![]()

Albert Jackson Tirrell, a 22-year-old aristocrat, sits stiffly in a Boston courtroom, awaiting a verdict on his murder trial. It’s March 24, 1846; three months earlier, Tirrell’s mistress, a prostitute, had been found dead in a boardinghouse, nearly decapitated by a three-inch deep, six-inch wide cut. By her feet, a razor blade, groom’s vest, and cane had been left soaking in a pool of blood. The bed had been set on fire. Tirrell, the last man seen with the woman, had fled the scene.

In court, prosecutors present these facts linearly, in gruesome, stark detail. Tirrell, they claim, is a lecherous, unfaithful “buffoon”: he plotted the murder to cover up his affair, so as not to besmirch his reputation. But Rufus Choate, the defendant’s renowned attorney, presents an entirely different case: his client is a chronic sleepwalker who committed the crime in “the insanity of sleep” and, as such, should not be held responsible.

Choate acknowledges that his line of defense is “peculiar,” then proceeds to pitch it with the fervor of an antebellum Billy Mays. He voraciously prances about the courtroom, first establishing, through twelve testimonies, that Tirrell has been sleepwalking since the age of six, and that his “mental derangement” has progressively gotten worse over the years: he’d accosted his brother, smashed windows, and held his cousin at knifepoint, all under a “somnambulistic trance.” Next the dean of Harvard Medical School is brought in to attest that “a man could, quite conceivably, rise in the night, dress himself, commit a murder, set a fire, and make an impromptu escape” while asleep. “Somnambulism explains…the killing without a motive,” Choate concludes, stampeding along the bench. “Premeditated murder does not.”

After two hours of deliberation, the jury emerges with a verdict: Tirrell is declared innocent. But there is a bigger implication to the case. Choate’s defense — the first of its kind — set a precedent for citing sleepwalking as a line of defense in court. In the 150 years following his trial, an array of supposed sleepwalking murder cases have surfaced, all of which have questioned the boundaries of criminal litigation.

Dazed and Confused

Via Marion Peck

Sleepwalking, also known as somnambulism, is at once a physical and psychological circumstance. Mayo Clinic defines the act as a “sleep disorder characterized by walking (or other activity) while seemingly still asleep;” Psychology Today adds that it is usually “associated with a disorder of the mind.”

A 2012 Stanford University study that surveyed 15,929 adults (aged 18 to 102) found that 3.6% of respondents reported sleepwalking at least once; pre-teen children reported much higher rates (18%). Various factors increase one’s likelihood of involuntary arousal — fatigue, anxiety, stress — but it seems to occur most frequently with those dealing with personal crises. It is also thought to be hereditary: a child’s odds of inheriting the disorder increase by 60% if both parents are affected.

A healthy, normal sleep cycle involves four stages of sleep, ranging from the onset of drowsiness (stage 1) to deep, slow-wave slumber (stages 3,4). After about 90 minutes, a person will enter a fifth “stage” — a REM (Rapid Eye Movement) cycle — during which brain activity is heightened and paralysis occurs in the major voluntary muscle groups. Generally, sleepwalking occurs during stages 3 and 4 (deep sleep), or during the transition into an REM cycle.

While most experts agree that the vast majority of cases involve minimal actions (ie. sitting up, slogging across a room, or going to the bathroom in an unconscious state), odd incidents occasionally surface. In 2012, 31-year-old Alyson Bair awoke, disoriented, deep in the waters of Idaho’s Snake River, nearly crippled by hypothermia. Deep in slumber, she had sleepwalked into a real-life nightmare. Just a few months ago, in April 2014, a 10-year-old Ohio girl rose in the middle of the night, took her father’s car keys, and drove two blocks down the road before crashing into a semi-truck and two parked cars — reportedly, all while in a transitive state of sleep. Dozens of similar cases sprout up each year.

