As a personification of the United States, Uncle Sam is at once beloved and detested.

The insistent cartoon — clad in stars and stripes and bearing great semblance to Abraham Lincoln — was, and to some extent still is, lauded as the alpha hero of America. Making appearances in everything from wartime propaganda to insurance ads, he is the heralded patriotic emblem of our country. As such, he’s also been the scapegoat for our financial woes. (Try making it through tax day without hearing “Uncle Sam took all my money!”)

But beyond his fictionalized grandeur, few realize that Uncle Sam was based on a real man who lived 200 years ago — a fairly unknown meat-packer from Massachusetts. An unlikely inspiration, his values and actions were far removed from those associated with his fictional counterpart.

Will the Real Uncle Sam Please Stand Up?

On September 13, 1766, a child named Samuel Wilson was born in Arlington, Massachusetts. The Wilsons, of Scottish descent, were one of the oldest families in the state; soon after Samuel’s birth, they migrated to New Hampshire in search of new opportunities. In 1781, at the ripe age of fifteen, Samuel packed his belongings and enlisted in the Revolutionary Army. Five years earlier, the war had begun; by the time Samuel joined, the revolutionaries (aided by the French) had largely succeeded in quelling British forces, and peace negotiations were in near sight.

Samuel was considered too weak to engage in combat, and was instead assigned to guard cattle, mend fences, and slaughter and package meat, a crucial role that fed a large contingency of servicemen. His post ended a mere six months later when Cornwallis surrendered at Yorktown, virtually guaranteeing the United States independence — but Samuel had taken advantage of the experience and learned a tremendous amount about meat distribution.

Several years later, Samuel embarked by foot to Troy, New York, with his brother. The two were some of the first pioneer settlers in the community, and quickly grew several successful businesses. Utilizing the exceptional clay native to the area, the brothers established themselves as New York’s preeminent brick-makers. Then, utilizing the capital they earned from their pursuit, the Wilsons leased a large lot and opened E&S Wilson — a slaughterhouse and meat packing business. The knowledge Samuel had acquired in the Revolutionary War paid off, and the two made a fortune.

One of the only known portraits of Samuel Wilson (c.1830s)

Reportedly, the residents of Troy immensely respected Samuel: he was a gentleman, a visionary, and invested in the community. Over time, he adopted the name “Uncle Sam” — an homage to his good-natured, kind demeanor. In 1808, he was elected to public office as an Oath Assessor; a mere four days later, he assumed the role of Road Commissioner, and was delegated the task of overseeing most of the town’s construction efforts.

When the War of 1812 began, Samuel was again called to action — this time in a major capacity. As his meat packing company was located along a dock (granting him river access), Samuel was given a contract to provide all of New York and New Jersey’s troops with rations for an entire year — some 2,000 barrels of pork and 3,000 barrels of beef. Samuel and his men stamped each barrel with a distinctive mark: “E&S – U.S.” It indicated that the meat came from E&S Wilson of the United States.

Wilson shipped the majority of these barrels to 6,000 soldiers stationed in Greenbush, New York, most of whom had grown up in Troy and knew Samuel. As the food came in, the soldiers immediately associated it with their hometown hero, “Uncle Sam.” The “U.S.” in Samuel’s stamps came to bear a double-meaning for soldiers and officials, as an abbreviation both for “Uncle Sam” and the “United States.” Back in Troy, a similar idea spread: when visitors on the docks inquired about the “U.S.” stamp and the identity of Uncle Sam, a seaman replied, “Why, Uncle Sam Wilson! It is he who is feeding the army.” The joke was repeated often in Troy, and spread to other provinces. Soon, all government provisions were referred to as “Uncle Sam’s.”

After the war, in 1816, one of these soldiers (under a pseudonym), wrote The Adventures of Uncle Sam: In Search After His Lost Honor; which featured the earliest written use of “Uncle Sam” as an allegory for the United States. In the book, Uncle Sam is an “army meat inspector” from Troy — undeniably, Samuel Wilson. This painted a glorified image of Samuel Wilson, and in doing so, also made him into something bigger — a representation of the entire nation:

“Uncle Sam offers you Liberty and peace, and as much happiness as you can stagger under….Uncle Sam is able to provide for all your wants; he offers you the invaluable privilege of managing your own affairs in your own way….Uncle Sam has been driven to take the bull by the horns; he is old enough to be very whimsical, but is no coward.”

