Rotisserie chickens look amazing.

When you stroll through the supermarket, looking for a dinner that won’t take too much effort and won’t involve a lot of junk food, you’ll see raw chicken breasts and chicken thighs and whole chickens. They are pale and cold, and turning them into roasted chicken or chicken piccata will take time.

But then there are the rotisserie chickens. They are golden and warm and herb-scented and ready to eat. You could grab one off the shelf this very moment. And even though the deli has done all the work, it doesn’t seem more expensive. It seems like an unbelievable bargain.

Is it any wonder that Americans will buy one billion rotisserie chickens this year, most of those from supermarkets or discount stores with grocery operations?

The price point of rotisserie chickens has captured consumers’ interest almost as much as the chickens themselves. At a typical supermarket, it might cost $7 or $8, the same as a fresh whole chicken in the refrigerator case. Less, in some stores. And the store pays for the herbs and the heat.

Why is rotisserie chicken so cheap? The Internet is full of posts wondering about this, and positing theories. One goes like this: Rotisserie chickens were about to pass the sell-by date in the refrigerator aisle, and the store recoups most of that money by cooking them. Another that has more credence: They’re a loss leader to bring people into the store to buy other things. To some extent that’s true, though stores don’t generally lose money on them.

But neither scenario tells the real story.

Which is this: In most stores, the cooked chickens aren’t any cheaper. They just look cheaper. The per-chicken price favors the deli counter, but the per-pound price favors the refrigerator case.

A lot of chicken went into the previous sentences—14 to be exact, one rotisserie, one from the refrigerator case, from seven separate groceries in California, ranging from Costco to Whole Foods to a Middle Eastern market. After being prepared and cooked, the refrigerated chicken almost always weighs significantly more than the rotisserie option.

Our investigation into the rotisserie chicken industry reveals that it’s not as cheap as people believe. But it is a gift to the lazy and rushed.

The Origin Story

Customers can thank Boston Market—which opened its first store in 1985 in Newton, Mass., under the name Boston Chicken—for the modern rotisserie chicken industry.

It was the perfect strike at the perfect time. Baby boomers were just aging into parenthood. These largely two-parent families had no energy to cook after picking the kids up from daycare, but they were more health conscious than the TV-dinner generation. And the low-fat trend was just getting into swing; people had heard about the supposed evils of red meat and were moving toward chicken as their flesh of choice. Customers snapped up chickens from the booming Boston Market chain on the way home from work, along with a couple of prepared side dishes.

But that meant they weren’t making their traditional stops at the supermarket to pick up something for dinner, and the groceries struck back with rotisserie chickens of their own, at lower prices. The idea was that the store might make little to no money on the chicken, but it would profit from the other items shoppers picked up once they were in the store. A product priced in this fashion is known as a “loss leader.”

The restaurant that started it all. Photo credit: Mike Mozart

Prices on rotisserie chicken have since risen at most supermarkets, but grocery stores still keep prices at a point where they’ll pull in the dinner shoppers, says poultry professor (yes, it’s a thing) Casey Owens Hanning at the University of Arkansas.

And at that, Costco has been that master.

“I can only tell you what history has shown us,” Richard Galanti, Costco’s chief financial officer, told a financial analyst who asked about the pricing in 2015, according to a report in the Seattle Times. “When others were raising their chicken prices from $4.99 to $5.99, we were willing to eat, if you will, $30 to $40 million a year in gross margin by keeping it at $4.99.”

The discount warehouser sold 76 million rotisserie chickens in fiscal 2014, close to 10% of the retail market at the time. Costco has kept the price of rotisserie chickens at $4.99 for as long as Tom Super, the wonderfully named vice president for communications at the National Chicken Council, can remember. It’s the same philosophy that Costco uses for another big draw: the hot dog and soda that have sold for $1.50 since 1985. For these feats, it gets free publicity of all kinds—like this article.

And for Costco, pulling in regular shoppers is a little more of a trick than for supermarkets, according to Super. It needs something special to attract shoppers in the late afternoon on weekdays—which is when most people make their dinner plans—because chances are they have to go out of their way to get to Costco and spend more time getting in and out of the store.

