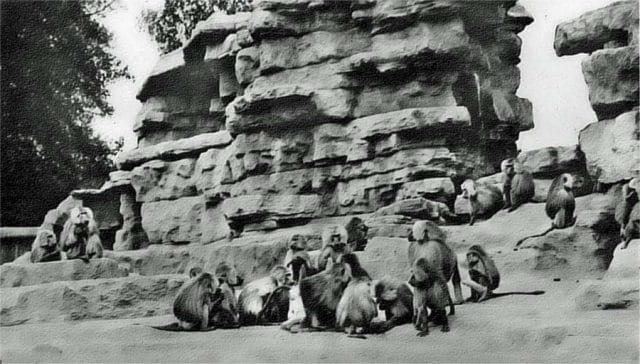

Photo from Malcolm Peaker

***

In 1932, Solly Zuckerman sat down to write a book about a baboon massacre at the London Zoo.

The carnage in question had started seven years earlier when the Zoological Society of London opened a new baboon exhibit. The enclosure, called “Monkey Hill,” was state-of-the-art: an open-air rock cliff with simian-friendly amenities designed to keep the resident primates happy and healthy.

But something had gone terribly wrong.

As soon as the first batch of hamadryas baboons were ushered onto the artificial rock face, war broke out. By the end of the decade, two-thirds had been killed.

The seven-year bloodbath was a hit with the viewing public, and the misdeeds of these murderous monkeys made a splash in papers on both sides of the Atlantic.

For Zuckerman, who dissected and studied animal carcasses at the zoo, the violence provided an important insight into primate behavior. Ape and monkey society is built on violence and sexual dominance, he theorized. Humanity’s closest relatives were creatures of chaos, lust, and slaughter. This insight launched Zuckerman’s career and defined the early scientific field of primatology.

For many, the theory also offered an appealing explanation for human behavior. In political science, psychiatry, and the popular press, the slaughter at Monkey Hill was taken as evidence of the inherent depravity of humanity.

There was just one problem: the science was bunk. Baboons do not routinely butcher one another in the wild, nor do all primates behave like hamadryas baboons.

Primatologists have long since dismissed Zuckerman’s theory of primate behavior. But for decades, the mistaken lessons of Monkey Hill defined primatology, permeated popular culture, and contributed to a widespread view of humanity as a species on the brink of mayhem.

The Benefits of Outdoor Living

Monkey Hill was supposed to save the baboons.

Until the 1920s, the London Zoo housed most of its animals indoors, in the dark, and behind bars. But the sickly, sad-looking creatures depressed the zoo visitors and dropped dead of preventable illnesses at alarming rates. The primates were of particular concern. Pneumonia, tuberculosis, and vitamin-D deficiency were the scourge of the Monkey House.

Taking a cue from German zookeepers, the London Zoological Society designed an outdoor enclosure called Monkey Hill in 1924—a place where primates could roam about and live as if they were in their native habitat. Well, nearly. The zookeepers used shelters, heaters, and UV-lights to combat the perennial gloom of fog-swaddled London.

As science writer Jonathan Burt explains, the open-air exhibit was “intended to showcase the benefits of outdoor living for animal health.” Plus, he adds, from behind the 12-foot outer wall that surrounded the enclosure zoo, visitors were afforded a much better show.

They got one.

In 1925, a shipment of ninety-seven hamadryas baboons arrived by boat from the Horn of Africa. They were all supposed to be male. As Jane Goodall’s biographer Dale Peterson writes, the zoo’s gender preference was “based on the idea that the males—big and dramatically fanged and caped, with pink buttocks—would appeal to a zoo-going public more than the smaller and less gaudy females.” But whether by neglect or indifference, six females were included in the shipment. The result was a bloodbath.

Once the exhibit opened, the males immediately went to war over access to the females. With the former outnumbering the latter 15-to-1, the competition was ferocious. Caught in a constant tug-of-war between dozens of brawny, sharp-fanged males, most of the females were killed over the coming months. Even so, the males fought over their bodies. The violence was sometimes so fierce that zookeepers had to wait days before they could scale Monkey Hill and retrieve a carcass. Within two years, nearly half of the baboons were dead.

A male hamadryas baboon. Photo by Sonja Pauen.

But rather than remove the remaining females from the enclosure, the Zoological Society of London thought that they could quell the violence by adding more. Just as the fighting began to simmer down in 1927, the zoo introduced 30 additional females and five adolescent males. The violence exploded anew.

By 1931, 64% of all the males and 92% of the females that had been brought to Monkey Hill had died. While some of the males had died of disease, virtually all of the females died violent deaths. Of the 15 infants born in the enclosure, only one managed to survive.

This all came as a shock to the zookeepers. Instead of a sanctuary, they had inadvertently created a fighting pit—a gladiator arena with sex. And there was a lot of sex. In 1929, one member of the Zoological Society worried that the constant baboon copulation—violent, polygamous, and occasionally necrophilic—would have a “demoralizing” effect on the public.

