Neil Harbisson: “the world’s first cyborg.” Source: Flickr

In June of last year, Rich Lee, a Utah resident who formerly worked in finance in Hong Kong, had a pair of invisible headphones implanted in his ears.

He asked a body modification expert, who normally does piercings and tattoos, to implant two magnets under the skin of his ears. That done, Lee slipped an induction coil — the type of wire used in physics classes to demonstrate how an electrical current influences a magnet — over his head like a necklace and connected it to an amplifier. By plugging the headphone jack of the amplifier into his phone, he can listen to music privately without wearing headphones. The electrical current in the coil causes the magnets to vibrate, playing music in his ears.

The invisible headphones are not a temporary experiment. The magnets are coated in silicone so that they are (relatively) safe to keep in place, and Lee has been wearing them for over 8 months.

If you ask Lee why he did this, as we did, he’ll reply, “I realized that if I want to be a cyborg, I have to do it myself.”

Lee recognizes that this “is not a goal that everyone has now.” But he is not alone in his ambition. Lee associates with a loose-knit community of “grinders,” people interested in augmenting their human bodies with implanted technology. Other enthusiasts have implanted magnets in their fingertips so that they can feel electromagnetic fields, placed a device that sends biomedical data to the Internet via bluetooth under the skin of their forearm, and built hardware that allows them to experience color as sound.

For decades, technologists and science-fiction writers have speculated about a future in which humans meld with machines. New technologies like Google Glass, meanwhile, lead to comparisons with The Terminator and speculation that it is the first step down the path to an augmented reality.

The grinder community, however, is not waiting for the future to arrive; they’re building it by tinkering with their own bodies. And their first, do-it-yourself steps toward becoming cyborgs show that humans can already modify or augment their experience to a surprising degree.

Hacking a Sixth Sense

The most common, accessible implant grinders get is a magnet placed in a fingertip. It’s as simple a procedure as getting one’s ear pierced, yet the result is as powerful as a sixth sense.

Similar to Lee’s experience with headphones, grinders usually ask a body modification expert to implant the coated magnet under their skin. He or she makes a small incision, creates some space, and drops in the magnet. Since fingertips are rich in nerves, once the pain from the cut dissipates, grinders can feel magnetism in their fingertips.

When one woman received a magnetic implant, her companions announced, “Welcome to your new sense.” That’s not necessarily accurate. The movement of the magnet in response to electrical currents stimulates the same nerves that communicate temperature, pressure, and pain. The sense is still touch; grinders experience electrical currents as a buzzing or tingling in their fingertips.

Yet the magnet allows grinders to augment their experience of the world in a pretty radical way. Writing in Wired about her experience with a magnet implant, journalist Quinn Norton writes, “In time, bits of my laptop became familiar as tingles and buzzes. Every so often I would pass near something and get an unexpected vibration. Live phone pairs on the sides of houses sometimes startled me.” “That’s so cool!” says grinder Shawn Sarver in a documentary by The Verge as he experiences his “new sense” for the first time.

The procedure is not without risk. If the magnet breaks, it can cause infections. But many grinders enjoy their implant for years without any problem other than a gradual fade in the magnet’s power. It’s a common first implant that leaves most grinders wanting more.

Grinders work all sorts of day jobs: Rich Lee is a salesman while Sarver is a barber. Sarver previously served in the military, where he received applicable technical training. But many have no relevant background and turn to the Internet.

Everything I learned, I learned online from university lectures and good free resources. I took this Berkeley medical device course on YouTube. I learned a ton. Originally I used hot glue and pen casings. It’s insane in retrospect. I’m not an engineer — it’s new to me.

~Rich Lee

It all starts with Google searches, and grinders share their increasingly niche knowledge on online forums. Another grinder on the site biohack.me gave Lee the idea for implanted headphones.

