When the first M&M’s rolled off Mars’ production line in 1941, they originally came in five colors: brown, yellow, green, violet, and red. And by the late 1960s, the red M&M had established himself as the brand’s unheralded spokesman: early commercials and advertisements featured the carmine character dancing alongside his yellow-coated peanut friend with unadulterated joy. He was riding high, recognized by millions of adoring fans.

Then, in 1976, the red M&M disappeared.

For a decade, the color was nowhere to been seen in the candy’s packets, relegated to non-existence by incredibly flawed Food and Drug Administration research. The death and rebirth of the red M&M tells a tale of both governmental incompetence and the collective power of consumers.

The Red Scare

Following its synthesis in 1878, Red Dye No.2, also known as amaranth, became the 20th century’s most widely used food coloring; by 1970 it was being used in $10 billion worth of products — soft drinks, candy, hot dogs, ice cream, and processed fruits.

Under 1938’s Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act, Red No.2 underwent a series of tests that were inconclusive of any harmful effects. In the 1950s, several children became gravely ill after eating Halloween candy containing Red No.2, but the dye was subsequently exonerated of any blame. The FDA continued testing through the 1960s, concluding each time that Red No.2 “had no significant influence on the formulation of tumors” in lab animals. It was, by all accounts, safe and acceptable.

Then, in 1970, a group of Russian scientists ignited a red-tinted shitstorm. The Moscow Institute of Nutrition study fed male rats controlled doses of amarath over a period of 33 months, and found that 13 of 50 (26%) developed tumors. The following year, a second Russian study done with female rats resulted in a high percentage of stillbirths and deformities. Though American scientists immediately rejected the Russian study’s methodology, the FDA took serious action and ordered further investigation. Over the next four years, a series of equally flawed American tests ensued.

Finally, in 1975, the FDA commissioned a “definitive” study to determine whether or not Red No.2 had carcinogenic effects. What ensued was what one scientist called “the lousiest experiment” he had ever seen in his life:”

“The scientist originally in charge of the experiment left the agency midway through; handlers mixed up the rats, blurring the distinction between those given dye and those not; and most of the rats that died during the experiment were left to rot in their cages.”

By all accounts, the evidence was inconclusive — if not an incoherent mess. At first, the FDA declared that Red No.2 had “no apparent adverse effects on rats,” but this was immediately contradicted by the unsubstantiated claim of a statistician at another government agency. The FDA’s commissioner, Alexander Schmidt, wasn’t used to all the media attention he was getting and became flustered. Despite admitting that there was “no evidence of a public health hazard,” Schmidt folded under pressure in 1976, revoking the dye’s provisional approval, removing it from the FDA’s Generally Regarded As Safe (GRAS) list, and banning its use.

Much of the impetus used to ban Red No.2 was speculated to be based on its status as an “unnecessary product,” rather than any definitive proof that it was harmful. In the wake of the scare, the Consumers Union specified that it was “neither a valuable drug nor an indispensable food staple.” Scientists argued, no to avail, that a human would have to consume 7,500 cans of soda a day to equal the lab rats’ level of consumption — Schmidt and the FDA were steadfast in their decision.

Red Bids Adieu

In the aftermath of Red No.2’s ban, the media went on a frenzy, denouncing the dye as a carcinogenic, tumor-inducing agent. Americans, already on edge from a Swine Flu scare a few months earlier, panicked. A hysteria ensued that saw hundreds of brands recalling their Red No.2-infused products: hot dogs were pulled from grocery aisles, dog food was discarded in droves, ice cream treats were left to melt in landfills — and the red M&M disappeared.

But the red M&M never even contained Red No.2 — Mars had always used the less controversial Red No.40 — so why was the candy discontinued?

