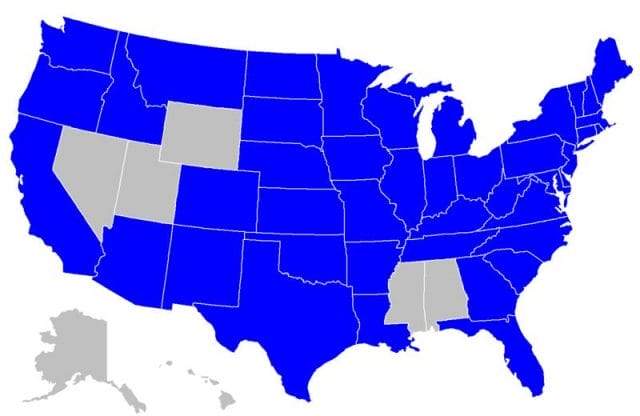

States that run lotteries in blue. Source: Wikipedia

They are available in convenience stores and gas stations around the country: lottery tickets, scratchers… the chance to win a fortune. Or, more often, $3. Like any form of gambling, buying lottery tickets essentially amounts to throwing money away: The expected value of buying a $1 ticket is around 50 cents. But even if you know the odds, there is something to enjoy. The fantasy of getting rich, the anticipation, the ritual of playing, and the burst of dopamine from even a small win.

The ubiquity of lottery tickets is odd. Unlike slot machines or roulette tables, they are not the preserve of Las Vegas. In fact, Vegas is one of the few places where they can’t be found. Nevada is one of 6 states that don’t allow lotteries. Even stranger, the states that allow lotteries maintain a monopoly on the practice. Why are the same governments banning and regulating casinos responsible for running a form of gambling worth nearly $80 billion in annual sales in the United States alone?

A little history can help us understand how states ended up embracing one form of gambling even as it disdained of others.

Lotteries can claim a proud American heritage. The company funding the settlement of Jamestown held a lottery — with permission from the British Crown — to finance the venture. Lotteries sponsored by all 13 colonies and popular Americans like George Washington financed public works including the construction of Harvard and Yale, churches, and libraries. (The practice of paying for infrastructure with lotteries has a long history that may date back to the construction of the Great Wall of China.)

Opposition to Britain’s rules about the holding of lotteries fueled anger alongside the taxation without representation mantra, and the Continental Congress tried to finance the revolution with a lottery, although it failed to sell tickets. And early America’s opposition to taxes made lotteries a popular option for financing government projects in the the young republic.

Lotteries were not without controversy — a number failed due to either logistical problems, fraud, or moral opposition by those expected to buy tickets. Nevertheless, lotteries remained a staple fundraising tactic into the 1800s. Religious opposition, fraud, and the social reform movements that took on issues like temperance and educational reform eventually brought gambling and lotteries to heel (social reformers believed the lotteries targeted the poor). In 1878, Louisiana ran the only legal lottery in the United States. In the 1890s, national legislation prevented lotteries that crossed state borders and 35 states constitutionally banned lotteries.

Legal lotteries took place only intermittently (although illegal ones still enjoyed popularity) until the Great Depression and World War II, when the need for cash and stimulus overcame the reduced opposition to gambling and lotteries. In 1964, a referendum by New Hampshire voters legalized a lottery to close a state budget gap and fund the school system. A majority of states eventually followed New Hampshire’s example.

It’s a testament to the endurance of the opposition to gambling that no privately run lotteries exist. (Although some run lotteries on behalf of state governments.) Given the easy money available, it’s a miracle lobbying and/or fraud never managed to legalize the practice for private interests.

Politicians, voters, and other actors have legitimized lotteries by linking them to activities of apple-pie wholesomeness: funding education budgets, building libraries… one law during the Depression selectively allowed bingo at churches as donations dried up.

But there’s no getting around the dark aspects of lotteries. For starters, even if lottery profits go toward a specific good like the education budget, permanent lotteries don’t really support any one aspect of a state’s budget. Funding is fungible, so lottery earnings paying teacher salaries frees up other tax revenue to pay for police pensions, infrastructure, or anything at all.

As alluded to above, one could say that lotteries target the poor, or at least that poverty traps enable them. The poorest and least educated 20% of Americans purchase the “vast majority” of lottery tickets, and one study found that households with incomes less than $12,400 spend an average of 5% of their annual incomes on lotto tickets. “Give your dreams a chance!” the New Jersey lottery admonishes residents.

For this reason, some critics call lotteries a regressive (as opposed to progressive) tax. While the word tax may seem disingenuous for a voluntary act, it’s perplexing that the same governments trying to protect poor and uneducated consumers from predatory payday loans and credit card fees run programs whose revenues depend on poor decision making (or ignorance of the odds) by those of little means. Is the extra revenue worth the social cost?

One of the few defenses of the government’s monopoly is that lotteries constitute a “natural monopoly.” Since a few large jackpots hold much more interest for people than many small ones, the logic goes, the industry is most efficiently run in a limited fashion by just one actor. Powerball, for example, has a minimum advertised jackpot of $40 million as of 2012.

We’re not sure that passes the sniff test. Vegas shows no shortage of interest in games of chance of all payoff levels, and lotteries in the United States have weathered the large increase in the number of state-run lotteries by designing games that heighten buyers’ involvement and anticipation.

A history of mixed prohibition and support helps explain why governments hold a monopoly over the running of lotteries. But in the end, the right explanation seems to be the simplest one, and the same reason everyone plays the lottery: States need the money and are lured by the prospect of an easy way to get it. Only for the states, unlike for all but a few of their poor residents, it actually works.

This post was written by Alex Mayyasi. Follow him on Twitter here or Google Plus. To get occasional notifications when we write blog posts, sign up for our email list.