An Afghan money broker, or hawaladar, in Kabul. Source: NPR

It’s an alternative monetary system that operates largely outside government control, avoids large transaction fees by circumventing banks, and has associations with money laundering and the illegal drug trade.

No, it’s not Bitcoin, the digital currency beloved of libertarians and bankers, cypherpunks and Silicon Valley developers, and the buyers and sellers of illegal drugs on the Silk Road marketplace. It’s hawala, an informal money transfer system popular in the Middle East, North Africa, and South Asia that dates back to the Middle Ages.

Hawala is not a currency like Bitcoin. It’s a system that allows people to transfer money internationally via an informal network of money lenders and businessmen who rely on their reputation rather than formal contracts. By mirroring Bitcoin in sidestepping banks’ centralized control and overhead, and offering relative anonymity, hawala provides many of the advantages of Bitcoin (exchanging money for lower fees than credit cards or wire transfers) as well as the potential downsides people fear (illicit uses in money laundering, terrorist financing, and so on).

While its advocates believe that Bitcoin is a technological leap forward, in many ways its dynamics resemble a return to our hawala-like, pre-banking past.

Finance on a Diet

The promise of Bitcoin and appeal of the hawala system is attributable to a simple fact: the traditional finance sector is expensive.

Banks devote substantial resources to preventing fraud, mediating chargebacks, and complying with anti-money laundering and other regulations. Further, a market dominated by a few giants tends to charge markups and offer predatory services. As a result, banks charge fees of around 2.5% for every credit card transaction, which can easily account for half a business’s profit margins, while money transfer services charge comparable amounts and as much as 10% for international transfers.

Bitcoin and hawala can do better. As we’ll see, however, their ability to do better is linked to what opposing sides view as either a merit or a danger: their decentralized nature, relative anonymity, and utility to criminals.

Bitcoin and Byzantine Generals

Bitcoin and hawala avoid the overhead and fees of banks by not needing a trusted, central authority to mediate transactions. They simply do it in different ways, one modern, one ancient. Bitcoin uses open-source code to decentralize trust among a peer-to-peer network; hawala relies on the honor system and the power of personal reputation.

Although Bitcoin brings to mind an image of individuals sending digital coins between their computers and iPhones, it’s best to imagine Bitcoin as a single, public record of who owns which bitcoins. That ledger is constantly updated to reflect every transaction that has ever taken place, and it is maintained on all the nodes across the globe of the peer-to-peer network.

The challenge is to make sure that no one can fake the ledger to dupe everyone into believing that they control bitcoins that really belong to someone else. How do all the nodes in the network agree on the right record of Bitcoin transactions when inundated with fakes?

This is known in Systems Theory as “The Byzantine Generals Problem.” In a recent editorial, venture capitalist Marc Andreessen quotes the paper that coined the term:

“[Imagine] a group of generals of the Byzantine army camped with their troops around an enemy city. Communicating only by messenger, the generals must agree upon a common battle plan. However, one or more of them may be traitors who will try to confuse the others. The problem is to find an algorithm to ensure that the loyal generals will reach agreement.”

Bitcoin draws on a solution to this long unsolved problem. Priceonomics has covered the mechanism in depth in a primer on bitcoin, but it involves incentivizing individuals (with the promise of new bitcoins) to verify the public record. They verify the ledger by running a program that solves incredibly hard mathematical problems that require an expensive amount of computer power and electricity to solve — essentially by making random guesses until they find a match.

Since the mathematical problem contains the record of previous Bitcoin transactions, and its answer contains the newest public ledger of Bitcoin, the record of transactions is locked in. And since solving the problem is expensive in terms of computer power, it is inordinately expensive to fake.

When a mysterious figure named Satoshi Nakamoto published the code for Bitcoin in January 2009, it referenced a recent headline from The Times, “Chancellor on brink of second bailout for banks.” Nakamoto writes in a concept paper on Bitcoin:

The root problem with conventional currency is all the trust that’s required to make it work. The central bank must be trusted not to debase the currency, but the history of fiat currencies is full of breaches of that trust. Banks must be trusted to hold our money and transfer it electronically, but they lend it out in waves of credit bubbles with barely a fraction in reserve. We have to trust them with our privacy, trust them not to let identity thieves drain our accounts.