Rich Lee’s headphones setup from his original post explaining the implant. Source: Rich Lee, H+ Magazine

As they seem to offer limited advantages over regular earbuds, we asked Lee whether his goal is to prove a possibility. But he replied that he’s “not interested in the theoretical” and “definitely wants something that will be functional now.” He considers the implant a work in progress, and he’s experimenting with different uses.

Listening to music is an obvious option, but Lee is particularly interested in attaching sensors to his headphones. He has plugged his amplifier into a metal detector and a geiger counter so that he can sense the presence of metal and radiation as he walks around. He has also used a range finder (with audio output) to hear how far away walls are.

Since Lee has a medical condition that could result in blindness, he wants to know if he could navigate by echolocation like a bat. While the range finder did not prove immediately useful, collaboration with a Harvard professor led Lee to try a device that emits sound in a 360 degree burst and captures the returning sound via microphones. There’s more he’d like to try with echolocation, but so far he already says that “it is a bit disorienting at first, but once you get used to it you find that your spacial awareness is kind of like a super power.”

Many blind people use echolocation, tapping a cane and listening for echoes, to help navigate, but other ideas would take advantage of the invisibility of Lee’s headphones. (He can hide the amplifier under a shirt and disguise the coil as a necklace, and he plans to upgrade his implant so that it’s less bulky.) Lee has considered connecting his headphones to a contact mic so that he could surreptitiously hear through walls (and considered the contact mic in a fingertip as a future implant) or passing audio from a mic through a stress analysis app to check whether a business client or poker opponent is being truthful. He even speculates that his implant could be part of a telepathy-like setup if combined with the ultrasonic speech capabilities of a larynx prosthesis, an antenna, and a subvocal microphone.

A Post Human Future

“Fuck Cheetahs, why do they get to be the fastest?”

~ Tim Cannon of Grindhouse Wetware in “Biohackers”

Many grinders self-experiment simply for the cool factor. “People either get it or they don’t,” Lee writes in an article explaining his headphones. Grinder Tim Cannon explains, “I’ve wanted to be a robot since I was a little boy, and it looks like I’m getting close.”

While living out childhood dreams inspired by the science-fiction of Isaac Asimov and Arthur C. Clarke, a number of grinders also ascribe to a philosophy that comes replete with manifestos, think tanks, and research papers: transhumanism.

Transhumanists believe that humanity should use technology to take conscious control of its evolution. They want to enhance humans’ abilities to the point that we can be said to be “post human.” The average life experience is not the end of the evolutionary line; we are “transitional humans” who can become smarter, gain more control over our environment, and live longer or even overcome death entirely.

Key to this vision is the belief that the ability to do so is coming soon, and when it does, change will come hard and fast.

Ray Kurzweil, a noted transhumanist and Google’s Director of Engineering, foresees revolutions in 3 different fields over the next several decades: a genetic revolution that allows us to “reprogram our genes” and create drugs that target disease at the molecular level; a nanotechnology revolution that allows us to “rebuild the physical world, our bodies, and our brains… atom by atom”; and a robotic revolution that produces artificial intelligence more powerful than the human brain.

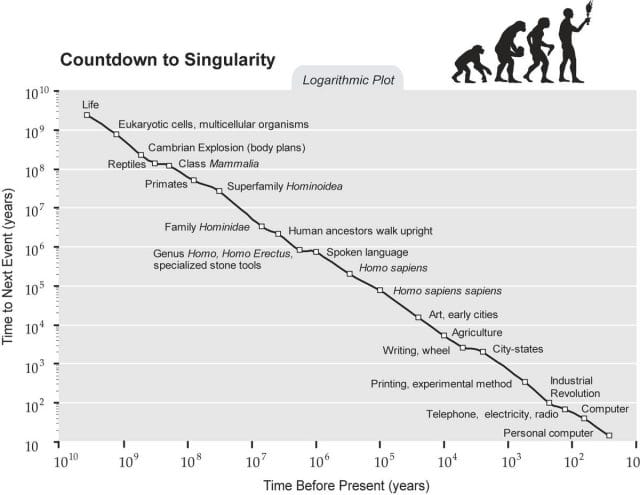

Writing in 1993, Vernor Vinge, a professor of computer science and science-fiction author, imagined intelligent machines getting increasingly intelligent and therefore progressing technology at a faster and faster clip — “in the blink of an eye, an exponential runaway beyond any hope of control.” In this way, Kurzweil expects the intersection of these 3 revolutions to result — by 2045 — in the singularity: “a future period during which the pace of technological change will be so fast and far-reaching that human existence on this planet will be irreversibly altered.”

