![]()

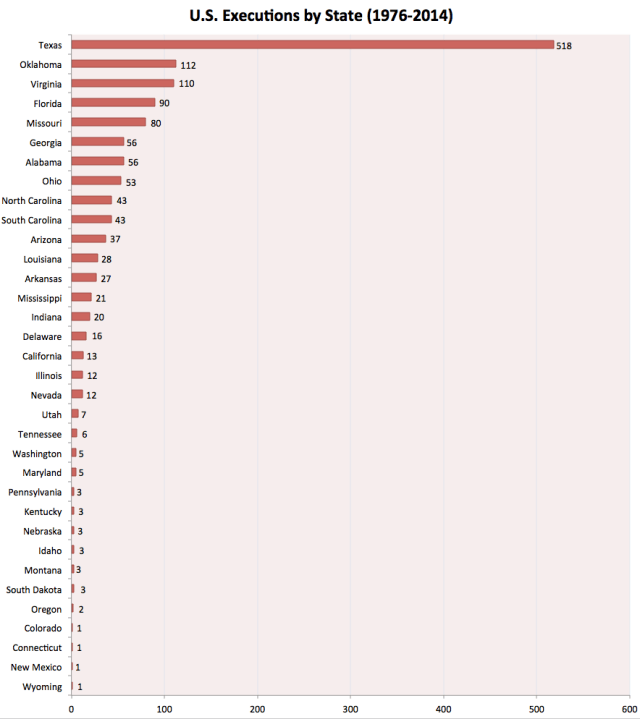

Following the Supreme Court case of Furman v. Georgia in 1972, capital punishment was qualified as “cruel and unusual,” and was suspended as unconstitutional in the United States. Since this moratorium ended in 1976, 1,398 death row inmates have been executed — 518 of which, a whopping 37% of all U.S. executions — have occurred in Texas.

Texas is, in the words of one New York Times reporter, “the gold standard” for execution proficiency. “The state,” writes PBS Frontline, “has become, [over the last 30 years], the ground zero for capital punishment.” This distinction is no secret: Texas’s kill stats are rattled off by media members, politicians, and crime agencies with practiced precision every time an inmate is put to death.

But one question is rarely addressed: why Texas?

Priceonomics; Data via DPIC

In the last 38 years, Texas has killed nearly five times the number of inmates as the next state on the list, Oklahoma. The state’s 518 executions trump Florida (90 executions), California (13 executions), and New York (0 executions), all states with comparable populations, by a landslide. From 2001 to 2014 alone, Texas Governor Rick Perry oversaw 279 executions, more than any other politician in U.S. history.

It wasn’t always this way. The Espy files, a database that collects historical data on executions, yields that between 1834 and 1972 (a 138-year period), 755 prisoners were put to death in Texas — a rate of 5.5 per year.

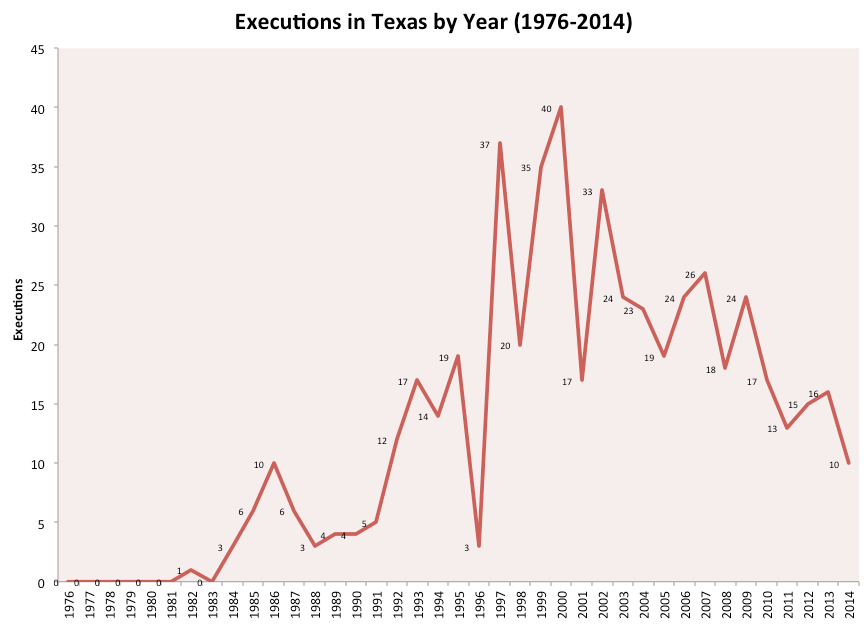

In the last 38 years (1976-present), 518 have prisoners been executed — a rate of nearly 14 per year. A look back at Texas’s execution history during this period yields a massive spike in the late 1990s, following by a gradual decline since:

Priceonomics; Data via DPIC

So, what happened?

In his paper, “Capital Punishment: Texas Could Learn a Lot from Florida” (1998), Houston law professor Brent Newton surmised that his state’s high numbers could be attributed to three factors at the time: the way judges were elected, a weak public defender system, and a flawed jury system that didn’t allow for the consideration of mitigating evidence.