Since Bitcoin doesn’t rely on centralized powers like banks and governments, it’s favored by libertarians, crypto anarchists (in favor of a “cyber spatial realization of anarchism”), and banker bashers. Bitcoin uses cryptography so that users are pseudoanonymous, identified only by codes and keys, so proponents can imagine avoiding sales tax, cutting out banks, and depriving governments of control over the monetary system via Bitcoin.

But the capitalist class is equally excited about Bitcoin, and not just the Wall Street types who speculate on the rapid rise and fall of Bitcoin prices. Nakamoto finishes the above quote by adding, “[The banks] massive overhead costs make micropayments impossible.” Venture capitalist Marc Andreessen recently took to the New York Times to explain Bitcoin’s business potential.

By cutting out the high fees of banks, Bitcoin could benefit every business that regularly charges customers via credit card. That not only improves profit margins for companies across the board, but breathes life into companies whose margins would otherwise be too low to function. “I think lower costs will allow new industries and businesses to exist that could not otherwise due to high transaction fees,” Fred Ehrsam, co-founder of Bitcoin startup Coinbase told us in a previous interview.

Another benefit Andreessen mentions is that Bitcoin does not suffer from the headaches of international payments (high exchange rate fees, for example) that bedevil merchants trying to accept international payments. “If you are wondering why your favorite product or service isn’t available in your country,” he quotes fellow investor Chris Dixon, “the answer is often payments.”

Andreessen also imagines Bitcoin’s applications outside high-tech ventures. Low-income immigrants and migrant workers sending remittances to their families pay high fees. Using Bitcoin instead would allow families to receive more of their breadwinners’ savings, leading Andreessen to muse that “it’s hard to think of any one thing that would have a faster and more positive effect on so many people in the world’s poorest countries.”

He also imagines Bitcoin providing the “unbanked” — low-income individuals around the world, including 1 in 13 American households, who lack a bank account, often because they don’t meet minimum balance requirements or no banks serve their neighborhood — with access to digital payments and financial services. Doing so would reduce the high fees the unbanked pay on money orders, payroll checks, and other financial services that can amount to 10% of their income.

Hawala and the Honor System

The hawala system, which entails sending money abroad through small business owners who double as money lenders, has been around since before the Middle Ages. Despite its age, it has a number of parallels to Bitcoin. It can’t reduce the credit card fees that AirBnB pays or help digital services avoid foreign exchange problems. But it has been helping migrant workers and immigrants send money home and serving the unbanked for decades, even centuries.

In 2013, migrant workers and immigrants sent over $500 billion in remittances to family in their home country. For many countries, the influx of remittances constitutes a big chunk of GDP — up to 48% in Tajikistan, and $71 billion a year in India.

But the strivers sending money back home — migrant workers building Emirati skyscrapers, Mexican field workers on American guest worker visas — face a serious drain on their earnings. Banks and money transfer institutions like Western Union, on average, take 9 percent of the money that workers send home as the cost of doing business.

The hawala system is one of the informal channels used by migrant labor to avoid these fees.

Imagine an Egyptian construction worker named Ibrahim working in Dubai to send money back to his family. Ibrahim can go to a local hawala broker, or hawaladar, give him a week’s saved wages, and ask him to send it to his family in Alexandria, Egypt. The hawaladar will give Ibrahim a passcode, which he will also give to a hawaladar in Alexandria over the phone, email, or fax. Ibrahim will tell the passcode to his brother in Alexandria as well.

With the passcode, his brother can go to the Alexandrian hawaladar and receive Ibrahim’s week of saved wages. Unlike the 9% fee charged by formal services, the transfer costs less than5%, often 1% to 2%. (Some hawaldars offer the service for free.) But the hawaladar in Dubai still has the money. Rather than wire over the money, the hawaladars simply record that there is an outstanding debt between them.

The distinction resembles the difference between PayPal and applications that keep track of IOUs. On PayPal, users make immediate transfers between their accounts. Apps like Splitwise, in contrast, record every transaction as an IOU so that reciprocal IOUs cancel each other out and users can settle up every few weeks or months.

Most hawaladars take care of money transfers as a side part of their small business, so often hawaladars pay each other back in non-monetary ways. The most common case is by discounting goods in an export/import business. So in Ibrahim’s case, if the hawaladar he visits in Dubai exports goods to the hawaladar in Alexandria, the Dubai based lender can pay off his debt by discounting the value of his goods.