He’s not alone in predicting such an ambitious timeframe. Vinge sets a date for the singularity between 2005 and 2030. The Machine Intelligence Research Institute, previously known as the Singularity Institute, notes that most experts predict the invention of true artificial intelligence by 2050 or 2100. The rank and file advise against taking risks so as not to miss the singularity — or recommend being cryogenically frozen.

What makes them confident in their predictions is the idea of exponential progress. Moore’s law, the name given to the observation that computer hardware gets more powerful at a predictable rate, is a common example. Like clockwork, the number of transistors on a computer chip has doubled about every two years. This is powerful because it means that while computer hardware will be 8 times as powerful after 6 years, it will be more than 4,000 times as powerful after 24 years.

Transhumanists see exponential progress at work in all technology. Whereas it took forever for humans to go from hunter-gatherers to early civilizations, we went from the Industrial Revolution to the Internet in a few centuries. According to Kurzweil, all of biological life can be described as evolution solving a series of problems to become more intelligent at an exponentially increasing rate. Once the actor was evolution, figuring out how to transfer information in the form of DNA; now the actor is sentient creatures (us) creating better and better technology until the actor is superhuman artificial intelligence.

Kurzweil’s countdown to the singularity. Source: Singluarity.com

There is more diversity of thought than presented here. But it doesn’t take long to notice the strong strand of spiritual, almost religious language. Kurzweil’s transforming of evolution’s random mutations into the inevitable march toward our posthuman future imbues an indifferent universe with meaning. Transhumanists themselves note that the philosophy can play a religious (if secular) role, and the singularity sounds a lot like heaven. Kurzweil writes:

These technological revolutions will allow us to transcend our frail bodies with all their limitations. Illness, as we know it, will be eradicated. Through the use of nanotechnology, we will be able to manufacture almost any physical product upon demand, world hunger and poverty will be solved, and pollution will vanish. Human existence will undergo a quantum leap in evolution. We will be able to live as long as we choose. The coming into being of such world is, in essence, the Singularity.

Transhumanist thought can claim some major names like Kurzweil and Vinge, and a number of think tanks have popped up, mostly in the Bay Area. But it remains on the fringe of academia and wider culture.

For some grinders, however, it’s central. Grindhouse Wetware, for example, a biohacker/grinder workspace where the aforementioned grinders Sarver and Cannon experiment, cites transhumanism as an influence. And while transhumanists don’t expect that a post human future will necessarily look like the part man, part machine cyborgs that grinders are striving toward, many see their efforts from this perspective of taking control of human evolution. Sarver says that “For me, the end game is my brain and spinal column in a jar, and a robot body out in the world doing my bidding,” but he grinds to “see if I can’t make the human evolve faster than what nature’s allowed it to be.”

The Future is Now

Rich Lee first became interested in grinders in 2008 when his grandmother passed away and he inherited a tub of her magazines from the 1950s-1970s. Out of habit, he skimmed through the science sections. They were full of artists’ renderings of moon bases (to be established by the year 2000) and futurists talking about how humans would be able to live forever. “I thought, ‘Hey! This is what I’m reading now,’” Lee told us. “It was techno-optimist b.s.”

Lee described himself as “somehow comforted by the thought that I could someday buy life-extending drugs.” He worked in international business and finance so that he could make enough money to buy a jetpack and other futuristic inventions. But he realized that everyone reading about moon bases in these magazines in the 1950s was dead now. He decided that he couldn’t wait for the future, he had to reach for it himself. He began researching online, found the grinder community, and hasn’t looked back.