But in the vast swath of sleepwalking incidents, a handful have purportedly resulted in the gravest outcome: murder. It seems impossible — a person unconsciously killing another person and having no knowledge of his actions the following morning — but according to legal defense teams, it isn’t just a possibility, but a reality.

Can You Sleepwalk Your Way Out of a Murder Charge?

The defense of sleepwalking is so rarely asserted that there is little precedent for defenders to go on, says lawyer Mike Horn. “There has been inconsistency among courts faced with sleepwalking defenses,” he writes in the Boston Law Review, “and so there is no objective criteria for evaluating them.” Early sleepwalking murderers, like Albert Tirrell, were consequently found innocent with little scientific or medical proof.

Several years after Tirrel’s exoneration, an eerily similar case surfaced. In 1879, a man fell asleep in a Kentucky hotel lobby; when a porter attempted to wake him, the man drew a pistol and shot the hotel worker three times. As the porter fell to the ground, the shooter writhed with glee, repeatedly shouting “Hoo-weeee!” Then he rose, walked out of the room, and confessed the incident to a stranger. A subsequent court case, Fain v. Commonwealth, found the defendant guilty of manslaughter, but the charge was reconsidered when the man claimed to have been asleep throughout the entire ordeal.

Few medical experts were consulted, save for a doctor who testified that somnambulism was a real “phenomenon,” and evidence pointing toward the shooter’s lifelong history of sleepwalking was minimal. According to case files, his defense team “introduced evidence to show he was a man of good character” and that he’d been “in a state of unconsciousness between sleep and waking” during the crime. Resting on the tenet that there can be no criminality in the absence of criminal intent, the defendant’s charge was reversed, and he was acquitted.

In 1925, Isom Bradley rose late at night in his Texas home, apparently due to a lucid dream that an intruder was present, and fired several shots; when he awoke, he found he’d shot his girlfriend. With a similar, medically-vague sleepwalking defense, Bradley was exonerated by the court, which set the following precedent:

“Somnambulist [sleepwalker] does not enjoy the free and rational exercise of his understandings and is more or less unconscious of his outward relations; none of his acts can rightfully be imputed to him as crimes.”

While these cases all focused on the defendant’s unconsciousness, insanity has also been used to prove a sleepwalker’s innocence. In 1943, a Kentucky couple’s life was dismantled when their 16-year-old daughter, Joan Kiger, had a delusional sleepwalking fit. Around midnight on August 16, Kiger had a vivid nightmare that a wild-eyed intruder was breaking into the family’s home, so she embarked on a “rescue mission.” The teen took two loaded revolvers, shot her little brother, then proceeded to her parents’ room, where she killed her father and wounded her mother. As she emerged from her somnambulistic state, she panicked and yelled, “There’s a crazy man in here who’s going to kill us all!”

Kiger was subsequently charged with first degree murder, but was acquitted — on the grounds of insanity — after using sleepwalking as a defense. Under oath, Kiger claimed to have been in a hypnosis during the ordeal, and psychological experts testified to her delusions and vivid nightmares. She was declared insane, and later spent one year in an institution.

Joan Kiger (far right), awaiting her murder verdict at Burlington Courthouse with her mother (left), and elder brother (middle); December 12, 1943

In 1981, a court verdict again categorized sleepwalking as a form of “temporary insanity.” While sleepwalking, Arizonian Steven Steinberg stabbed his wife 26 times with a kitchen knife, then told police intruders that he had committed the crime. In the courtroom, he readily owned up to the murder, but claimed that, because he was sleepwalking, he’d briefly been rendered insane. Psychologist Dr. Martin Blinder backed up Steinberg’s assessment, categorizing the murder as a “dissociative reaction.” Steinberg was found innocent, and served no time in an institution.