Hawala is referred to as an informal money system because there are no contracts. If Ibrahim’s brother never receives the money, he could not take the hawaladars to court. The only record of the transactions are the scribbled records of the hawaladars; they pay their debts and transfer money according to the honor system.

The honor system works thanks to a web of social and business connections that make a hawaladar’s reputation too valuable to risk by not honoring a debt. Breaking the honor system would diminish his social standing and hurt his business by ruining his professional reputation. It’s a formula that fueled money lending and long distance trade before central institutions existed to enforce contracts.

References to hawala date back to the 8th Century; its widespread use to the early Middle Ages. China’s similar system, known as fei-ch’ien (flying money), likely originated in response to the Tang Dynasty’s need to transfer tax revenues to the capital around 800 AD. A number of other regions have names for their own systems, all popular among merchants looking to avoid sending gold, jewels, and other currency over long, treacherous trade routes. Economist Avner Greif has chronicled how reputation based systems and collective action in Europe on a community scale — Merchant Guilds and community courts that forced merchants to honor debts for the sake of the local business community’s reputation — linked hawala-like systems to impersonal exchange and the modern economy.

Hawala has remained widely used despite the emergence of modern banking. Today, it mainly facilitates remittances and serves the unbanked. It’s hard to measure its size and prevalence. A cautious World Bank paper cites a rigorous study that found that hawala payments “account for up to 15 percent of small-scale trade between India and Bangladesh.” A less conservative academic paper cites a 2003 study finding that informal transfer systems like hawala account for $100-$300 billion in annual flows, an Interpol estimate from the same year that almost 40% of India’s GDP moves through the hawala system, and the Pakistani finance minister claiming in 2000 that only one sixth of Pakistani money transfers went through traditional banks.

The main advantage that has kept hawala relevant is cost. Like Bitcoin, hawala avoids the expensive overhead of banks. Further, hawaladar’s ability to profit off lending by arbitraging the difference between the official and black market exchange rate (in countries artificially trying to control the value of their currency) and other tactics allow them to charge low fees.

Bypassing all that bureaucracy allows hawala transfers to happen fast — sometimes within a few hours. It is also easier for illiterate and uneducated workers to use, and often more approachable as brokers tend to come from the same country or ethnicity as their customers.

Its versatility also makes it the sole option in places where banks don’t operate. Hawala brokers are the only financial system known to the “unbanked” in many rural areas, disaster zones, or conflict areas. Hawala persisted in Afghanistan during Taliban rule and in war ridden parts of Somalia. International organizations often use hawaladars to access money after natural disasters when banks are closed.

So while Andreessen hopes Bitcoin can improve remittances and help the unbanked, hawala has long been doing so for people from the Middle East, North Africa, and parts of South Asia and the Horn of Africa.

Hawala shares another feature with Bitcoin that makes it appealing to some users: relative anonymity. Just as the identifying feature in Bitcoin is an encryption key, hawala does not need names or real identities — just the passcodes shared between hawaladars, senders, and receivers. Brokers rarely bother verifying identities, choosing instead to simply use passcodes.

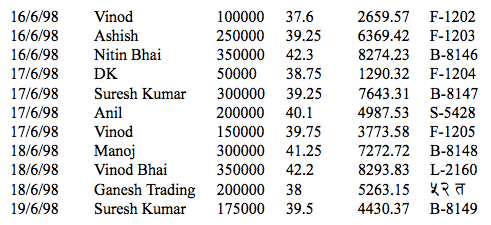

The transcribed bookkeeping of a hawaladar from an money-laundering investigation. The notes are often handwritten, frequently in a foreign language, and often using codes or shorthands. The name is the name of the other broker. The name of the sender and receiver are not included. Source: US Treasury Report.

Somali Pirates and the Dread Pirate Roberts

Bitcoin’s anonymity makes it popular with virtual pirates; hawala’s with actual pirates.

This past October, the FBI arrested Ross William Ulbricht and charged him with murder for hire and drug trafficking as the founder of the Silk Road, the “eBay for drugs,” under the alias Dread Pirate Roberts. The Silk Road facilitated the sale of tens of millions of dollars of illegal goods and services. By visiting the site via Tor and paying with Bitcoin, users could buy illegal drugs like marijuana and receive them in the mail.