American culture wrapped itself around Samuel Wilson; after the war, his nickname — Uncle Sam — spread and quickly became associated with a larger-than-life figure.

The Rise of the Modern Uncle Sam

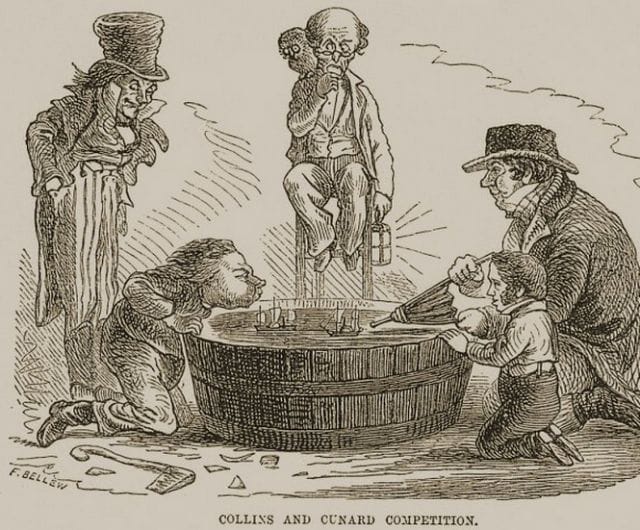

The first illustration of Uncle Sam shows John Bull (Britain’s national personification, far right) supporting the shipping industry while Sam idly stands by.

Before Uncle Sam, the United States was personified through several other fictional characters. “Columbia,” a stoic female figure, was coined by early American colonists in the 1730s as a way to give the country an “identity distinct from that of their British cousins on the other side of the ocean.” Another more popular character, “Brother Jonathan,” came into use during the Revolutionary War and was popular in the media throughout the mid to late 1800s. At the time of Uncle Sam’s first reference, Brother Jonathan was the uncontested personification of America.

In 1842, a weekly newspaper — Brother Johnson — was named after him and revealed him in illustrated form; Yankee Notions, a book published in 1852, used Brother Johnson to laud the “Yanks,” and he became a symbol widely used by New Englanders and Unionists. Weeks later, the first illustration of Uncle Sam appeared in the New York Lantern as part of a political cartoon by satirist Frank Bellew (see image above). In the thralls of the American Civil War (1861-65), two camps of supporters eventually arose — the “moderate Jonathans” (the Confederates), and the “radical Sams” (Unionists). Following the Union’s victory in the Civil War, Uncle Sam supplanted Brother Jonathan as the country’s “mascot.”

By the time of his death in 1854, Samuel Wilson had become something of a national celebrity, thanks to Bellew’s cartoon — but Uncle Sam would outlast his real-life origins and evolve into an icon of American folklore.

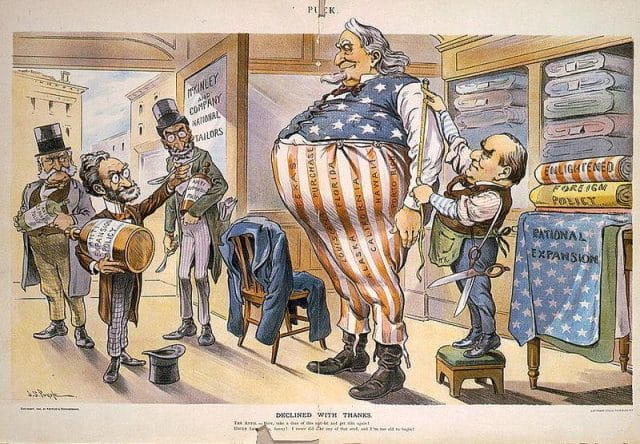

J.S. Pughe’s 1900 cartoon, “Declined With Thanks,” featuring a portly Uncle Sam

During the Civil War, the images of Uncle Sam and Brother Johnson widely varied, and were often conflated. It wasn’t until post-war that Uncle Sam received his modern-day makeover. In the late 1860s, cartoonist Thomas Nash (who is also responsible for illustrating Santa Claus, the Democratic Donkey, and the Republican Elephant) mocked up a drawing of a new Uncle Sam. Strikingly similar in appearance to Abraham Lincoln, Sam was tall, gangly, and goateed, and he was clad in a pin-striped suit and a star spangled top hat — a far cry from the original Samuel Wilson, who was clean shaven and dressed modestly.