Although the grinder community contains many transhumanists with whom he is friends, Lee has no patience for transhumanism. He dislikes a certain fatalism that characterizes their predictions about the future. He told us:

I think they offer too much hope to people. It’s almost proselytizing, like religion. These ideas like resurrecting the dead or uploading minds that are so far in future and no one is taking significant steps, people cling to that for hope. Nothing gets done until someone makes it happen.

Grinders like Lee are determined to make it happen, and plenty of grinders share his frustration with transhumanists tendency to prophecy. According to Lee:

The grinders arose from people like myself who got sick of waiting for transhumanists and singularity prophets to fulfill their promises. We just started hacking ourselves with the tech we have now. We collected people from the mainstream biohacking/diy bio community, body modification community, and maker communities.

They are not transhumanism’s only critics.

Many simply believe that their prediction of rapid technological progress is overblown, the 21st century version of scientists and dreamers in the 1950s who expected 2001: A Space Odyssey to be real by now. “The key point about exponential growth,” astrobiologist Paul Davies writes in a critique of Kurzweil’s book, “is that it never lasts.”

Others, less sanguine about turning over the fate of human civilization to a smarter-than-human artificial intelligence, worry about a Terminator situation in which the superhuman machines have interests that differ from our own — a worry shared by many transhumanists who debate how to prevent it at a level of intensity that is hard to take seriously when you are a human who still spends Sunday afternoons folding tube socks.

Political scientist Francis Fukuyama, meanwhile, believes transhumanism to be the most threatening idea in existence. He worries that enhancements will only be available to Earth’s richest citizens, and that “the first victim of transhumanism might be equality.” Would superhumans respect today’s consensus of equal rights and protections for all humans? Would the unenhanced become a permanent underclass, as in the movie Gattaca? In 2000, Bill Joy, the cofounder and Chief Scientist of Sun Microsystems, asked in an article whether the technologies promised by Kurzweil weren’t so rife for horrific accidents, abuse, or dystopian outcomes that humanity would not survive them.

The transhumanists, of course, have responses to these critiques and others. It’s very easy to nod along to each side. After all, what’s up for debate is an imagined future based on major assumptions. It all begins to feel very hand-wavy.

But as Lee and his fellow grinders take the first tentative steps towards integrating man and machine, they are making debates like these a bit less abstract. Grinders’ projects neither affirm nor refute Fukuyama’s worry about inequality in a post human world, but they do suggest an alternative: that it may be more of a first-mover advantage in which those not squeamish about testing the boundaries of humanity reap the benefits of enhanced abilities and intelligence.

Grinders’ experiences can also inform debates about the promise and perils of human enhancement. “I don’t believe in the techno-optimist b.s.” Lee told us. He points out that casinos wouldn’t be thrilled with his idea for a lie detection implant; his listening through walls idea could be used by cops as easily as criminals. He mentions some grinders’ (still far-fetched) ideas for a stun-gun implant. He sees grinders as interested in such ideas for “shits and giggles” rather than ill intent, but others won’t. “Black and white hats will come out of this,” he says, alluding to the terms in the computer security community for hackers who use their abilities for personal gain (black hats) versus those that inform companies of security flaws (white hats). “Any tech, you can commit crime with it.”

The Cyborg LIfe

Neil Harbisson claims to be the first cyborg recognized by a government.

Harbisson was born with a condition called achromatopsia, which is full color blindness. He filled his childhood with artistic pursuits, and when he began studying fine art at age 16, he worked only in black, white, and greys.

In 2003, he attended a cybernetics talk while in college. He proposed working with the student who gave the talk, and the end result was the eyeborg, a device that allows Harbisson to hear color. The eyeborg is a sensor that detects color (by its wavelength) and converts it into a musical note. By memorizing the sound specific to each color, Harbisson began to recognize colors and use them in his work. A later update allowed him to perceive up to 360 different shades and hues. While he once dressed only in black and white, he now dresses in a brilliant mix of colors.

