It’s your birthday party and, of course, you’re out with your family and friends at diner chain T.G.I. Friday’s. As you fork the last morsel of steak into your mouth, they descend: five waiters in pin-adorned red polos, bearing overly-enthusiastic smiles and a chocolate cake. You know what’s coming:

“I don’t know what I’ve been told! Someone here is getting old! Sound off: HAAAAPPY. Sound off: BIIIIRTHDAY. Happy birthday to you!”

‘Wait a minute,’ you think, as the quintet winds down its strange, lyrically-challenged performance. What the f*%# is this? This isn’t “Happy Birthday!” You feel juped, cheated: why couldn’t this fine establishment sing you the real deal? The answer is rather surprising: if they did, the chain could be held liable to pay Warner Music thousands of dollars in copyright fees.

Since being composed more than a century ago, “Happy Birthday (to You)” has not only become America’s go-to celebration song, but one of the most omnipresent ballads in history. The American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers (ASCAP) has called it “far and away…the most popular song of the twentieth century.” It has been played or performed billions of times by everyone from Igor Stravinsky to Marilyn Monroe. During the Apollo 9 mission, it became the first song ever officially sung in space.

Despite its accessibility, the song is copyrighted by Warner Music — a corporation that charges anywhere from $1,500 to $50,000 to use it in movies, television shows, advertisements, and musical birthday cards. But is their copyright claim really valid?

To answer this question, let’s dive into the history of the song.

Who Wrote the Music?

Most musicologists who’ve traced the origins of “Happy Birthday” agree that its musical score dates back to the work of two Kentucky sisters in the late 19th century: Mildred Jane Hill (b.1859), and Patty Smith Hill (b.1868).

After graduating as valedictorian of Louisville Collegiate Institute, Patty went on to be a central figure in the progressive education movement, endorsing hands-on learning techniques and interactive teaching methods. She invented “Patty Hill Blocks” — a set of large, cardboard bricks that children could use to learn about structural engineering — and then founded the Institute of Child Welfare Research at Columbia University Teachers College.

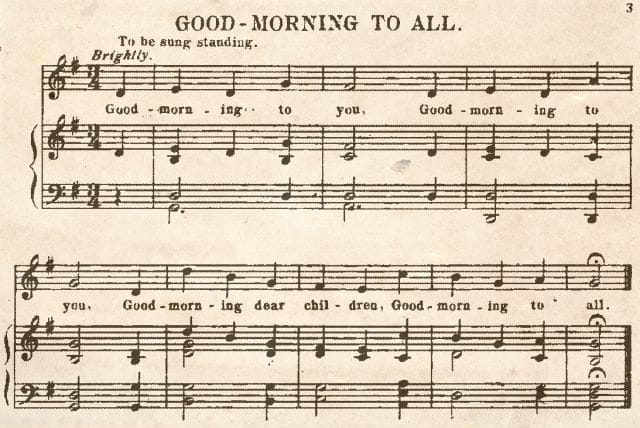

In 1889, while serving as a kindergarten teacher at a Kentucky grade school, she began working on a set of childrens’ songs with her older sister Mildred, a well-known organist, composer, and “Negro music” scholar. Four years later, the two released their first collection of tunes in a book titled “Song Stories for the Kindergarten.” Among the songs, was a little ditty entitled “Good Morning to All,” which would later be the source of the sheet music for “Happy Birthday.”

We dug up a copy of the document and have embedded it below (you can find “Good Morning to All” on page 5):

“When my sister Mildred and I began the writing of these songs, we had two motives,” Patty later stated. “One was to provide good music for children. The second was to adapt the music to the little child’s limited ability to sing music of a complicated order.”

Certainly, the song was uncomplicated. After Mildred composed and scored the music, Patty added a set of jolly lyrics, which she sung aloud to her kindergarten class every morning:

Good morning to you,

Good morning to you,

Good morning, dear children,

Good morning to all

At the time, the concept of a “birthday party” was fairly new; the birthday cake had only become popular in the 1850s, and gatherings for young children’s celebrations didn’t pick up steam until the late 1870s, when schools became age-graded. People had developed a need for a proper birthday song — and “Good Morning To All” was both simplistic and catchy enough to fit the bill.

Sometime in the early 1900s, the Hill sisters’ melody began appearing in a number of songbooks with birthday-themed lyrics — though nobody knows who re-penned these lyrics, or who was the first person to pair “Good Morning to All” with them.