The most iconic image of Uncle Sam was the brainchild of artist James Montgomery Flagg in 1917. In the now-famous World War I propaganda poster, a solemn Uncle Sam points directly at the viewer; beneath him, the text “I Want You For The U.S. Army” beckons young Army recruits. The image made its debut on the cover of Leslie’s Weekly and, over a two year period, sold over 4 million copies. The image was so widely distributed during the war that one German publication referred to America as “Samland.”

Flagg’s famous WWI image

The same ad was widely used during World War II, but Post-War, Uncle Sam devolved from a propaganda tool to an advertising gimmick, often appearing in real estate ads and on household product labels. He made a brief re-emergence during Vietnam, but a “strange mix of anti-establishment sentiment, the civil rights movement and the influences of a pop-art poster” softened his once-patriotic visage.

From 1970 onward, the famous “I Want You” poster concept was modified hundreds of times, both to publicize campaigns (a sexual revolution era poster has Uncle Sam asking “Have You Had Your Pill Today?”), and to push anti-establishment agendas (a skeleton in top hat satirically bursts through the original Uncle Sam image). A 1976 version created by civil rights activists depicts a black Uncle Sam, forlornly staring at the viewer; another, from the 1980s, uses Uncle Sam’s visage to promote AIDS awareness.

Elena Millie, who curated a wide variety of Uncle Sam posters for the Library of Congress, explains the figure’s timeless significance:

“Uncle Sam has that historical symbolism behind him. When you see Uncle Sam personified, you ask automatically ‘What does he want?’ He’s calling us for some sort of action. That’s why he was such a popular symbol for protest art, the underground press and guerrilla art.”

But as a personification of the United States, Uncle Sam is also a scapegoat for all of our problems. As one disgruntled taxpayer puts it, “Uncle Sam is an asshole who likes to eat money.” In one dystopian graphic novel, Uncle Sam is portrayed as a low-life vagrant wandering urine-filled streets in a fruitless search for his soul; he battles searing flashbacks of America’s worst historical moments and ultimately must confront a “dark, corrupt faux version” of himself.

Political cartoonists essentially visualize the same sentiment, and have rendered Uncle Sam as everything from Jabba the Hut to a cake-loving dimwit. He’s routinely depicted as an insensitive baron intent on stuffing every sack he can find with our hard-earned tax dollars, the buttons on his shirt clinging on for dear life.

Lasting Legacy

Several historians have since contested the origins of Uncle Sam. They point out that the name was used (long before Samuel Wilson rose to prominence) in 1775’s “Yankee Doodle” (“Old Uncle Sam come then to change / Some pancakes and some onions”), though it has never been established that this was a reference to Uncle Sam as a metaphor for America. Others speculate that Uncle Sam was a creation of Irish immigrants: in Gaelic, “United States of America” translates to Stáit Aontaithe Mheiriceá, or “SAM” (this theory is a bit farfetched).

Nonetheless, in 1961, Congress adopted a resolution that officially recognized Samuel Wilson — the once-poor meat packer from Massachusetts — as the originator of Uncle Sam:

“Resolved by the Senate and the House of Representatives that the Congress salutes Uncle Sam Wilson of Troy, New York, as the progenitor of America’s National symbol of Uncle Sam.”

Congress would also later designate Samuel Wilson’s birthday, September 13, 1989, “Uncle Sam Day” — an homage that is officially recognized today. Buried in a sea of American flags, the cattleman’s tombstone makes his legacy clear: “In Loving Memory of Uncle Sam, the name originating with Samuel Wilson.” Nearby, a statue stands in his honor — not of a media-rendered Uncle Sam, but of the unbearded, well-groomed man himself. He stands tall, dignified, with one palm turned outward and the other grasping a top hat, as if acknowledging his place in history.

This post was written by Zachary Crockett. Follow him on Twitter here, or Google Plus here.