The original design allowed Harbisson to listen to colors with headphones. But he decided to make the eyeborg part of his body. It is now fused to his skull, and he hears colors through bone conduction. Harbisson uses an USB cable to charge the eyeborg. He hopes to charge it using his own body energy in the future.

The eyeborg has done much more than simply compensate for Harbisson’s color blindness. His experience of color as sound leads to novel results. He judges architects like composers. He uses it in his art, as when he performs “colour concerts where I connect my eye to loudspeakers and I create sound portraits from looking at people’s faces.”He assumed that beautiful scenes like ocean scenery would sound the best, but he actually prefers grocery stores. “It’s like going to a nightclub,” he jokes. He has also used software to move beyond this artificially-induced synesthesia. Thanks to a chip installed in the eyeborg, he can see/hear light outside the visible spectrum like infrared and ultraviolet.

Harbisson decided to permanently attach the eyeborg to his body because, over time, his connection to his new sense grew until it felt part of him. He related in an interview:

“Feeling like a cyborg was a gradual process. First, I felt that the eyeborg was giving me information, afterwards I felt it was giving me perception, and after a while it gave me feelings. It was when I started to feel colour and started to dream in colour that I felt the extension was part of my organism.”

This is not uncommon. Grinders report that their implants began to feel intimately part of themselves, and it has led many to the belief that implants must always be open-source and unpatented. Plenty of science fiction imagines big companies selling new bionic parts, but to grinders it is unimaginable that a company could recall or push an update to what is essentially part of their body. It’s this identifying with the eyeborg that led Harbisson to lobby the British government to allow him to wear his eyeborg in his passport photo — he makes his claim to be the first government recognized cyborg on this basis — and seek a permanent surgery.

From Recovery to Enhancement

Grinders usually ask body modification experts to insert magnets in their fingertips or help them with their implants. That’s not because they’d like to get a tattoo or piercing at the same time. Medicine is still biased against interventions without a clear medical need — although cosmetic surgery shows that it is not absolute — which forces grinders to turn to the next best alternative (and use ice as anesthesia.)

Harbisson experienced equal difficulties in getting his eyeborg surgically attached to his skull. He spent over a year lobbying hospital administrators to allow the surgery and speaking to hospitals’ bioethics committee. In the end, appealing to its potential restorative functions convinced the hospital. He relates, “I think I convinced them when I told them that this kind of operation could help ‘fix and repair’ blind people.”

Cyborgs are normally imagined belonging to a future decades or centuries away. But Harbisson’s case shows that the barrier to becoming a cyborg is as much cultural as it is technological.

Take the example of amputee drummer Jason Barnes, a promising musician whose right arm was amputated below the elbow due to an accident. Barnes rigged up a brace that allowed him to hold a drumstick, and he performed well enough to win admission to a conservatory. While there, he met professor Gil Weinberg of the Georgia Institute of Technology, who helped build him a robotic drumming arm.

Ars Technica describes the prosthetic:

The arm uses a technique called electromyography, picking up electrical signals in Barnes’ upper arm. By tensing his right biceps in different ways, Barnes is able to control how tightly his robotic arm holds the drumsticks, and thus the manner in which the stick strikes the drum.

Using it for the first time, Barnes described it as “pretty awesome.” In many ways, it gives him a superhuman ability:

The prototype allows him to experience three-way independence between his two arms—meaning that he can perform three distinctive stick patterns simultaneously. That’s a technical capability unimaginable to most drum set players.

After using it some more, Barnes told the press, “I’ll bet a lot of metal drummers might be jealous of what I can do now.”

Medical science has produced all sorts of technology that integrates with the body. Cochlear implants that provide electronic stimulation of nerves in the ear allow people with hearing loss to perceive sound. Artificial pacemakers regulate the beating of the heart in patients with slow heartbeats. All sorts of other technologies that are in use or in development make grinders’ projects look like child’s play.