“Some of the things you go to Costco for, you don’t need once a week,” Super says. “In order to attract customers more often, they have chicken or hot dogs or the low prices on gasoline. They don’t put the chickens at the front of the store. You have to walk past the blenders and the big-screen TVs. The guy who stops in to buy a rotisserie chicken for a quick, hot meal might walk past the laptops and say, ‘Maybe I’ll go to the Costco to buy a laptop for my son for Christmas.’ ”

But it’s unclear whether your average supermarket, which doesn’t sell laptops and gas, has the same incentive to offer super cheap chicken.

Cheaper but Smaller

It may seem that rotisserie chickens at your local supermarket are—despite all the extra work the deli has done for you—just as cheap as buying raw chicken. But for the most part, they’re not.

How’s that?

Easy. Though it may not seem that way to the consumer’s eye, rotisserie chickens tend to the small side—maybe two to two and a half pounds. The broiler chickens that sell for the same price are more like four and a half pounds. Even after they’ve been cooked—a process that, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, reduces their weight by a little more than 20%—broiler chickens are still much bigger.

To test out whether rotisserie chickens are still a bargain after you account for their size and reduced water weight, we ran an experiment. We visited seven supermarkets and bought a rotisserie chicken and a raw chicken from each. After draining each rotisserie chicken of the fluid that collects in the container, we weighed them. Then we cooked the raw chickens without giblets according to food writer Mark Bittman’s recipe—a little olive oil, salt and pepper, then roasted in a preheated cast-iron pan in a very hot oven for 15 minutes, with the temperature reduced until they were cooked through—and weighed them.

The goal was to fairly compare the price per pound of each type of chicken, so we added the cost of the oil and seasonings to the overall price of the fresh chicken, as well as the cost of heating the oven and washing up. (Without including the cost of our time, it came to a total of 52 cents.)

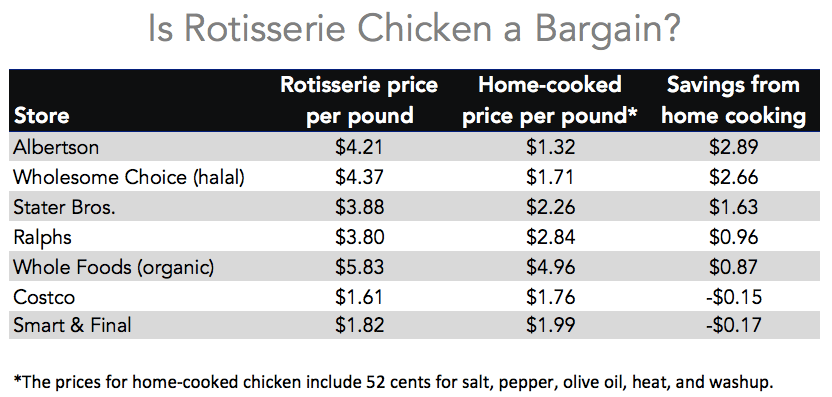

For five of the markets, the homemade chickens were cheaper by about a dollar or more per cooked pound. When chicken was on sale—and it goes on sale a lot—the difference was closer to $2 per pound.

The exceptions were two discount markets, Costco and Smart & Final, where rotisserie chickens were cheaper, but not by much.

Costco, with its famously plump and low-priced rotisserie chicken, as well as Smart & Final, showed large savings for rotisserie, at 15-17 cents per pound. (The two stores offer about equal savings; the difference between 15 and 17 cents here is a rounding error.) Clearly, the chickens are priced to draw customers.

Smart & Final sent this message in a particularly visceral way. At the store we visited, the rotisserie chickens were the first thing the shopper saw walking in the door, sitting together on a hot table dedicated to their savory scents. A big price sign hung above them.

At the other supermarkets, though, the refrigerated chicken was less expensive by a long shot, and buying an uncooked chicken can offer even greater savings when chicken goes on sale—as was the case when we visited Ralphs, a mainstream supermarket chain owned by Kroger. Fresh Foster Farms chickens were on sale for 88 cents a pound, half the usual price. This meant a 4.5-pound chicken, which normally would have cost $8, the same price as the rotisserie chicken, could be fetched for $4.