***

The most scientifically rigorous sleepwalking defense case in history is that of Canadian murderer Kenneth Parks. In 1987, Parks was a happily married 23-year-old with an infant daughter, and he had an especially close bond with his wife’s parents, who referred to him as their “gentle giant.” But Parks harbored a dark secret: he was a compulsive horserace gambler. He embezzled money at work to fund his habit, but was soon caught and fired. He made plans to reveal his financial ruin to his in-laws the following day — May 23 — and drifted off into an uncomfortable slumber, watching Saturday Night Live!

According to court documents, his sleepwalking episode occurred several hours into the night: Parks rose, drove 14 miles to his in-laws’ home, shattered his way through a window, strangled his father-in-law unconscious, and proceeded to stab his mother-in-law to death. He then stumbled back to his car and drove to a local police station, where he reportedly told an officer, “I think I have killed some people…my hands.”

After emerging from his supposed state of unconsciousness, Parks had a “total absence of recall.” When questioned by police, he could not recall minute actions — throwing on his jacket, putting the keys in the ignition, walking up and down stairs — or ever committing a crime. Though he’d suffered separated tendons in both hands (an incredibly painful injury), he had shown no indication of pain. In seven subsequent interviews with physicians, psychologists, policemen, and lawyers, Parks maintained a pinpoint version of what he could and could not recall. When he was charged with first-degree murder and taken to the hospital for surgery, a doctor noted that he was a “sad, remorseful, and perplexed 225-pound male.”

While in prison awaiting his trial, Parks underwent four months of scrupulous medical, psychiatric, and cerebral testing. Numerous psychologists assessed him through a variety of platforms, finding no indication of psychosis, delusions, or hallucinations:

In the Beck Depression and Hopelessness test, Parks registered within the 99th percent of both depression and hopelessness. He also underwent three Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory tests (a widely used psychometric analysis), each of which revealed his chronic feelings of inadequacy, worthlessness, and depression. A sea of neurologists conducted extensive sleep disorder tests which determined Parks was, indeed, a sleepwalker. After one test, during incarceration, two cell mates reported incidents of him sitting up during sleep, eyes open, mumbling aloud.

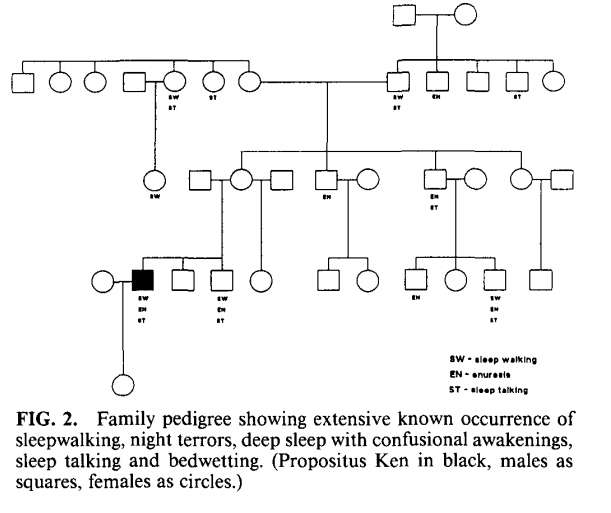

Likewise, an elaborate family tree was created, which found that Parks’ lineage had suffered from similar problems. In psychiatric evaluations, Parks revealed he had been a “severe bedwetter until age 11, a deep sleeper who was hard to awaken, a chronic sleep talker, and an occasional sleepwalker from early childhood.”

A bevy of sleep tests — EEG, EOG, EMG, EKG — showed that Parks had unusually high amounts of wakefulness and slow-wave sleep patterns — both indications of potential night terrors.

A few of Parks’ sleep histograms, which indicated insomnia and unusual REM patterns.

Ultimately, Parks’ legal team curated this knowledge and formed a defense: Parks had committed his crimes during “non-insane automatism.”

