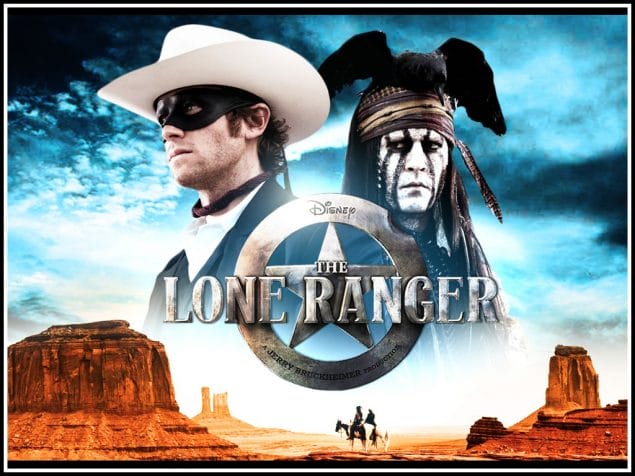

The Lone Ranger is expected to flop epically. Created at an estimated cost of $250 million, it opened to poor reviews and weak sales. Disney may take a $100 million loss.

Reviews blamed a bland script, over-reliance on action scenes, and even the makers’ hubris. But one criticism made it into every review – The Lone Ranger is too long.

This criticism stands out because it seems to be made of so many Hollywood movies, flops or not. From the Academy Award winning and highly reviewed Lord of the Rings movies to, well, the mediocre Hobbit movie, every action and drama seems to violate Alfred Hitchcock’s rule of matching the length of a film to the endurance of the human bladder.

This is puzzling because the economic incentives would seem to push Hollywood’s famously profit-first producers toward lowering costs by shortening movies. The cost of a movie ticket in theaters is the same regardless of whether it’s for a 75 minute romantic comedy or a 170 minute science fiction epic. And the same is generally true of DVDs. (An economic mystery in its own right.) It would be a risk to make movies so short that audiences feel cheated. But with audiences and movie critics clamoring for brevity, wouldn’t studios like to cut down on production costs?

During last year’s Oscar season, Daily Beast writer Ramin Setoodeh tried to figure out why movies were so long and named three culprits: the Oscars, multiplexes, and big name directors.

He quotes Rolling Stone film critic Peter Travers on how Oscar baiting leads to long movies:

“Hollywood studios believe movies are weighed by the pound when it comes to Academy thinking. If it ain’t long, it ain’t winning. Stupid, I know, since The Artist and The King’s Speech weren’t long. But ever since Gone With the Wind and Ben-Hur and Lawrence of Arabia, continuing through Titanic, Braveheart, Gladiator, and Lord of the Rings, they think Oscar will not take any epic seriously if it’s under two hours.”

He next cites someone in the business who believes that the increase in the number of multiplexes in the past decades has allowed studios to get away with longer movies. Since there are more screens, they don’t hog limited screen time as much. But you don’t need a MBA to see that theaters would still prefer to fit in more screenings every day, a complaint they have made.

Finally, Setoodeh quotes film critic David Ansen who blames studios’ deference to famous directors:

“Just look at who most of these directors are: Spielberg, Tarantino, Jackson, Bigelow. Who’s going to tell them to cut their movies?”

Oscar baiting and currying favor with successful directors seem like plausible explanations, but only if the added length does not decimate studios’ bottom lines. So how much would cutting out a chunk of a blockbuster save the studio behind it?

Not as much as we originally thought. Among the unaffected fixed costs like licensing rights to characters and distribution, the marketing costs of top films are enormous. A general rule of thumb is that the cost of advertising a movie and drumming up buzz will be 50% of the cost of producing it. So the $200+ million price tag of the Lone Ranger may not include the $100 million or so spent marketing it.

The Guardian published the following costs behind Spider-Man 2: $30 million on the deals needed to start production, $100 million on shooting the movie itself, $70 million on post-production (which includes editing and sound work but most of all the special effects), and $75 million on marketing.

For a summer blockbuster, Spider-Man 2 is not terribly long at 128 minutes (just over 2 hours). But let’s imagine what would happen if a thrifty producer had decided beforehand to decrease the length by half an hour. If we assume that the cost of shooting the film ($100 million) and editing it ($70 million) would decrease in proportion to the decrease in the lenght of the film, then the trim would reduce the cost by $39.8 million.

That’s a lot of money. It’s over 14% of the film’s cost – enough to fund the production of a film like the recent sci-fi flick Looper or pad the producers’ salaries. But in the world of blockbuster movies, where a few product placements can rope in an extra $10 million, it’s also not enormous.

We’re not Hollywood insiders, so we can’t ask executives whether they ever battle over film length as a cost cutting matter. In any event, journalists who report on Hollywood describe production costs as closely guarded secrets, constantly lied about or withheld to improve a bargaining position, spin a take on the strength of a film’s financial health, or reduce the cut given to investors and anyone else with a contract guaranteeing them a share of a film’s profits.

It seems that the potential savings from reducing the length of a movie are large enough to stoke interest but meager enough to be ceded to the lure of the Oscars and salving directors’ egos and artistic desires. We can understand why directors would choose to make long films from our own reluctance to cut down on our own articles that go on for thousands of words. And although succinct stories are often better than bloated ones, the perception of a bias in favor of long movies at the Oscars strikes us as sound – similar to the bias people hold by thinking that heavier products are of better quality.

It doesn’t look like movies will be getting shorter anytime soon. A 1984 article in Time Magazine asked “Why do movies feel so long?” It complained about the length of movies like Scarface and The Right Stuff just as we complain about the length of Lincoln and The Hobbit today. Perhaps one of our entrepreneurial readers can invent a solution to the “running for the bathroom halfway through The Dark Knight” problem.

This post was written by Alex Mayyasi. Follow him on Twitter here or Google Plus. To get occasional notifications when we write blog posts, sign up for our email list.