“‘I’ am not a writer. ‘I’ am what is left over from James Tiptree Jr., a mindless human female who ‘lives’ from day to day…”

— Alice B. Sheldon

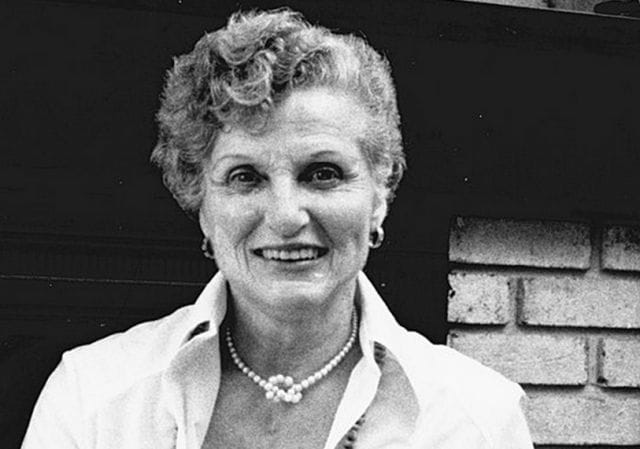

![]()

In the late 1960s, a brazen new voice emerged on the science fiction scene. Witty, confident, and timidly brilliant, the newcomer quickly amassed a cult following for his stories, ranging in topic from intergalactic affairs to alien copulation. No sci-fi author had ever quite written in such a way that was at once authoritative and coy, grandiose and self-aware.

His name was James Tiptree, Jr.

Over the next decade, Tiptree became something of a legend in his genre, cultivating a steady stream of highly nuanced short stories which consistently won him praise from miserly critics. He established, through written letters, intensely personal relationships with prominent authors, publishers, and public figures while at the same time remaining incredibly secretive. Nobody ever saw his face, or spoke with him on the phone; his agent was denied access to in-person meetings. Speculations were rampant, most of which penned Tiptree as a dapper secret agent of some sort, undeniably masculine.

But James Tiptree Jr. held a deep, calculated secret: “he” was a woman named Alice Bradley Sheldon — and she would decimate the stereotypes of gendered writing.

The Incredible Life of Alice B. Sheldon

Alice Bradley Sheldon was born August 24, 1915 in Chicago’s intellectually burgeoning Hyde Park neighborhood. Her father was a lawyer and naturalist, her mother, a travel writer; both were constantly mobile, and young Alice Sheldon spent much of her early life traveling around the world. In 1921, the family ventured to central Africa, where Sheldon’s parents established themselves as cultural and geographical explorers. Sheldon’s mother, Mary Hastings Bradley, published a book, Alice In Jungleland, chronicling her daughter’s adventures in remote corners of African society; the tales made the child a public figure.

Early on, Sheldon’s mother was a huge inspiration for her. Later, she’d describe her as a “dazzling and formidable ‘queen bee’…gifted, beautiful, [and] accomplished — a superb shot and brave endurer of considerable hardships.” A strong, independent “heroine,” Mary dispelled the notion that a women should be confined to homemaking, and she instilled a sense of wonder and tameless possibility in her daughter.

At 19, Sheldon was wed — she felt it was her “duty as a daughter” — but the marriage dissolved six years later, and she experienced a deeply personal creative birth. From 1941-42, she served as an art critic for the Chicago Sun, painted, and contributed graphic artwork to a variety of publications. Then, in 1942, she joined the Air Force.

The sole female photo intelligence officer in her unit, Sheldon was tasked with flying over German territory and taking aerial photographs of army bases to determine where the Nazis had mass weapons stored — a duty that played an instrumental role in the eventual defeat of Hitler. She was promoted to major, a rare feat for a woman at the time, and was sent on an assignment to Paris; there, she met her second husband, Huntington Sheldon, and adopted his surname.

In the early fifties, the couple was recruited to join the C.I.A. For several years, Sheldon toiled as an undercover agent, an ostracized woman in a male-dominated field (her husband would later serve as the Director of the agency under Presidents Truman, Eisenhower, and Kennedy).

