If you go to the movies with a group of friends, people will almost inevitably debate whether the movie was good. This can be fun, but it’s never constructive. Battle lines harden as the haters argue with those who were entertained. To understand why these arguments are bound to fail, it’s helpful to think about the professionals who do it for a living.

Reviewing movies for a major newspaper is a strange job. The critics often have a background in English or film studies and spent time in college dissecting metaphors, plot structures, or cinematography. Once ensconced at a paper like the Boston Globe or the L.A. Times, however, they spend their time writing pithy reviews that are half plot summary and have all the subtlety of a thumbs up or thumbs down verdict. As Ty Burr of the Boston Globe once described the job, critics answer the question: “Is this movie worth… dropping 40 bucks on popcorn?”

Critics also write longer reflective pieces on movies’ themes and place within pop culture. (Perhaps a rumination on why new superhero and Bond films are grittier than their predecessors.) But when it comes to the three out of four stars reviews that pepper newspapers every week, why bother? What do they offer over a friend who saw the film? Or the audience score on Rotten Tomatoes? Since the tastes of experts and devotees often differ from the average consumer, wouldn’t almost anyone do just as good if not better a job?

Yet we argue with friends about movies because our preferences differ — even on the most formulaic popcorn flicks. Unless you are the perfectly average American consumer, aggregate scores may not be relevant to you. And if you ask a friend whether it’s worth seeing a movie, they won’t be able to explain why they liked or disliked the movie to help you figure out if their opinion is relevant to you.

Consider the findings from psychology — popularized by Malcolm Gladwell in Blink — about the power of snap judgments. A number of experiments have shown that people are remarkably good at evaluating anything from teaching ability to election results based only on clips as short as several seconds of the professors or politicians in action. It seems that in the few seconds we spend grasping for small talk when we meet someone new, our “adaptive unconscious” analyzes a large number of subtle cues to make judgments about the other person. And the power of our snap judgments extends beyond opinions of other individuals. In Blink, Gladwell looks at examples that include fine art, music, and armchairs.

These snap judgments are not perfect; they are susceptible to biases like racial prejudice and overconfidence. But in general, our snap judgments are remarkably prescient, which is remarkable since we don’t understand the logic behind them. People who accurately judge a teacher’s ability with students from a 10 second clip can’t substantiate their judgment. In one experiment, the correlation between what speed daters said they were looking for in a partner and the characteristics of the people who they actually expressed interest in was essentially insignificant. When we meet someone we like, we don’t really know why. We simply grasp for justifications.

And this is why arguing about movies never leads anywhere. Our intuitions usually rule our long-term opinions. Focusing on the pitfalls of these snap judgments, nobel prize winning psychologist Daniel Kahneman’s latest book describes the difficulty of overcoming snap judgments. We can even imagine a Malcolm Gladwell movie critic system in which people watch a few short clips from a movie and then rate it based on their gut reaction. (We imagine that trailers can fail to elicit our eventual opinions of movies because they essentially have a different director and style that uses the film as raw material to build a mini-movie.)

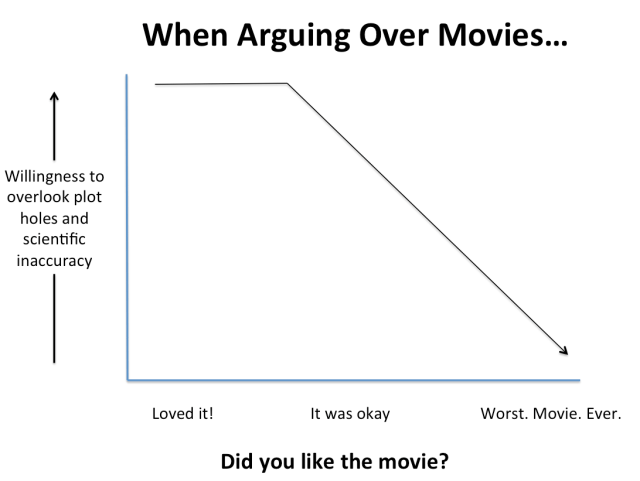

This is why those debates with friends are useless. One person likes the movie; the other doesn’t. For both, their opinion is likely a reaction that, like with the speed daters or the subjects in the experiments watching 10 second video clips, they don’t fully understand and definitely can’t articulate. The result, as expressed in the above chart, is that both sides make arguments based on irrelevant justifications. Conversations like this are the result:

Author: The special effects were cool, but the story was terrible. I hated Avatar.

Author’s girlfriend: I liked Avatar. The story was lame, but I liked the visuals.

If you like a movie, you excuse its faults. If you hate a movie, you cite those faults as the reason why it’s a terrible movie. So in the case of the recent X-Men movie:

Author: It was entertaining. But the time travel was stupid.

Author’s girlfriend: Well if you want to be scientifically accurate, most mutations cause cancer.

The idea of using humans as batteries is stupid. But you look past it if you like The Matrix. The “it’s all in the main characters head” premise is terrible filmmaking when you dislike a movie, but it’s completely forgivable when you enjoy the movie. Ditto for plot holes, time travel paradoxes, and unrealistic fight scenes. It’s probably not news to anyone that arguing over movies never changes either sides mind. But people should probably know that it’s doomed from the start.

This post was written by Alex Mayyasi. Follow him on Twitter here or Google Plus. To get occasional notifications when we write blog posts, sign up for our email list.