“Individual days off during the week seem to fall very far short of the experience of shared weekends.” — Young and Lim, “Time as a Network Good”

Recently, this author tried to convince her friend Graham into going to sleep early on a Friday night so that they could leave at before dawn on a hike the following morning.

“I don’t know,” he said. “It’s a Friday. That’s my only weekend night. I try to keep it open.”

“What are you talking about?” this author asked. Graham was a high school tutor and, at the time, had set his own schedule: he worked four days a week, Sunday through Thursday. By this author’s calculations, this gave Graham a three day weekend, and three weekend nights. “You have a longer weekend than most people, while most of us suckers are stuck at work.”

“Yes,” he said, “and you suckers matter more than you might think.” He explained that a Friday night was way more valuable to him than a Wednesday or a Thursday because his friends could come out drinking with him. He said it was actually pretty “rough.”

“Whatever,” this author shrugged, and probably called him a “wimp” and his setup “cushy.”

But research now suggests that Graham was not, in fact, full of shit.

Even the Unemployed are Living for the Weekend

As you might expect, science knows just as well as the rest of us that most of us working stiffs are, on average, much happier on the weekend. Which is one reason why Graham gave himself so many days off. But was that wise? As the authors of “Time as a Network Good: Evidence from Unemployment and the Standard Workweek” asked: “How much of the enjoyment of the weekend can be gained by not working on weekdays?”

Well, researchers discovered that the unemployed — who have every day off — are also statistically happier on weekends than they are on weekdays. “Because the unemployed do not go to work, one might think that weekends lose their meaning,” one of the researchers said. “That is not the case. The unemployed get about 75 percent of the boost in well-being on weekends that workers get.”

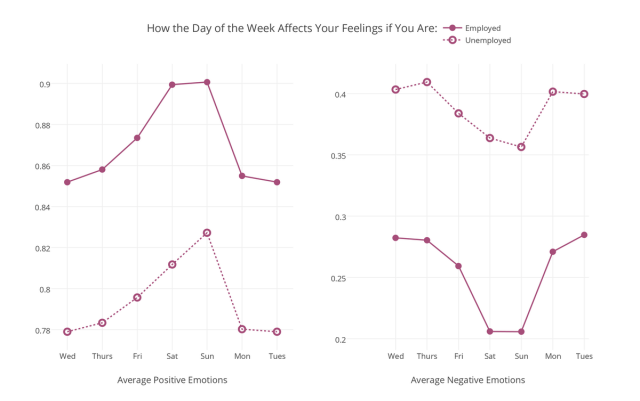

Since 2008, the Gallup polling company has been cold-calling people every day and asking them a battery of personal questions. Gallup conducts 1,000 interviews a day and the interview contains questions about “emotional well-being” and “labor force status.” The researchers took over a million of these responses, then grouped them by employment status and day of the week.

Priceonomics; data via Young and Lim

They found that, whether or not you’re employed, you’re more likely to say you “smiled or laughed,” experienced “enjoyment,” or experienced “happiness” on a weekend than on a weekday. And on a weekend, you’re less likely to say you experienced a lot of “worry,” “sadness,” “stress,” or “anger.” Perhaps unsurprisingly, unemployed people appear to be more stressed and laugh less, on any day, than the comfortably employed.

The researchers think this ‘boost’ the unemployed experience is probably due to the fact that they get to spend more time goofing off with us working stiffs on weekends.

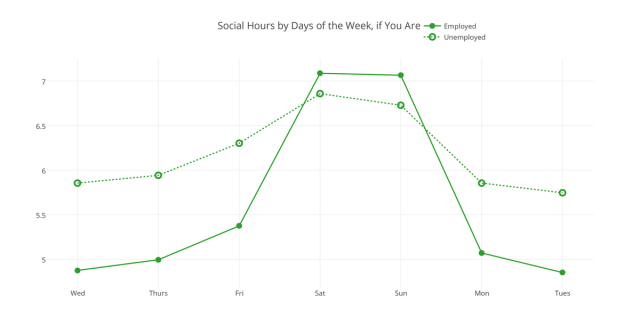

The researchers also used American Time Use Survey data, and Gallup data, to figure out how many hours people spent socially with friends and family each day of the week. As the researchers note, the “weekend effect” is robust here, too, as everybody spends more time socializing on the weekend. In fact, employed people actually spent more social time on the weekends than the unemployed.

Priceonomics; data via Young and Lim

They found that increases in weekend social time accounted for “nearly half” of the positive effect weekends have on well being.

That leaves the other half of the effect unaccounted for, but the researchers expect that it’s also social, in some broader sense. There are a lot of benefits to aligning your free time with the social norm: venues book better concerts on weekends, people throw better parties, and as the study showed, people are generally happier. As the researchers argue in their paper, there are even more varied effects:

“The efficacy of things like factory production, political protests, church gatherings, Christmas parties, family dinners, and football games depends on how many people show up for them. When an additional person goes to church, that person creates a positive externality for other churchgoers, who can enjoy a more vibrant religious experience. The more family members show up for Thanksgiving dinner, the more a sense of family is created.”

“We live in a ‘time famine’ era,” they write in the paper’s introduction. But while most people think of the problem as, “there are simply not enough hours in the day,” that isn’t the whole picture. Like it or not, most of us wouldn’t have much more fun playing hooky. “The essential characteristic of the weekend is not just the having of a day off but rather that other people have the day off.”

This post was written by Rosie Cima; you can follow her on Twitter here. To get occasional notifications when we write blog posts, please sign up for our email list