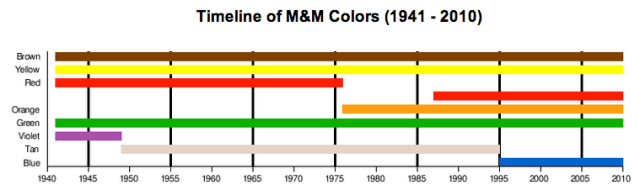

According to M&M’s public relations department, “the red candies were pulled from the color mix…to avoid customer confusion.” Instead of explaining that the red M&M didn’t contain the denigrated dye, the company ceded to the public’s anxiety of anything red, and replaced the color with orange (see timeline above).

For nine long years, the red M&M lay in respite. Shunned to the dark corners of obscurity by his orange nemesis, he vanished entirely from packaging, print advertisements, and television spots. In an early 1980s commercial, he’s nowhere to be seen:

It wouldn’t be until 1985, under the heroic efforts of a college student in Tennessee, that the red M&M would make his hallowed return.

Society for the Restoration and Preservation of Red M&M’s

Paul Hethmon was in eighth grade when the red M&M was discontinued. At the time, he recalls, there were isolated protests over the candy’s ceased production, but they “ran their course.” For some years, he resentfully wallowed in the defeat of his favorite M&M color, which he once “saved until last to savor.”

But by his freshman year at the University of Tennessee, the photo editor could no longer bear the pain of separation. In 1985, Hethmon founded the Society for the Restoration and Preservation of Red M&M’s and wrote a series of appeals to the Mars Company, Ronald Reagan, and the FDA. “Thanks for your note,” Mars wrote back. “However, we have no current plans to reinstate the red M&M.”

Meanwhile, Hethmon’s efforts started a revolution: thousands of letters poured in from around the world, including this gem from a St. Louis woman:

“Is my life worth living without red M&M’s? This is the question I had often asked myself. For many years now, I have somehow managed to go on, thinking there was nothing I could do. One person against the world! But now I have a purpose, a meaning in my life. My life is meant to give re-life to the red M&M’s.”

Hethmon’s campaign invoked a mass sentimental recollection of how things used to be. “M&M’s without red,” wrote another supporter, “are like the Three Stooges without Curly.” Even those who’d never seen red M&M’s joined the cause: a class of third graders vehemently demanded that the color make a re-entry. The media — who’d championed the red M&M’s demise ten years earlier — jumped in on the bonanza and became the candy’s biggest champion.

When asked what his motivations were — after all, all M&M’s taste the same, regardless of color — Hethmon responded with conviction:

“How can I explain this? It was like the difference between seeing ‘The Wizard of Oz’ in Technicolor and in black-and- white. You just don’t want to picture the Yellow Brick Road in black-and-white. That`s what M&Ms were like without the red ones.”

In a matter of weeks, his demands were met.

“Good things happen to those who wait,” the Mars company wrote in a note to Hethmon, “and all the associates at M&M/Mars wanted me to be sure that you were the first to receive the news.” With the letter, Hethmon received a coupon for a pack of M&Ms.

The company, riding on a wave of unsolicited PR, reintroduced the red M&M to great fanfare during Christmas of 1985; the “red scare” had long since subsided and the public embraced the treats with open mouths. Not to spark another wave of discontent, Mars kept the orange color in the lineup, and set new proportions for each bag of plain M&M’s: 30% brown, 20% red, 20% yellow and 10% each of orange, green and tan.

A 1987 commercial showcases the red M&M, who, reinstated, can hardly contain his joy:

Since being ousted, the red M&M has returned with a vengeance. In 1995 he was “rebranded,” as the candy’s poster-child and starred in a series of commercials voiced by Jon Lovitz (and later, Billy West of Futurama fame). For today’s candy connoisseurs, the red M&M is ubiquitous: he’s cocky, confident, and can’t seem to get enough of the spotlight.

But no amount of retribution could possibly repair the red M&M’s damaged psyche: for years, he was unfairly excluded, a victim of unsubstantiated FDA tests and media uproar. It’s come with a consequence.

“Red has trouble showing his emotional side,” says Jason Lucas, senior creative director for the advertising agency that represents M&M’s. “The only way he can say ‘I love you’ is with the candies.”

This post was written by Zachary Crockett. Follow him on Twitter here, or Google Plus here.