A similar online narcotics store, The Farmers Market, previously existed. But the use of PayPal and Western Union allowed law enforcement to track down users, dooming the site. Bitcoin was key to Silk Road, and many early articles on Bitcoin described it as a currency for buying illegal drugs.

Silk Road clones have sprouted up, and concerns about Bitcoin’s illicit use extend beyond the site. Mt Gox, the most well known site for exchanging Bitcoin for national currency, had assets seized by the FBI due to such concerns and because it had not registered as providing money services in May 2013. More recently, a member of the Bitcoin Foundation board stepped down following charges that his Bitcoin business knowingly sold bitcoins to individuals selling them on Silk Road.

At the same time, Bitcoin has seen signs of acceptance. Prominent investors put money behind Bitcoin startups, the U.S. Treasury’s Financial Crimes Enforcement Network released guidelines on how Bitcoin could comply with financial regulations, and Ben Bernanke offered testimony containing equal parts caution about its illicit uses and the opinoin that “there are also areas in which [Bitcoin] may hold long-term promise, particularly if the innovations promote a faster, more secure and more efficient payment system.”

Hawala’s scare moment comes from 9/11, when the theory that the hijackers received anonymous, untraceable funding through a hawala broker gained popularity due to its Islamic roots. The 9/11 Commission report found “no evidence that the 9/11 conspirators employed hawala as a means to move the money that funded the operation.” And the hijackers were later found to have used a traditional wire transfer service. Nevertheless, in one analyst’s words, “hawala has remained in the eye of the storm for international financial regulation.”

The World Bank, U.S. Treasury, and other financial actors have multitudes of task forces and working groups considering hawala’s potential for financing terrorism, money-laundering, and funding criminal operations. And not without reason. Hawala is an avenue for the profits of the Afghan opium trade, Somali pirates’ ransom money, and may be used to bypass sanctions on Iran. It’s frequently used more mundanely to avoid taxes and launder smaller scale crime money. Still, most task forces concede the legitimate nature of most hawala transactions. In Somalia, for example, even the highest estimates of the pirates’ use of hawala would mean that the hijackers account for only 6% of money transferred out of the country.

The problem is that the merits and downsides of Bitcoin and hawala are a trade-off. The lack of a central authority overseeing the process is responsible for the positives of lower fees and speed as well as the downside of limits on government control over money flows. (Although plenty of people consider that a positive as well.) The legality of hawala, as well as regulations and enforcement, vary considerably around the world. Governments have only just started to address the question of Bitcoin regulations. The question is whether governments can create and enforce regulations they’re comfortable with — without destroying the merits of the monetary systems entirely.

Who says it’s “alternative?”

Hawala is often described as “informal,” “underground,” or “alternative.” Commentators often use the latter two to describe Bitcoin as well.

As several analysts note, the language suggests that hawala (or Bitcoin) is inferior or strange — and definitely in opposition to the norm of “traditional” banking. Treating Wells Fargo or Goldman Sachs as “traditional” is ironic, however, and the view of hawala as alternative is more of a matter of where you stand given that only about 20 countries have “fully modern banking and payment systems” and that hawala is the primary or only financial service used by hundreds of millions of individuals.

The expectation that hawala should follow the exact regulations designed for the impersonal bureaucracy of modern banks can be viewed as equally strange. Systems like hawala depend on trust and personal relationships. Indeed, some examples of friction between Western regulation and hawala amount to differences of opinion about what constitutes an illicit transaction, with many viewing its use to avoid a predatory governments’ taxes as a positive, and Afghans disagreeing with international opposition to the growing of poppy for opium. In criminal justice professor Nikos Passas’s words, “it makes no sense to apply the same measures to formal and informal financial practices.”

As Bitcoin is exchanged impersonally, it is not exactly analogous to hawala. But in many ways, it is just as strange to call it “alternative.” Bitcoin technology may offer new possibilities, but its merits and dangers also resemble those of ancient money systems like hawala. From a long view, modern banks like Wells Fargo are a strange new alternative, and Bitcoin is an algorithmic return to the past.

This post was written by Alex Mayyasi. Follow him on Twitter here or Google Plus. To get occasional notifications when we write blog posts, sign up for our email list.