Texas’s appellate judges, says Newton, were (and still are) “elected to office and hence serve according to the pleasure of the public.” To win re-election in their conservative state, these judges must maintain a strict stance on capital punishment. The result of these politically-driven desires is often a lack of careful review of cases, and a disregard for the “complexities” of each case. Newton elaborates:

“Especially during the past few years…the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals has refused to publish most of its decisions in death penalty cases, including many cases that discuss important issues of first impression. Often these opinions take positions entirely inconsistent with prior decisions by the court and fail to mention the conflict. Generally speaking, there is a hit-and-mostly-miss quality in the Court of Criminal Appeals’ death penalty decisions. Only a few judges during the past decade have been capable of or willing to write thoughtful, scholarly decisions, whether granting or denying relief.”

Really, the issue boils down to appeasing voters, and data shows that Texans are among the nation’s most ardent death penalty supporters: 73% of Lone Star State residents are in favor, as gauged with 56% in California, 45% in Florida, and 63% nationally.

A breakdown of Texas’s executions by county proves Newton’s point on a smaller scale. As the National Journal writes, “while states are generally responsible for administering executions, the sentences begin at the county level” — and these counties’ district attorneys, who are also elected, are often pressured to come down hard in death penalty cases. In Texas, just four counties (of 254 total) account for more than 50% of the state’s executions:

Admittedly, these four counties are among those that are the most populated — but these high execution rates can also be attributed to the counties’ lawmen. Harris County, which ranks first in Texas with 122 executions since 1976, was, for twenty-one years, under the jurisdiction of District Attorney Johnny Holmes — a “gentleman rancher” notorious for his no-holds-barred stance on executing death row inmates.

“His philosophy was to seek the death penalty often, and he ran on that platform,” Richard Dieter, executive director of the Death Penalty Information Center, told the National Journal. “Since Johnny left, the number of death sentences [in Harris County] has dropped dramatically.”

Secondly, Newton cites Texas’s ill-equipped public defender system. Often, he writes, “indigent defendants” are given court-appointed lawyers who have very little experience with capital murder defenses. Bad lawyering is especially abound in Texas, as recalled by PBS:

“One decision, which turned down a defendant’s habeas appeal due to bad lawyering, concluded that ‘[t]he Constitution does not say that the lawyer has to be awake’ during trial proceedings.” Until September 1995, the state wasn’t even required to offer free legal services to post-conviction defendants.”

“I think you’d find our state government and county government are more parsimonious with the money needed to provide defense counsel for indigent prisoners,” Texas’s former Attorney General told Christian Science Monitor in 1998. “Our death-row inmates overall have a very difficult time getting adequate representation on their cases, particularly after the first set of appeals.”

Lastly, Texas is also infamously prude when it comes to allowing jurors to consider mitigating evidence, like mental illnesses, or youth, when considering capital charges.

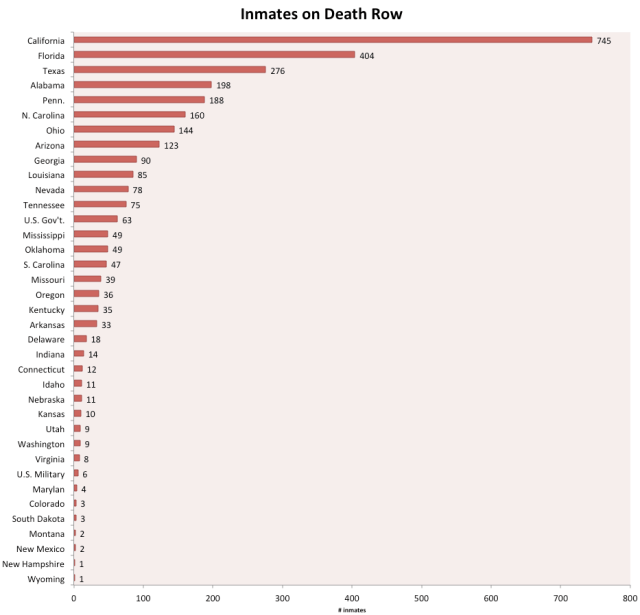

Though Texas executes the most prisoners in the U.S., the state is does not top the list in the number of inmates on death row: that distinction goes to California — a state which has only executed 13 inmates since 1976, yet holds 745 in limbo:

Priceonomics; Data via DPIC

California hasn’t executed a death row inmate since January 2006; Texas, on the other hand, has averaged around 15 executions per year over the last decade.

In addition to the factors listed above, Texas’s execution rates can be attributed to its federal appellate structure: its federal appeals are made to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit — a court that legal scholar Michael Sharlot cites as “highly conservative,” and offers fewer “legal obstacles” with death penalty cases than the Ninth Circuit, to which California makes its appeals.

Though Texas’s rate of execution has declined considerably since peaking in 2000, it continues to be aggressive: the state has 12 executions scheduled for 2015, starting next week.

So, in Texas, where nearly one-third of the United States’ executions have occurred, a number of factors are at play: a more conservative appeals circuit, the political desires of district attorneys and judges, and a defense system that is lacking when gauged against those of other states.

But some contend that there’s a simpler answer: Texas has “worked out the statutory and procedural ‘kinks’ in death penalty cases and appeals” — that is, through practice, the state has perfected the art of killing inmates.

“Texas executes so many people because it executes so many people,” writes David R. Dow, a professor at the University of Houston Law Center, in Politico Magazine. “[K]illing people is like most anything else; the more you do it, the better you get. If killing people were like playing the violin, Texas would have been selling out Carnegie Hall years ago.”

![]()

This post was written by Zachary Crockett. You can follow him on Twitter here.

To get occasional notifications when we write blog posts, please sign up for our email list.