“Automatism means acting unconsciously,” Jeff Welty, a law professor at the University of North Carolina, tells us, adding that the concept began to gain traction in courtrooms in the 1980s. He continues:

“Sleepwalking qualifies as automatism from a medical-legal viewpoint, as it meets both criteria: it is unconscious and involuntary. In general, a person can’t be convicted of a crime if he or she acted involuntarily; If a jury concluded that a defendant was unconscious when he or she killed another person, the jury could acquit the defendant on the basis of automatism.”

In Parks’ case, that’s exactly what happened. The jury, swayed by the evidence presented, found him not guilty of first-degree murder, on the basis that he had no control over his actions. In his closing remarks, a Supreme Court of Canada judge elucidated his decision:

“It may be that some will regard the exoneration of an accused through a defense of [sleepwalking] as an impairment of the credibility of our justice system…however, these views are contrary to certain fundamental precepts of our criminal law: only those who act voluntarily with the requisite intent should be punished by criminal sanction.”

In the ensuing years, lawyers cited automatism as a defense in several more trials involving sleepwalking murders. Most notably, in 2003, 32-year-old Englishman Jules Lowe beat his 83-year-old father to death, reported no recollection of the crime, and was acquitted on the basis of automatism, as well as by reason of insanity. He served 10 months in a mental hospital, and was released a free man.

When Sleepwalking Fails

While the stories above are compelling, claiming unconsciousness during a murder isn’t a Get Out of Jail Free card. In several cases — usually those with strong conflicting evidence — juries haven’t bought the sleepwalking defense.

In 1994, Michael Ricksgers told police he’d woken up terrified, with a gun in his hand and a bullet in his wife’s back. His defense team presented a case built around sleepwalking and sleep disorders to no avail: Ricksgers was sentenced to life in prison without parole.

The widely-publicized 1997 case of Scott Falater ended similarly. It was a grim tale. The Motorola engineer slashed his wife 44 times with a hunting knife, shoved her into the backyard, and held her head under pool water until the water was a red sea. His neighbor, who witnessed the crime, dismantled Falater’s sleepwalking defense in court, claiming he’d exhibited signs of lucidness (ie. calling out to his dog to sit, applying Band-Aids to his hands). Police also discovered that Falater had attempted to hide the crime by stuffing bloodied garments into Tupperware containers hidden in his car. In 1999, he was sentenced to life in prison; his case later became a poster child for sleepwalking murders and was featured on a variety of forensic television specials.

Two years later, in California, Stephen Reitz, a commercial fisherman, vacationed with his lover. The romantic getaway quickly turned tragic: late at night, he “smashed her head with a flowerpot,” stabbed her repeatedly with a plastic fork, dislocated her arm, fractured multiple bones in her face, and stabbed her repeatedly with a pocket knife. He claimed to have been deep in sleep, and under the impression that she was an intruder — but a history of violence against his partners (including telling his ex he’d “gut her like a fish”) tore apart his case.

When “sleep expert” Clete Kushida was summoned by Reitz’s defense lawyer, the man’s sleepwalking claims were dismissed as egregious. “[Regarding] this whole business of committing a murder while sleepwalking,” said presiding Judge Gary Ferarri, “I think the best word is sophistry.” Reitz was declared a “monster,” found guilty of first-degree murder, and sentenced to 26 years in prison.

A Closing Statement

Ultimately, none of these cases provide formal proof of etiology (causation). That is, even when a defense team raises ample proof of a killer’s sleepwalking tendencies, it’s nearly always impossible to prove that was the root cause of the murder. At the same time, it can’t be disproven; in the criminal justice system, reasonable doubt often leads to acquittal. Limited medical knowledge of the root causes of sleepwalking has lent it to multiple associations — as an act of unconsciousness, automatism, and insanity — and has prevented us from understanding which explanation is the most accurate.

Courts’ rulings on sleepwalking as a defense have been much like one who suffers from the disorder: hazy, inconsistent, and unable to discern fact from fiction. Until it is medically decoded, legalists will continue to grasp for truth.

This post was written by Zachary Crockett. Follow him on Twitter here, or Google Plus here.