Julie Fiveash reviewing comics for Comix Experience

“Sometimes I worry,” Julie Fiveash says, as she folds newsletters behind the register at a comic book store in San Francisco. “I went to an Ivy and studied art, and now I just make stupid comics.”

“Mostly I don’t care,” she explains. “But lately I’ve been thinking, ‘Man, should I be making more serious comics? Should I be making comics about more serious things?’ Like, I think issues of representation are super important, for example.” (Fiveash is of Native American descent.)

Fiveash’s dream is to make comics for a living. These days, the best way to break into comics is by putting your stuff online and building a fan base. The trouble is that this usually takes a very long time to pay off. To support yourself through it you usually need a day job. Fiveash says she’s lucky: her day job is giving her top-notch comics education. Since September, the 24-year-old Dartmouth grad has been working as a clerk at a store called Comix Experience. When she came on she was making making minimum wage. Now she makes a little bit more.

“I’m OK with that,” she insists. “I’m willing to stick it out and do this for as long as I can. I just really, really want to work at a comic book store. I’ve always wanted to.”

It turns out that despite the low pay and lack of glamour (at least among outsiders), clerking a comic book store is a surprisingly common step on the path to being a professional comics artist. Serious artists, including Matt Fraction, Amanda Connor, and Cullen Bunn, all worked in comic book stores at some point in their careers. And according to Fiveash, they’re just the tip of the iceberg.

“There are artists who haven’t,” Fiveash says. “But it’s common enough that unless I find out otherwise, I kind of assume they have.”

This works is because in 2015 both the culture are the economy of comic book retail are surprisingly robust. Comic book stores might seem kitschy and niche, but they’re not going away anytime soon.

Indie Comics School

A single-panel strip by Fiveash, drawn before getting her job at Comix Experience. Fiveash is awesome.

In the 1980s and the 1990s the neighborhood video store was known as the “film school of the independent film world.” Directors like Kevin Smith (Clerks, Dogma, Chasing Amy) and Quentin Tarantino (Pulp Fiction, Kill Bill, Inglourious Basterds) got their start clerking. The jobs let them watch endless movies for free, in the downtime between duties, and incentivized them to hone their critical expertise. Because a good clerk was someone who could provide a good recommendation to a customer with even the most obscure taste, clerks were hired based on their passion for and knowledge of film.

“This knowledge was honed and kept visible in countless local rituals and arguments,” as Joshua Greenberg writes in From Betamax to Blockbuster: Video Stores and the Invention of Movies on Video. “Video clerks argued playfully: whether a given film was noir or not noir, which was the best Star Wars movie, countless bull sessions about genres, characters, directors, and writers.”

This sounds a lot like what Julie Fiveash does. She was hired partly for her ability to talk shop. For starters, like any good comic fan she knows the difference between a graphic novel and a trade paperback. Her job interview questions included: “What’s the edgiest thing that comics are going towards?” (QR codes in Bee and Puppycat), or “What are the monthly things you’re reading?” (Saga, duh), or “I’m looking for a comic about Jack the Ripper?” (From Hell by Alan Moore).

That pays off. Walk in, say you like artist X and book Y and you’re looking for a gift for your 10-year-old niece: Fiveash has got you covered. She’s a darn good recommendation engine. The author asks for kids’ book recommendations like the work of Chris Ware or Seth. “My thought process is like: definitely a kid’s book, but artier, takes some sort of thinking,” she explains, and knows exactly where they are in the store. “Try Hildafolk! Or anything by Shaun Tan.”

Cropped cover of Hildafolk by Luke Pearson

She has extended critical debates about comics and comics news with patrons and co-workers, many of whom are artists themselves. She gets to meet the more famous writers and illustrators who come through the store for events, and she gets to watch and psychologize customers.

“I’ve learned a lot about what people look for in comics,” she says, “and what makes a comic book sell.”

Then, of course, there’s the most obvious perk. If she counts the weekly and monthly serials, she estimates she’s been reading about 17 free comic books a week, in the downtime in the shop. “I freaking love my job,” Fiveash says, “When there’s nothing to do I’m just reading comic books constantly.”

It should be pretty clear why Fiveash thinks her job is awesome. The next obvious question is why that job still exists.