But Sheldon’s curious spirit wasn’t quenched, and by 1955, she’d left the force to pursue a higher education; by 1967, she’d earned a Ph.D. in experimental psychology at Washington University. Then, for kicks, she began to write science fiction.

The Birth of James Tiptree Jr.

Sheldon had published work earlier in her career (ie. “The Lucky Ones,” The New Yorker, 1946), but never considered trying her hand in science fiction, a genre that was largely male-dominated. When she garnered an interest in the late 1960s, she had two precautions in mind: she had to protect her academic reputation, and she had to keep her identity as a woman under wraps so as not to isolate her largely-male audience.

Sourcing the name “Tiptree” from a jar of marmalade, and adding “Jr.” at the behest of her husband, Alice B. Sheldon had a new moniker: in 1967, at 51 years old, she became James Tiptree Jr., a rogue, secretive science-fiction author.

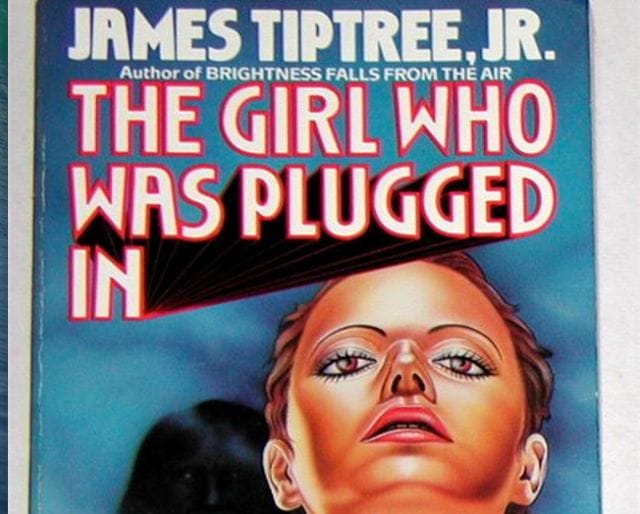

Tiptree’s first story, “Birth of a Salesman,” debuted in the March 1968 issue of Analog Science Fiction, and was widely successful; in the ensuing months, it was followed by a succession of three more in If and Fantastic (two other Sci-Fi rags). Many of the author’s early stories pulled from experiences in the C.I.A. and grappled with the themes of bureaucracy — paranoia, politics, espionage — often set in space, or alternate dimensions.

Often, Tiptree’s themes were dark and troubling, and subtly spoke to “his” hidden identity as a woman. His characters were often portrayed as spiritually alienated; one critic at the time noted the author’s propensity to “deal directly with the death of the spirit, or of all hope, or of the [human] race.” In Tiptree’s “Painwise,” the protagonist undergoes a procedure which makes it impossible to feel pain, a curse that ends up being unbearable. Another story, “Love Is the Plan the Plan Is Death,” explores the theme of biological determinism, and features hapless characters that are unable to exert free will.

Most overtly, Tiptree’s work honed in on the feminine mystique. In his most famous work, “The Women Men Don’t See,” two women frantically attempt to escape a male-dominated Earth. The story’s narrator, a man, is disgusted by the two women, who he finds unwilling to “fulfill stereotypical female roles,” and he fails to acknowledge their societal isolation. In “Houston, Houston, Do You Read?,” a colony of female clones must endure the sexual onslaught of three male time travelers.

By the mid-1970s, Tiptree had gained adoration from critics, publishers, and fans; despite this, the supposed man remained shrouded in a veil of mystery. Only Sheldon and her husband knew Tiptree’s true identity — everyone else was left to speculate. And speculate, they did. Despite Tiptree’s penchant for exploring feminist themes and his liberal exploration of sexuality, society seemed to wholly agree that the author was a “particularly macho male.” When a small inquiry arose as to whether or not Tiptree could be female, prominent figures in science fiction unanimously disagreed, including famous science fiction writer Robert Silverberg:

“It has been suggested that Tiptree is female, a theory that I find absurd, for there is to me something ineluctably masculine about Tiptree’s writing…[He’s] a man of 50 or 55, I guess, possibly unmarried, fond of outdoor life, restless in his everyday existence…a man who has seen much of the world and understands it well.”