Super, at the National Chicken Council, agreed that despite their reputation for cheapness, rotisserie chickens are generally more expensive per pound because they’re significantly smaller. Smaller chickens of uniform size can be counted on to fit better in the rotisserie, where they are turned in batches, and to cook at about the same time. If there’s one thing stores want to avoid, it’s an outbreak of food poisoning because some chickens were bigger than others and thus weren’t fully cooked when they came off the spit.

And that, he says, is also part of why chain stores don’t use older chickens from the grocery. The rotisserie chickens are a different production stream, often from a different producer altogether. In most stores, the chicken company isn’t labeled on rotisserie chickens. Is it a Foster Farms “minimally processed” chicken? Or something cheaper, or possibly (though unlikely) better? The provenance is seldom known, even by the people behind the deli counter.

Rotisserie chickens generally come packaged in containers of eight to 12 chickens, almost always pre-injected, fairly uniform in size, and frequently pre-seasoned, ready to pop into the ovens. Other times, Owens Hanning says, the producers include packages of dry-rub in different seasonings—lemon-pepper is a biggie, along with herb-garlic—for store staff to apply to the chicken skin. It’s a rare store for employees to do the chicken prep from scratch, using their own herbs and seasonings—a fact confirmed by workers behind the counters, who, for the most part, didn’t know what was in or on the chickens.

Besides, both Super and Owens Hannings say, stores need a pretty large quantity of chickens to rotisserie every day, far more than would be provided by aging-out chickens in the meat department. And any store that can’t sell off its chickens on time, they say, is a troubled operation with bigger problems than what to charge in the deli department.

But there’s more to consider than just the price. Like most rotisserie chickens, Costco’s and Smart & Final’s cooked chickens are injected with water, salt, and some sort of starch or gum like carrageenan. (Others might use a different but similar additive). The water keeps the chicken moist under the hot lights of a warming table; the salt adds flavor and helps retain the water; and the additives also help maintain flavor and keep the water in the chicken.

Some raw chicken is also “enhanced” with injections of salt water, but not Foster Farms, the label carried in the Costco refrigerator case and many others in the West.

How much water are consumers paying for when they’re buying chicken? The labels don’t say, and Costco refused to comment for this article. But poultry professor Owens Hanning says that for this and most rotisserie chicken, consumers can figure on it being about 18%.

Raw Chickens and Rotisserie Chickens: Apples and Oranges?

Rotisserie chicken might not be a huge discount for the consumer, or a loss leader for the store, but it is a pretty good deal for takeout food. It’s certainly the winner if home cooks view their cooking time as money spent. When a cook’s time is included as labor costs in the above calculation, whole chickens become more expensive than rotisserie options.

As for the rotisserie chickens that sell for more than the raw chicken alternative, Super says, many consumers don’t mind the smaller size. For people who don’t cook, it’s often a plus. They want to finish off the chicken in one night, toss it out, and be done with it; they aren’t people who will turn the leftover meat into chicken salad with apple and pecans the next day.

In addition, many consumers prefer the preternaturally smooth, soft texture of chicken muscle that’s been injected with salt water, Super says. (Though foodies tend to detest it.) Whole chickens tend to befuddle people who are less than totally comfortable in the kitchen—how do you get it so the thigh joint isn’t red without cooking the breast to the point of sawdust?—and a rotisserie chicken, whatever its shortcomings, is better than they feel up to doing themselves.

For the most part, consumers are not getting the bargain with rotisserie chicken that they think. Mystery solved. But for people in a rush—or who don’t like to cook or hate leftovers—it’s the right item at the right price.

Our next article chronicles how Adolph Spreckels, America’s original “sugar daddy,” got away with murder. To get notified when we post it → join our email list.

This post was updated on August 15. The original article said that Costco offered the largest savings. The size of the savings offered by Costco and Smart & Final—in our experiment—are actually so similar that the difference between them is a rounding error.

![]()

Note: Priceonomics can help your company get better at creating content marketing that actually performs. Software, training and content creation services from Priceonomics. Starting at just $49 / month.