But all these technologies are aimed at restoring patients with a medical condition to “normalcy,” just as most prosthetics try to look as natural as possible. Harbisson and Barnes received their enhancements as a side effect of a defect — at least as far as modern medicine is concerned.

Perhaps the only person to benefit from the assistance of professional surgeons for his experiments with human enhancement is Kevin Warwick, a professor at the University of Reading. His unique ability to leverage the resources of a research university and a hospital allowed him to undergo a two hour surgery to have “a one hundred electrode array surgically implanted into [his] median nerve fibres” in his left arm. By connecting it to the Internet, Warwick was able to remotely manipulate a robotic hand thousands of miles away. And as his wife underwent a less invasive but similar procedure, they could communicate nervous system to nervous system, with each receiving a “pulse” in response to the other moving his or her hand.

Kevin Warwick with his remotely controlled robotic hand

Grinders find his work incredibly cool. It’s also risky, clashes with hospitals’ ethics policies, and doesn’t exactly have mainstream appeal. Companies or individuals trying to push forward on human augmentation face the obstacles of all three. Perhaps Steve Jobs or Tim Cook could have skipped the iWatch and gone straight for some sort of cyborg-like device. But it would be all but impossible to bring to market in today’s regulatory environment. In the meantime, we’re stuck with Google Glass.

For this reason, grinders are distinctly countercultural. They tend to espouse a complete lack of regard for patents and regulations that may not look kindly on their activities. When asked by The Verge why Grindhouse Wetware is located in Pittsburgh, one of its members responded that Pittsburgh has technical colleges, biomedical research, and “the right amount of fuck you.”

Cyborgs Need Rights Too

Neil Harbisson is also the co-founder of the Cyborg Foundation, which he and a colleague created “as a response to the growing amount of letters and emails that Neil Harbisson received from people around the world interested in becoming a cyborg.”

The foundation helps create cybernetic extensions like the eyeborg, which they offer freely rather than sell because they believe that the extensions, as “body parts,” should never be sold. It also defends “cyborg rights,” based off Harbisson’s experience being denied access to buildings or harassed by police for “wearing” his eyeborg. It also refuses to use the language of disabilities:

We do not intend to repair people’s senses, we make no difference between people with “disabilities” and people with no “disabilities”, we believe we are all in need to extend our senses and perception. We are all disabled when we compare our senses with other animal species.

In part, this is a common practice among those who seek not to malign the disabled as somehow “defective.” But it is also a necessary perspective for those seeking to enhance human abilities. For grinders and “biohackers,” the tyranny of normal keeps humanity from improving itself and extending its abilities. As shown by grinders’ projects, especially the magnet-fingertip implant, even simple technologies can already diversify human experience. It is our attitudes and norms that keep medicine and government regulation choking cybernetic extensions and people from clamoring for it.

“If people actively work on [human augmentation] and stop worrying about fitting in,” Rich Lee told us, “I’d like to see what creative things happen.” Many science-fiction novels (and transhumanist imaginations) foresee humanity evolving together in one direction, but Lee “wants to see hyperdiversity in the future, humans going off in 1,000 different directions, medical technology to have extra limbs or eyes…”

Grinders aren’t waiting for the future to arrive, and they don’t need to. There’s a lot that can already be done with current technology. It’s just that people may dislike the possibilities. “Often when I talk about hyperdiversity, I get resistance from people who say you can’t do that,” Lee tells us. “How will you get a job? Find a girlfriend? They worry about leaving humanity or something like that.” He laments people’s herd mentality that is too uncomfortable with differences to accept experimentation with human augmentation. As Lee puts it, “I want to scatter the flock.”

This post was written by Alex Mayyasi. Follow him on Twitter here or Google Plus. To get occasional notifications when we write blog posts, sign up for our email list. This post was revised slightly on 3/12/14 with feedback from Rich Lee.