Just the opposite was true. The sex and violence on Monkey Hill was a draw for zoo visitors. The tabloid press in England took a prurient interest in the sorry state of the females on the hill, with one describing “meek, subdued, tractable creatures” who “live on the leavings and take life sadly.” In 1930, even Time magazine profiled the “wife-stealer” primates at the London Zoo.

The same year, the zoo superintendent finally removed the surviving females. It was a moral choice, but not a shrewd business decision: the violence dropped along with attendance at the exhibit. To at least one tabloid, the conclusion was obvious: “men are a peaceable race, once you eliminate the women.”

This was only the first of many flawed conclusions to be drawn from Monkey Hill.

Red in Claw and Fang

When Solly Zuckerman was hired by the London Zoo to dissect baboon carcasses, he came with experience.

Born in South Africa, where baboons were regarded as a pest, he had spent his teenage years shooting the animals for bounty and dissecting their bodies for fun. This odd adolescent hobby notwithstanding, Zuckerman had very little experience observing how baboon troops behaved in the wild. He wasn’t alone. Very little was known about the social lives of nonhuman primates.

The exhibit at Monkey Hill gave Zuckerman an opportunity to watch a group of monkeys being monkeys. What he saw, both on the hill and the autopsy table, was a revelation. After a few years of observation, lab work, and a short stint in the field back in South Africa, Zuckerman published his grand theory on primate society: The Social Life of Monkeys and Apes.

According to Zuckerman, life in the jungle is nasty, brutish, and short. All “sub-human” primate relationships fit into strict, male-dominated hierarchies that are maintained through coercion, intimidation, and bloodshed. The only thing that prevents the chest-thumping testosterone fest from descending into absolute chaos is the prospect of copulation. Whenever conflict arises within a troop, females offer sex to paper things over. When that fails, the alpha males resort to murder. Such is the way not only of baboons, wrote Zuckerman, but all non-human primates.

Male hamadryas baboons are considerably larger than the females. Photo by Ruben Undheim.

This conclusion was based on his observations at Monkey Hill, but it was also, according to Zuckerman, an inescapable result of primate biological characteristics. Males dominate females because they are bigger, and they keep females as permanent members of their troops because they are fertile year-round. “Reproductive physiology is the fundamental mechanism of society,” he wrote. Violent behavior is baked in.

The Social Life of Monkeys and Apes was published in 1932 (over the objections of the zoo management, who found Zuckerman’s lengthy descriptions of baboon sex unseemly). This Clockwork Orange-view of ape and monkey behavior dominated the field of primatology for the next three decades.

To his credit, Zuckerman was careful to say that his theory only explained non-human primate behavior. But not everyone got the memo. Social theorists, journalists, and the public at large took Monkey Hill and Zuckerman’s grand theory as a description of humanity unencumbered by law and social mores.

In their political tract, Personal Aggressiveness and War, the English politician Evan Durbin and psychologist John Bowlby used the story of Monkey Hill as evidence that human beings had a natural propensity towards war. “Fighting is infectious in the highest degree,” they wrote in 1938. “It is one of the most dangerous parts of our animal inheritance.”

This must have been a compelling conclusion at the time. This was the same year that Germany annexed Austria, laying the groundwork for the Second World War.

In the following decades, scientists came to doubt Zuckerman’s theory. But in popular culture, the idea stuck around.

In 1957, the popular science magazine, New Scientist, wrote the “sadistic society of the totalitarian monkeys” on Monkey Hill and drew a parallel to the mutiny on the Bounty. This was the infamous maritime rebellion in which men, adrift upon the lawless sea, seized the HMS Bounty and settled as outlaws in the South Pacific. Some 30 men took up residence on Pitcairn Island in particular.

“In 10 years all the men had been killed except one,” the article explained. “The principal difference between Pitcairn Island and Monkey Hill seemed to be that the abnormal social conditions resulted more lethally for the males in the human colony and for females in the sub-human colony.”

The public’s infatuation with this theory of the violent primate came at an odd time. As the primatologist Shirley Strum and William Mitchell wrote in the 1980s, “just as specialists were abandoning [Zuckerman’s] baboon model, the popular press and nonspecialists interested in interpreting human evolution adopted and championed that view of primate society.”

These nonspecialists included writers like Robert Ardrey, who began championing the so-called “killer ape theory”—the idea that the evolutionary success of homo sapiens was the result of our inherent aggression. Thus, 2001: A Space Odyssey depicts the “dawn of man” as an early hominid learning how to use a weapon and beat a cow skeleton to bits in a fit of rage.

The idea that the violence at Monkey Hill reflected our natural state contributed not only to a grim view of human nature, but of the natural world as a whole.