These days, more and more people stream their video entertainment online. The impact is cultural as well as economic — not only do most of the surviving stores do slow business, but filmmakers mostly don’t think about them, except as an artifact of a bygone era. Video stores aren’t indie film schools any more, because there aren’t many video stores and there aren’t many video store customers. And knowledgable, talented, passionate people aren’t drawn to them.

For decades, people have been predicting a similar end for comic book stores. Digital comics — cheap and convenient — were supposed to kill them, but they haven’t. 2014 was the best year ever for comic book sales, 2013 was the second best year. And though in many other industries — like regular book retail — online retailers are making a hefty dent on traditional shops, comic book stores are comparatively thriving. As the San Francisco Chronicle put it in January 2015:

While the struggles and closures of brick-and-mortar bookstores have made headlines in recent years, comic book stores have been the retail version of Wolverine from the X-Men — displaying an uncanny ability to adapt and survive.

“Everything is supposed to have conspired against comics to put us out of business,” Joe Field, the owner of a comic book store in Concord, said in an interview in the Chronicle last year. “But I mean this in the nicest, positive way: I believe that we’re probably the cockroaches of popular culture.”

The Cockroaches of Popular Culture

Panel from Peter Kuper’s comic book adaptation of Franz Kafka’s Metamorphosis

Brian Hibbs is Fiveash’s boss: the bearded, long-haired owner and founder of Comix Experience. He has authored multiple books on comics retail, and has kept a weekly column on the subject for decades. It’s his job to know this industry, and Hibbs has plenty of theories about its adaptability and longevity, but they all depend on fanaticism and love.

Before video stores, before video, before TV even, there were comics. Those comics were originally sold in tiny news stand racks at mom and pop groceries and pharmacies. Hibbs says that as those independent retailers were bought up by chain drugs stores, the new owners realized, “Wait a minute, instead of comics we could put in a rack of sunglasses and make a lot more money!”

Comics fans weren’t about to let comics die, and through their ingenuity the modern comics shop was born. Until the 1970s, comic book retail worked more or less the same way as regular book or newsstand retail: store-owners bought books at a discount from distributors, and were allowed to return a certain percentage of the books that did not sell for a refund. Phil Seuling approached Marvel and DC in 1972 and asked if he could buy comic books at a much higher discount, but forego some or all of his returnability rights.

This system — called the direct market — made comic selling profitable again, and let smaller independent publishers break into the game.

It also forced comics retailers to operate more efficiently. They couldn’t return as much of their inventory so they had to order smarter. Hibbs says that this is still giving comic book stores an edge: part of Amazon’s advantage over brick and mortar book stores is it can sell books for lower than their “list price.” But comic books have a lower list price stores have been doing this for decades — the average price of a new issue of a serialized comic book is still under $4.

Brian Hibbs, Comix Experience founder and owner

Hibbs entered the business in the 1980s when he was a teen. At 16 he got a job at a comic book store and slowly came to appreicate he had the “stereotypical worst boss ever.” The management was disorganized and the paychecks were unreliable. Hibbs says he remembers thinking, “I could do a better job than this guy!” So he decided he would try. In 1989, at the tender age of 21, he opened Comix Experience with little more than $10,000 and his private comic collection on the stands. In 2013 he expanded the store to a second branch, bringing it up to break even in less than a year.

Hibbs says that, on top of pricing, are plenty of other reasons why the Internet hasn’t put him out of business. For one, video, music, and book brick and mortar retailers are struggling because people can get a comparable (if not better) product — cheaper and more easily online. He says this isn’t the case with comics, because comics lose more than any of these other media in digitization. “Comics become harder to process once you change the parameters of the page,” he says. “The unit of the comic is not the individual panels. The magic and the alchemy of comics happens in the margins.”

He gives the example of the famous Peanuts strip, in which Charlie Brown runs to kick a football held by Lucy, and ends up flat on his back. She pulls it away in between panels. “At no point do you ever see Lucy pull the ball away,” Hibbs says. “You never see Lucy, going, ‘Haha, you don’t get to kick the ball!’” That all happens in the margins, and can fall flat depending on how a page is formatted.