An early printing of “Good Morning to You” cites it as the same tune as “Happy Birthday to You” (“The Beginners’ Book of Songs,” The Cable Company, 1912); Source: Robert Brauneis

Over the ensuing two decades, “Good Morning to You” became inexplicably linked with birthday celebrations, and eventually morphed into “Happy Birthday to You.” — and with the song’s new fame came a slew of copyright issues.

Complex Ownership

The Hill sisters’ book, Song Stories for the Kindergarten (including “Good Morning To All”), had originally been published in 1893 with a man named Clayton F. Summy, who subsequently filed copyright claims for all of its songs. At the time, the Copyright Act of 1831 dictated that a copyright was valid for 28 years, with the possibility of extending it 14 more.

For the first 20-odd years of its copyright life, “Good Morning To All” hardly made any money, but by the time Summy renewed the claim in 1921, the song’s melody had been appropriated as a birthday tune, and was in wide use.

By the early 1930s, Jessica Hill, one of Patty and Mildred’s younger sisters, began to notice that the revamped, birthday-themed “Good Morning to All” was being used across the United States without attribution. When the Broadway musical As Thousands Cheer enlisted the tune in 1933, she decided enough was enough, and filed a copyright lawsuit against its directors.

The New York Times; August 15,1934

Working with Summy, she then published “Happy Birthday (to You)” in 1935, and copyrighted “several versions of the song.” But a few years into this partnership, the Hill sisters realized Summy wasn’t paying them their share of royalties, and formed their own company, The Hill Foundation, Inc. (specifically to “administer their interests in ‘Happy Birthday to You’/’Good Morning to All’). Under this new moniker, they filed a lawsuit against Summy for back royalties.

Ultimately, the Clayton F. Summy Company was granted rights to all “Happy Birthday”/”Good Morning to All” copyrights, and in return, the Hill sisters received a one-third share of all revenues generated by the song.

Here’s where things get a bit complex.

When Clayton F. Summy passed away in 1932, his business — including these copyright claims — was bought by an accountant named John F. Sengstack. In 1957, Sengstack’s son took over, made some acquisitions, and renamed the company the Summy-Birchard Company. Around the 1970s, this company fell under a division of Birchtree, Ltd., a music education firm. Finally, in 1988, Birchtree was sold to Warner Communications Inc. for $25 million (executives at Warner later said “Happy Birthday” represented about “one-third” of this transaction).

From here, Warner merged with Time, Inc. in 1990, then Time-Warner Inc. was purchased by America Online in 2000, to form AOL Time-Warner. A decade later, Time Warner sold its music division to independent investors, who then formed Warner Music Group.

Long story short: today, the copyright to “Happy Birthday (to You)” resides under the control of Warner/Chappell Music Inc., WMG’s publishing arm.

In the midst of this, the copyright to “Happy Birthday” was extended twice — first under the Copyright Act of 1976 (which protected it for 75 years from date of publication), and subsequently under the Copyright Term Extension Act in 1998 (which added another 20 years, validating the copyright until 2030).

Over time, the copyright has proven to be incredibly lucrative for its holders. Warner/Chappell, who charges anywhere from $1,500 to $50,000 to use the song in movies, radio spots, and ads, is reported to make some $2 million a year off of the song:

As reported in Robert Brauneis’ history of “Happy Birthday,” using numbers from Jessica Hill’s will, and revenue statements

Through a series of renewals, Warner/Chappell claims to own the copyright until 2030 — and until then, the company plans to continue aggressively protecting it.

Don’t worry, you can still sing it in the shower. Warner/Chappell only sends out bills when the song is used commercially, or for public performances (defined under current copyright law as “a place open to the public, or any place where a substantial number of persons outside of a normal circle of a family and its social acquaintances is gathered”).

Validity of Copyright

There’s an interesting twist to all of this: despite raking in millions off of “Happy Birthday,” strong evidence exists that Warner/Chappell may not even own the copyright to the song.

In the opinion of law professor Robert Brauneis, who wrote a 68-page article on the song’s copyright history, the song belongs to everyone — and Warner/Chappell’s copyright claim is invalid.

Brauneis cites several “principal weaknesses” in the copyright. First, he says the copyright to the song was apparently never renewed after 1963, and is therefore part of the public domain. “The only renewals filed were for particular arrangements of the song – piano accompaniments and additional lyrics that are not in common use,” he clarifies. “It is unlikely that these renewals suffice to preserve copyright in the song.”