In Tiptree’s Warm Worlds and Otherwise, a published collection of stories, Silverberg elaborated on the “absurdity” of the notion that Tiptree could possibly be female. “The author of these stories,” he wrote, “can only be a man.” Though second-wave feminism continued to broaden the rights and roles of women through the 70s, Tiptree’s contemporaries refused to believe that a woman could’ve possibly written such works of genius. But soon, they’d be proven wrong.

The Shame in a Name

In 1976, at the apogee of Tiptree’s career, reports surfaced that his mother, Mary Hastings Bradley, had passed away in Chicago. When fans who wished to pay their respects dug into the matter, what they found shocked them: a small, local obituary for the woman listed one only surviving family member, an Alice B. Sheldon.

After years of speculation and secrecy, the literary world had finally uncovered James Tiptree’s true identity: the “unmistakable man” was a woman.

Silverberg and other critics who’d staunchly argued that Tiptree’s writing was “inherently male” faced public embarrassment. Sheldon herself, who’d for years been reveling in her disclosed status, had to confront the challenge of explaining herself, which she later did in Asimov’s Science Fiction:

“A male name seemed like good camouflage. I had the feeling that a man would slip by less observed. I’ve had too many experiences in my life of being the first woman in some damned occupation.”

Having spent her entire life in male-dominated arenas — the Air Force, the C.I.A., academia, and, finally science fiction writing — Sheldon had become a persona who could say all of the things she felt she couldn’t as a woman. Once outed, Sheldon didn’t feel a sense a liberation. Though her publisher was supportive, Sheldon couldn’t shake the feeling that any subsequent friction was a result of transitioning from a perceived male writer to a female writer. In a journal entry, she writes of her tremendous sense of alienation, and a loss of creative power:

“‘I’ am not a writer. ‘I’ am what is left over from [James Tiptree] Jr., a mindless human female who ‘lives’ from day to day … ‘I’ haven’t a story in my head — all that went to J.T. Jr…I had, through him, all the power and prestige of masculinity, I was — though an aging intellectual — of those who own the world. How I loathe being a woman … Tiptree’s ‘death’ has made me face … my self-hate as a woman.”

For some time, Sheldon continued to publish as James Tiptree, Jr., but her confidence didn’t shine as it once did and her success subsequently dipped. In the early 1980s, she wrote two novels exploring her usual themes, neither of which was well-received. Gradually, the formidable author faded from the science-fiction scene.

On May 19, 1987, at 71 years of age, Sheldon awoke in the middle of the night, loaded a gun with two bullets, and shot her blind, bedridden husband in the head while he slept. Then, she laid down beside his dead body, clasped his hand, and took her own life. In her book, James Tiptree Jr.: The Double Life of Alice Sheldon, biographer Julie Phillips clarifies that Sheldon had written a suicide note years earlier, and that the couple had planned their joint suicide. The dark and twisted elements in Sheldon’s stories, it turned out, were a sign of her own unsettled state.

![]()

Throughout the 20th century, a multitude of female writers attempted to shield their sex using male monikers. CJ Cherryh (Carolyn Janice Cherry), Vernon Lee (Violet Paget), CL Moore (Catherine Lucille Moore), Paul Ash (Pauline Ashwell), and many other prominent science-fiction authors felt the need to change their names to be marketable — even Joanne Rowling (JK Rowling, of Harry Potter fame), whose publisher urged the switch “so as not to turn off young boys.”

Sheldon’s case was particularly unique. She not only disbanded the theory that a woman’s writing style is discernibly different than that of a man, but chipped away at gender stereotypes and made a strong case for the fortitude of women in science-fiction. Though she achieved fame as a man — James Triptee, Jr. — Alice B. Sheldon gained permanence as an everlasting manifestation of the internal struggles female creators face.

This post was written by Zachary Crockett. Follow him on Twitter here, or Google Plus here