For another, comics fans who have subscriptions to serialized comic books can get the latest issue from stores sooner than if they got the issue delivered to their house. And unlike with books, or even with films or music these days, this is something a lot of comic book readers really care about.

Here’s why: Because serialized comics come out weekly, 52 weeks a year, some readers become very invested in the characters and plots. It’s like Game of Thrones, if the season was year-round. Getting your hands on a comic book the moment it comes out doesn’t just mean you get to read it sooner, it means you get to participate in discussions about the latest developments in the overarching plot.

Hibbs says it’s this social component that gives comic book stores their biggest edge. “The first and most obvious reason is that its a social experience to come to a comic book store,” he says. There are few better places to discuss comics than comic book stores themselves, where people love comics, and people like Hibbs and Fiveash are eager to discuss the artistic merits of what you just read and what you’re about to read.

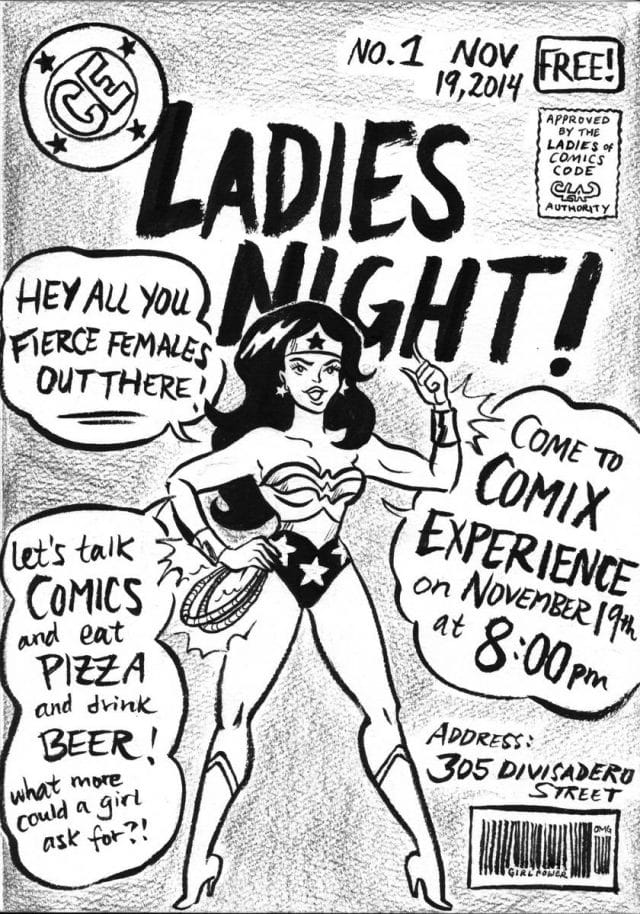

Flyer for a comics fan meetup at Comix Experience

That Hibbs believes this is the core to his success is reflected in his business plan. He says that the next hurdle for Comix Experience is adapting to San Francisco’s latest minimum wage hike, which will require making $80,000 more in sales per year. His solution is to turn the store into more of a comics salon, with the Graphic Novel of the Month Club. For $20-$25 a month, participants will get the staff-selected best new graphic novel of the month, and an invitation to a book club meeting to discuss the novel, which will include the books’ artists and authors.

Labor of Love

“It has been said that ‘there’s no room for sentiment in big business,’” comics retailer Brain Hibbs wrote in 1991. “We are perhaps the only big business that was created by fandom, for fandom.”

According to him, that hasn’t changed, and it’s the key to understanding comics retail. In the end, its a labor of love, and that keeps costs down. It means that he generally can count on loyal customers to buy the inventory he carefully ordered. It means there’s a market for things like the Graphic Novel of the Month Club, which an outsider might think would only appeal to the nerdiest of the comic book nerds (Higgs says that in the third week of selling memberships, they got 40% of the way to their goal.) It means he can get great employees for relatively cheap — they’re just happy to have their passion for comics subsidized by the market.

“I could certainly be making more money doing something else,” he says. “I could go get a straight job, but I really, really like what I do. My employees really, really like what they do. We wake up in the morning and go, ‘I get to go to work!’”

This post was written by Rosie Cima; you can follow her on Twitter here. To get occasional notifications when we write blog posts, please sign up for our email list