Second, and more importantly, a copyright holder can only claim ownership “if it can trace its title back to the author or authors of the song.” While it is clear that Patty and Mildred Hill wrote and composed “Good Morning to All,” there is no conclusive evidence pointing to the author of the “Happy Birthday” variation.

“It is almost certainly no longer under copyright,” he writes. “The melody of the song was most likely borrowed from other popular songs of the time, and the lyrics were likely improvised by a group of five and six-year-old children who never received any compensation.”

The Current State of the Song

In 2012, filmmaker Jennifer Nelson was in the midst of producing a documentary about the origins of “Happy Birthday,” when she received a notice that, in order to use the song, she’d have to pay Warner/Chappell $1,500. She paid the fee, but then got curious about the copyright’s validity.

“Before I began my filmmaking career, I never thought the song was owned by anyone,” she told The New York Times. “I thought it belonged to everyone.” After doing some research, she determined that the song was just a “public adaptation” of “Good Morning to All,” and therefore “belongs to the public, and needs to go back to the public.”

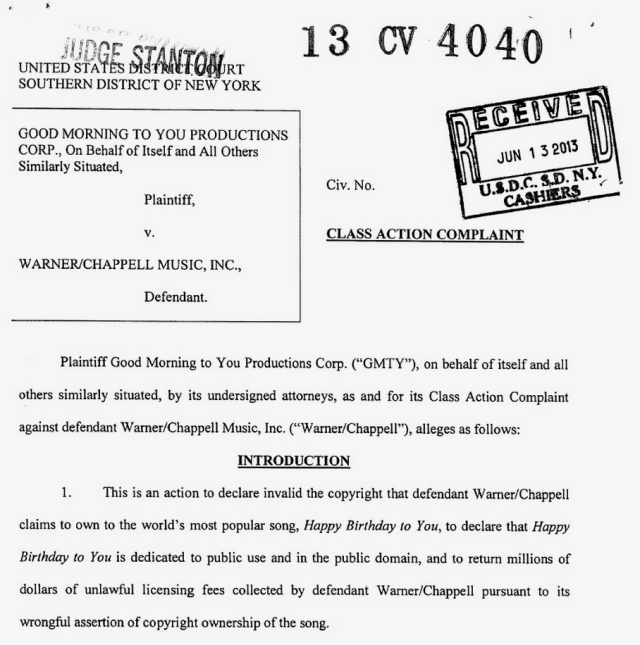

Under her aptly-named company, Good Morning to You Productions, she filed a class-action lawsuit against Warner/Chappell, demanding that they return decades of royalties to what she deems to be “unfairly charged” users.

You can click this image to read through the full lawsuit document

In the suit, Nelson and her lawyers allege that Warner/Chappell has “wrongfully and unlawfully…silenced those wishing to record or perform [the song], or has extracted millions of dollars in licensing fees from those unable to challenge its ownership claims.”

Among the suit’s citations is a book published by the Board of Sunday Schools of the Methodist Episcopal Church in 1911, which contains the modern lyrics to “Happy Birthday” alongside the “Good Morning to All” music. The religious school allegedly filed a copyright application on this combination in 1912, rendering Warner/Chappell’s copyright claim void.

Despite this apparent evidence, many experts speculate that Warner is too big to lose.

The sad truth is that challenging Warner in any capacity is neither cost effective nor promising: the goliath company has “strong financial incentive” to keep its copyright protected and out of the public domain — and, at least until 2030, it intends to do just that.

***

UPDATE (9/22/2015)

On September 22, 2015, a federal judge in California ruled Warner/Chappell Music’s copyright claim invalid!

“Because the Clayton F. Summy Company never acquired the rights to the Happy Birthday lyrics,” said U.S. District Judge George H. King, [Warner] do not own a valid copyright in the Happy Birthday lyrics.” He continued:

“[Warner] asked us to find that the Hill sisters eventually gave Summy Co. the rights in the lyrics to exploit and protect, but this assertion has no support in the record. The Hill sisters gave Summy Co. the rights to the melody, and the rights to piano arrangements based on the melody, but never any rights to the lyrics.”

Barring a change in heart at an appellate court, this ruling ends the three-year struggle of filmmaker Jennifer Nelson to strip Warner of its rights to the song. As of now, the company will no longer profit from licensing it, and it is free to use in television and the movies.

For those interested in more information, the full legal document can be read here.

This post was written by Zachary Crockett. You can follow him on Twitter here.

To get occasional notifications when we write blog posts, please sign up for our email list.