“The hamadryas colony at the London Zoo reinforced a widespread belief in an unconstrained Darwinian struggle for existence,” write Carl Sagan and Ann Druyan in their 1993 book, Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors. “Many people felt that they had now glimpsed Nature in the raw, a brutal Nature, red in claw and fang, a Nature from which we humans are insulated and protected by our civilized institutions and sensibilities.”

There but for the grace of God, law, and authority go we to Monkey Hill.

Lab versus Field

But, of course, this was all based on bad science.

As anyone who has watched nature documentaries on bonobos can tell you, not all primates are patriarchal killing machines. And even the male-centric hamadryas baboons only live up to Zuckerman’s hyper-violent description in certain, artificial circumstances.

Circumstances like Monkey Hill.

First, there was the issue of space. A typical troop of 100 baboons in the scrublands of Ethiopia will range over an area of roughly 50,000 square meters. The enclosure at the London Zoo was a little over 500 square meters, nearly one-hundredth the size.

Beyond the crowding, the exhibit’s extreme gender lopsidedness was far from anything that might be observed in the wild. Hamadryas baboons are the only primate species besides gorillas that maintain harems: family units that consist of a single male and up to ten females and infants. These harems form together into clans. Overtime, these clans establish a clear hierarchy of dominance. If that hierarchy is violated, the culprit will be severely punished by the various males.

But the London Zoo had penned nearly one hundred males with no prior social ties together with half a dozen unfortunate females.

In short, trying to generalize about primate behavior based on Monkey HiIll would be like trying to learn about human nature by watching a prison riot.

Still, Zuckerman’s grand theory of primate behavior had staying power because it tapped into a key bias within the biological sciences: work in the lab outranked research in the field.

When other primatologists, like Clarence Ray Carpenter, offered contradictory accounts of monkeys in Panama notably not murdering one another with abandon, much of the research community looked down upon these observations as second-class science. How could observations made by a sweaty, exhausted, mosquito-bitten field worker compare to the conclusions of a sober-minded scientist in the lab?

Solly Zuckerman, 1943.

It wasn’t until the early 1960s that Solly Zuckerman’s theoretical superstructure finally came toppling down.

By then, Zuckerman had been knighted, had served as chief scientific adviser to the Ministry of Defense (alongside primate anatomy, he took an interest in ballistics), and was serving as Secretary of the London Zoological Society.

As an elder zoologist, he was particularly dismissive of a young “amateur” scientist named Jane Goodall. With few credentials to her name, Goodall had spent months observing chimpanzees at Gombe National Park in Tanzania. This was an “act of radical immersion” that was unheard of in the primatology community, writes Goodall’s biographer, Dale Peterson. Returning from East Africa, she published findings in which she observed that chimpanzees, unlike their baboon cousins, did not form harems. More generally, they didn’t seem to behave as the violent patriarches Zuckerman insisted they were.

Though Zuckerman never admitted that he was wrong, in the words of Dale Peterson, this showed that primate life was not solely a “masculine melodrama on the themes of sex and violence.” Through field observations, Goodall and a new generation of primatologists, showed that primate behavior is complex, varied, and heavily influenced by environment. It was, in other words, immune to the sweeping generalizations put forward by Zuckerman.

The end of the Monkey Hill era, writes Peterson, marked “the debut of primatology as a modern science.”

The Moral of Monkey Hill

Humans are suckers for a good animal allegory.

When Ivan Pavlov learned that he could trick his dog into salivating at the sound of a bell, “Pavlov’s dog” became cultural shorthand for the mechanical naiveté of human behavior.

When B.F. Skinner discovered that birds could be taught to bob their heads in a certain way to receive food, “Skinner’s pigeons” likewise became a reference for the universality of human superstition.

And when animal behaviorist John Calhoun created an overpopulated mouse enclosure at the National Institute of Mental Health—and watched as the rodents descended into a “behavioral sink” of asexualism, cannibalism, and violence—John Calhoun’s “rats of NIMH” became a modern parable about overcrowding in urban centers.

As Eric Michael Johnson writes in Scientific American, Monkey Hill is now its own kind of a parable.

The case of Zuckerman and the baboons of London, he writes, is “a zoological case study that reveals the danger of embracing a faulty assumption about ‘natural’ behavior.” The baboons on Monkey Hill were not emblematic of all apes and monkeys. They certainly weren’t emblematic of humans. Trapped, overcrowded, and placed within an unnatural social environment, they weren’t even emblematic of their own species.

If there is a lesson to be learned from the story of Monkey Hill, it is that we are too eager to learn lessons from the animal kingdom.

Our next article looks at prison data to show that the reduction in mass incarceration in America is a glitch. To get notified when we post it → join our email list.

![]()

Announcement: The Priceonomics Content Marketing Conference is on November 1 in San Francisco. Get your early bird ticket now.