Photo credit: Erik Hersman

Write-in votes are a uniquely American tradition: nowhere else in the world can you cast a vote for a candidate not included on the ballot.

With two of the least popular candidates ever running for president, Americans may turn to write-in votes. According to CNN, Google searches for “write-in” votes have surged more than 2800% in the past weeks to levels not seen since 2004. Voters are more curious than ever about how to “write in Bernie Sanders” or “write in Paul Ryan” on Tuesday.

No write-in candidate has ever won the presidential race. So do write-in votes matter? We analyzed presidential election results data going back to 1992 to find out, and we discovered that write-in voting is increasingly relevant. Since 1992, the number of people casting write-in votes has consistently increased.

How write-in voting works

Write-in votes are generally a last resort for third-party candidates.

To get a candidate on the ballot, political parties need to meet ballot requirements in each state. The requirements range from 275 signatures in Tennessee to 3% of registered voters in Arizona (about 85,000), and, historically, only the Democratic and Republican parties have had enough support to get access in all 50 states. (Although the Libertarian party recently achieved nationwide ballot access.)

Candidates unable to secure an official slot on the ballot may choose to run as write-in candidates instead. The following map shows that this is legal in some but not all states.

In 2016, most states required write-in candidates to submit a letter of intent prior to the election to request that their write-in votes be tallied. Other states don’t allow write-ins (NV, NM, SD, OK, AR, LA, MS, SC and HI) or have no restrictions on who voters write in (OR, WY, IA, AL, MS, NJ, VT, NH, RI, PA, and Washington D.C.).

In 42 states, voters have the option to select a write-in candidate. And since 1992, more voters have been exercising that option each election.

Since 1992, the percentage of popular votes that were write-ins has quadrupled from 0.03% to 0.12%. That’s a jump from roughly 28,000 to 158,000 votes.

Write-in votes are on the rise, a trend that shows no signs of stopping in 2016.

Who’s getting all the write-in votes?

It’s not Mickey Mouse or Santa Claus getting all these write-in votes. We took a look at the top five candidates with the most write-in votes by election year below.

Americans are not writing in votes for cartoon characters—they are voting mainly for candidates who appear on the ballot in other states. In 2012, for example, Green Party candidate Jill Stein received 4,636 write-in votes as well as 464,991 official votes from the 37 states where she qualified for the ballot.

Only a few Americans wrote in votes for a Republican or Democrat who had been defeated in the primary—like the 6,812 Hillary fans who voted for her in 2008.

We also see that the most successful write-in candidacies of all time have come in the most recent election. Ron Paul received a record 81,699 write-in votes in 2012, which along with his 262,211 ballot votes, earned him 0.27% of the popular vote. In comparison, James “Bo” Gritz only received 8,050 write-in votes and 0.1% of the popular vote in 1992.

Why are write-in votes on the rise?

An increase in write-in votes may be a symptom of decreasing trust in institutions.

According to a recent study, only 1 in 5 Americans say they trust the government, which may be leading voters to support third-party or write-in candidates who make reform their platform. In fact, Ralph Nader’s 2000 campaign, which won nearly 3% of the popular vote, was based on the idea that the U.S. was in a “crisis of democracy” that could only be solved by a broader distribution of power.

The rise in write-ins could also be tied to a rise in independent campaign visibility. Now that Jill Stein has access to most state ballots and more digital impressions and television airtime, a write-in vote for Stein in Indiana (one of the six states she’s not already on the ballot in) seems less like a longshot.

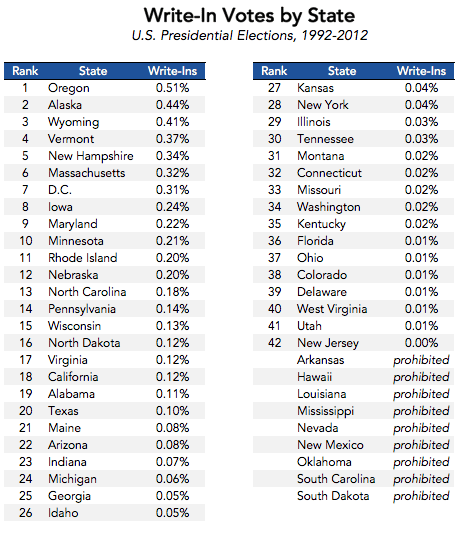

Which voters are driving this increase? Here’s a state-by-state comparison of write-in ballot percentages since 1992:

In general presidential elections, more people cast write-in votes in Oregon (0.51% of votes cast) and Alaska (0.44%) than in any other state. Wyoming and Vermont follow closely at 0.41% and 0.37%. And in recent elections, the rise in write-in voting has pushed that percentage above 0.75% in some of these states.

It’s surprising that New Jersey casts less than 0.01% write-in votes. But the rate at which a state casts write-in ballots may have more to do with their regulations than the political climate or demographics.

The most significant regulation that determines write-in voter rates is the relative ease or difficulty of becoming an official independent candidate listed on that state’s ballot. The below chart ranks states by how many signatures each candidate needs to get on the ballot.

New Jersey residents write in votes less often because it’s really easy to get on the official ballot: candidates only need the signatures of 800 registered voters. Other states, like Arizona, make it difficult, requiring the support of as many as 3% of registered voters.

Do write-in votes matter?

Write-in candidates have won primaries and elections at the state and local level.

Eighteen-year-old Michael Sessions, too young to run on the official ballot, won the mayorship of Hillsdale, Michigan, in 2005 as a write-in candidate. In 2010, Don Shooter won the primary as a write-in candidate and went on to win the general election for a seat in the Arizona Senate. In 2013, Mike Duggan won the primary for mayor of Detroit as a write-in candidate following a court challenge that removed his name from the ballot.

But while it’s not impossible to win office as a write-in candidate, no write-in candidate is poised to win the presidential election vote. The best a third party candidate can hope for is to siphon off enough electoral votes to prevent other candidates from gaining the 270 needed to win (Gary Johnson’s current strategy), in which case, the House of Representatives decides who becomes president.

Even that’s a long shot. Not since 1968 has a third-party candidate been able to secure enough of the popular vote to win a single electoral vote. George Wallace (American Independent party) received 13.5% of the popular vote and 46 electoral votes. But he was still unable to prevent Richard Nixon from hitting the critical mass of 270 electoral votes.

The more likely outcome is damage to either Hillary Clinton or Donald Trump’s campaign.

Supporting third-party or write-in candidates in protest of an unsatisfactory major party candidate may have unforeseen consequences. When Nader received 2.8% of the popular vote during the 2000 election, many cited it as a contributing factor in Al Gore’s loss to George W. Bush. By siphoning off would-be Democrat votes, Nader supporters strengthened the Republican share of the vote.

Recently, Bernie Sanders warned his supporters against casting “protest votes” in his name that could in turn help Donald Trump: “[b]efore you cast a protest vote – because either Clinton or Trump will become president – think hard about it.”

Still, if recent trends hold, Americans will cast more write-in ballots this year than ever.

Our next article investigates whether polygraphs (lie detector tests) actually work. To get notified when we post it → join our email list.

![]()

Note: If you’re a company that wants to work with Priceonomics to turn your data into great stories, learn more about the Priceonomics Data Studio.