeys (KJs), DJs and venues attending the conference or watching online. Recently Dr. Drax had witnessed too many KJs, DJs and venues arguing over intellectual property rights. The entire industry required some fundamental changes, he declared.

“Here’s the bottom line: if labels and songwriters don’t get rightfully compensated, karaoke will die,” he promised, noting the same fate would happen if content producers didn’t get their due. “Then we run into the situation of: the industry’s dead. It simply fades away. Because there is no way that people are going to want to sing Play That Funky Music White Boy ten years from now.”

Amen.

One of Dr. Drax’s chief concerns is DJs pirating karaoke content. Like most music, it’s easy to find free tracks or, in the case of videos, make your own. YouTube is full of how-tos. So a dive-bar DJ on a tight budget may choose that route instead of shelling out to a content creator. Not only are they skirting the licensing requirements, but they also skirt the performance fees, which venues are also required to pay, though this is typically a small amount.

But the only way anyone gets caught is if a representative from the songwriter or label that owns the track, or a trade organization like the American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers, happens to be in the bar that night. Not a high risk situation, though as Ars Technica points out, it can happen. Companies like DigiTrax and Karaoke Cloud are trying to deal with the drop in demand by offering Spotify-like subscription services, and time will tell how that works. (Spotify generates a lot of revenue, but, according to the Guardian, is still run at a heavy loss due to their own licensing burdens for streaming music, a different but related squeezing.)

Yet if these companies are getting rights to the songs, why do they alway have junior varsity music behind the vocals — and not the original tracks, minus the lyrics?

Because when you hear something on the radio or Spotify, there are two sets of rights governing that tune, though they can be owned by the same entity. Obtaining the rights to use to the original track requires signoff from both the record company and the songwriter. But karaoke companies only need the latter’s permission to re-record the song. Karaoke content producers then pay musicians to re-record the track elsewhere.

What’s In Your Head

Image: MarkScottAustinTX

If anything, karaoke isn’t dying, it’s gone pro. American Idol, The Voice and The X Factor are just a national karaoke competition. Games like Rock Band or Guitar Hero make anyone feel like they’re selling out Giants Stadium. Gameshow Killer Karaoke, which Vulture described as “either the epitome of trash TV or a surrealist masterpiece”, puts contestants into awful situations — dipped in a tank of snakes, a chest waxing, run through a maze of cacti with drunk goggles on — while nailing their favorite tunes. (Hosted by Steve-O from Jackass, of course.)

In late November representatives from 31 countries gathered in Singapore for the 2015 World Karaoke Championship. Elsaida Alerta of Canada and Muhammad Fairus bin Adam of Singapore took the women and men’s crowns. And plenty of smartphone apps and YouTube videos will help you make your own karaoke videos for having fun at home. (Take those creations to a bar for a “public performance” however, and you’ll need to pay the piper.)

But considering its popularity, believe it or not, there isn’t very much social science studying karaoke. A team of researchers in Japan presented a paper at a music conference in 2012 that investigated 185 (Japanese) mostly female college students’ participation, how karaoke induced mood change and the effect of going to karaoke, but not actually participating. (Some people just don’t do karaoke.) The short paper turns the obvious into delightful academic vernacular, finding that roughly three-quarters of participants “liked” karaoke, spent 2-3 hours at it when they went and typically did it with friends.

“These results suggest that college students in Japan prefer to go to karaoke to actively sing, occasionally going to karaoke with friends or people who have close relationships with them. They go to karaoke for amusement, to reduce stress, and socializing, and they feel less fatigue, depressive mood, and anxious mood from their active participation in singing.”

The results got a little more interesting with those who didn’t participate. Almost half of the participants stayed on the sidelines due to nerves, fatigue or because they simply don’t do karaoke. (We all know someone who takes this stance.) The non-singers, the researchers believe, go with the “principle aim of socializing, or for amusement and promoting communication with each other”. Yet the researchers conclude that in the end, sitting on the sidelines could be bad for you: “college students feel more fatigue, depressive mood, and anxious mood, and less refreshing mood.” But you can chat, have a drink and laugh at the spectacle. That’s good bonding. So they end up being ambivalent about whether sitting out is in fact bad for mental health. “There do seem to be some positive interpersonal effects to not actively singing, to maintain social relations with others rather than just to have a pleasant time at karaoke in private.”

Either way, just getting to the karaoke bar is probably a good thing: “In short, both forms of participation in karaoke can have beneficial effects.”

Of course, understanding all the rules that govern that participation may be hard to handle. But for now, rights holders believe it’s just like heaven.

![]()

Our next post investigates how the 1920s KKK was a giant, racist pyramid scheme.

To get notified when we post it → join our email list.

This post was written by Caleb Garling. You can follow him on Twitter at @calebgarling.