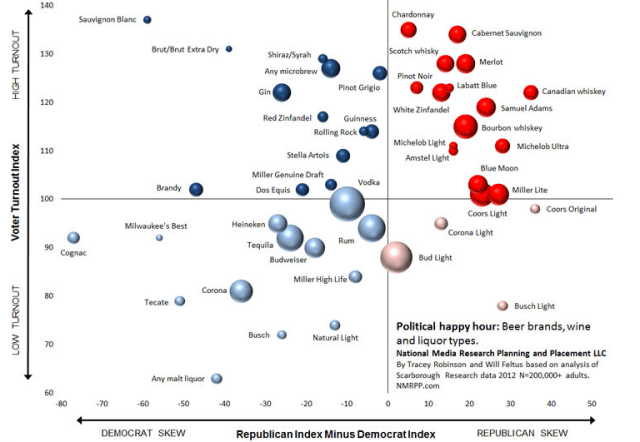

The Politics of Beer. Source: National Media Research, Planning, and Placement

Who wouldn’t want to know what their favorite beer says about their politics?

Thanks to the above chart created by National Media Research, Planning, and Placement (NMRPP), millions of Americans have been able to confirm their hunch that Democrats drink microbrews while Republicans choose light beers, that bourbon does in fact skew conservative while cognac is for liberals, and that drinkers of malt liquor and light beers don’t turn out to vote nearly as strongly as imbibers of wine on the left and right.

NMRPP helps Republican politicians and causes buy advertising campaigns that reach their right-leaning (or centrist) target audience, so it is important that its employees understand the preferences of different blocks of voters — particularly voters’ favorite television channels, newspapers, and radio stations. To gain a little publicity, NMRPP has shared charts like the one above with the New York Times and the Washington Post that compare Republicans’ and Democrats’ preferences for everything from cars to restaurants to social media sites. Other organizations and publications have followed suit.

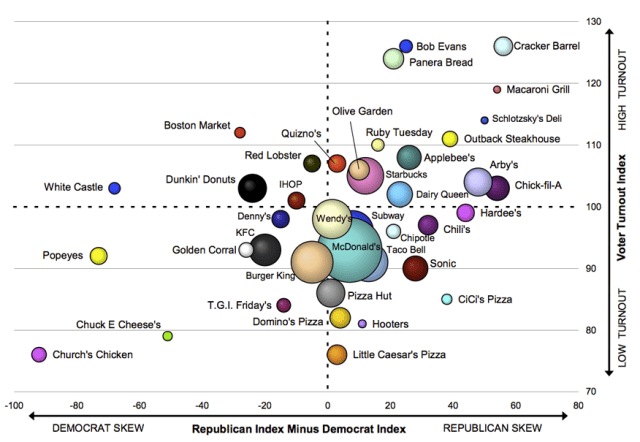

Nearly every time, the graph has gone viral; media sites and personal blogs republish the charts with headlines like “What Your Favorite Sports Say About Say About Your Politics,” or “The Politics of Movies.” People love these things. It’s fun to discover that M&M’s are a bipartisan obsession and that the audience for Fox News and golf is really as dominated by Republicans as you think.

The Politics of Restaurants

Source: NMRPP via the New York Times

Underneath the light-hearted analysis, however, lies a reminder of a depressing truth: politics — the process which ultimately determines whether bridges get built, banks get bailouts, and young men and women get sent to die in foreign countries — is all about identity. Identifying as a Democrat or Republican isn’t an expression of preferences about certain policies and governing styles; it’s a way of life.

One way political scientists conceptualize politics is as a process of defining “us” versus “them.” The tribal nature of political parties isn’t as obvious in the United States as it is in countries like Iraq that feature almost exclusively ethnic-based political parties, but as all these viral political identity charts remind us, it’s still as obvious here as Sarah Palin describing her political constituents as “the real America.”

One of the most stable observations in American politics is the dependability of the vast majority of Americans inheriting their political affiliation from their parents. Even as they describe how voters’ preferences can change in response to evolving mores and events within presidential campaigns, Richard G. Niemi and M. Kent Jennings write in the American Journal of Political Science that “among adults, both young and old, ‘realization’ of parents’ partisan or independent positions remains a dominant mode.” Children may always seem to buck their parents’ beliefs in a liberal direction, but even in 1970s America, “this relative stability and inheritability was preserved.”

The fact that politics is used to define identities in opposition to other groups is not very helpful for decision-making and cooperation — a fact that foiled President Obama’s promise that “I don’t want to pit Red America against Blue America. I want to be President of the United States of America.” It’s also why facts have about as much a place in debates over politics and national policy as they do in arguments over whether San Francisco or Los Angeles is a better city: Defending the banks from the criticism of Occupy Wall Street isn’t about the merits of the bailout; it’s about defining yourself in opposition to those yahoos in Zuccotti Park.

Put another way, there’s no good reason why so many people should be completely set on their views about immigration policy, social safety nets, the gold standard, or any of the countless issues that experts regularly express uncertainty over. Yet they are completely certain and unwilling to change their mind. And that is because everyone like them thinks the same, and if they were to change their mind, they might also have to change everything about their life: drink microbrews instead of Coors Light, cheer on FC Dallas instead of the Dallas Cowboys, and learn to use Reddit. No one wants to turn their back on the tribe; betraying your political affiliation can be as scary as walking away from the campfire to wander in the wilderness.

This post was written by Alex Mayyasi. Follow him on Twitter here or Google Plus. To get occasional notifications when we write blog posts, sign up for our email list.