Source: JCroft (Flickr)

A parade of half-naked hipsters dressed like Jesus, a six-foot tinfoil-fitted robot dancing to techno music, a grandfather hula-hooping in a leopard man-thong: these are the characters who inhabit Dolores Park. On any given sunny weekend in San Francisco, 10,000 people flock to the palm-laden park in the Mission.

In the last decade, Dolores has morphed into a minimally-regulated free space: vendors peddle goods, drug dealers conspicuously sling product, and Mission denizens fearlessly sip PBR tall boys in public. On the last Sunday of every month, the park embraces its free spirit attitude by hosting the Really Really Free Market, where “nothing is bought and nothing is sold.” People bring all kinds of free stuff — from highchairs to titanic-sized sweatpants that have seen better days — and take what they need.

How did Dolores Park evolve into the city’s reigning symbol of Laissez-faire transaction, and do vendors and citizens really enjoy unregulated privileges within the park’s confines? How do these vendors fare on a nice day?

Cemetery to Fixie Paradise: History of Dolores Park

Source: Dolores Park Works

Hipster Hill has a history even deeper than your v-neck. Inhabited by Ohlone indians for several centuries, the land was split when the Spanish arrived in 1776 and set up Mission San Francisco Dolores. Spanish ranchers and Ohlones shared the space rather peacefully until the Gold Rush in 1849. Settlers, gamblers, tavern keepers, and a hodgepodge of degenerates then set up camp and overtook the majority of the park’s current day land. In the same year, a city survey was conducted, revealing that only four parks existed within San Francisco: Portsmouth, Union, Washington, and Columbia.

In 1861, Congregation Sherith Israel purchased the space and used it as a Jewish cemetery; over 1,900 bodies were buried there before it became defunct in 1894. A 1939 article from the San Francisco Chronicle includes a resident’s recollection of what Dolores Park’s current-day land looked like after being neglected for a number of years:

“Time, weather and vandals assumed control, weeds choked the gravel paths, over-ran the graves. Tombstones fell. Ornaments, such as brooding angels became bedraggled — wings, arms, and legs missing.”

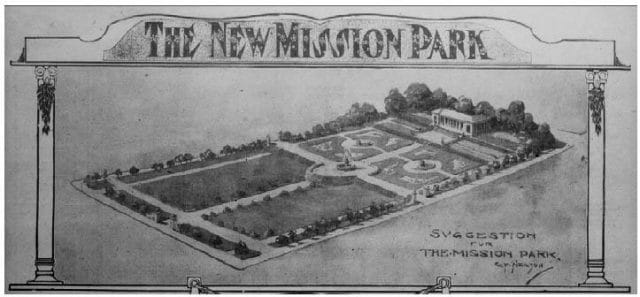

During the late 19th century, cemeteries were the only large-scale outdoor spaces in San Francisco, and served as parks; people would picnic, play catch, and generally spend the day carousing among tombstones. But following the development of Central Park in New York, the City of San Francisco began to reconsider its need for urban parks. Late 1897 saw the organization of the Mission Park Association, a group with the goal of securing a major park space in the Mission. In 1905, after years of lobbying, the association convinced the the City of San Francisco to purchase Congregation Sherith Israel’s land for $293,000 ($7.7MM in 2013 dollars), and declared the goal of creating “one of the most beautiful parks to adorn San Francisco.” The bodies were exhumed and moved to Colma, south of the city’s boundaries.

Barnum and Bailey Circus, the world’s most famous act at the time, agreed to dump hundreds of pounds of clay and sand to level a portion of the park’s land in exchange for use of the space for a few months to perform their new act. An article from the San Francisco Call in 1905 laid out plans for the new space:

“The park will contain a miniature lake 300 by 50 feet, so constructed that children can wade in it in warm weather. A magnificent stone stairway will lead down to the water from Church and Twentieth streets. On one end of the park a 12-lap cinder track will be laid, and inside the circle made by it will be erected an outdoor gymnasium. There will be two tennis courts in the grounds and two baseball grounds. A large bowling green will be laid out in the other section…The garden effect will be semi-tropical and the entire park stocked with broadleaf plants. A row of palms will border the entire square and an avenue of trees will be planted along the inner edges.”

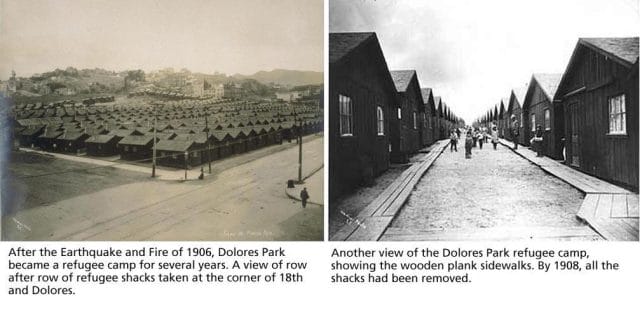

But in 1906, a magnitude 7.8 earthquake destroyed 80% of San Francisco, and a string of fires broke out that lasted nearly a week and killed over 3,000 people. Dolores Park was converted into a refugee camp, and remained one until 1908. According to a historic evaluation of the park, the camp included “512 three-room houses for 1,600 refugees” and cost the city $74,000; the displaced paid rent to stay there.

Source: Dolores Park Works

In 1908, construction on the park resumed with vigor. The city’s 1910 Annual Report described the progress that had been made just two years later:

“There are terraces, two tennis courts, a wading pool and an athletic field. Grassy borders, shade trees, groups of palms and flowering shrubs, render the grounds attractive. The expectations of the founders of the Park have been met.”

The reported cost for the tennis courts was $1,018; the pool was $127.50. In total, the report lists $1,820 in in total renovation costs for the park up to 1910.

Improvements continued through the 1920s and 1930s, but stagnated during the Great Depression and World War II, given the wartime shortage of materials and labor.In the years following the war, an influx of Latin American immigrants settled in the Mission and Dolores Park became a cultural hotspot for the community, but the landscape remained largely unchanged, save for a few additions: in 1966, a replica of the Mexican Liberty Bell was installed in the park; in 2009, a new playground was installed.

While the 1960s are often cited for the open use of drugs in Dolores park, it wasn’t until the 1990s that drug dealing became pandemic; with it, a free market sprung up in the park — and not just for drugs.

A Laissez-faire Zone for Vendors?

Source: Karl (Flickr)

Today, Dolores park seems to be a paradigm of free-market capitalism. Vendors roam openly beneath Mexican fan palms, selling goods to the needy masses. For weed smokers and PBR drinkers, Dolores is the Elysian Fields; police presence is sparse and the goods are plentiful. But since the inauguration of the park’s new playground, surrounding communities have lobbied for a more family-friendly park, and there has been more of a concerted effort to curb illegal distribution. While some vendors have continued business as usual, other have been cited and ceased.

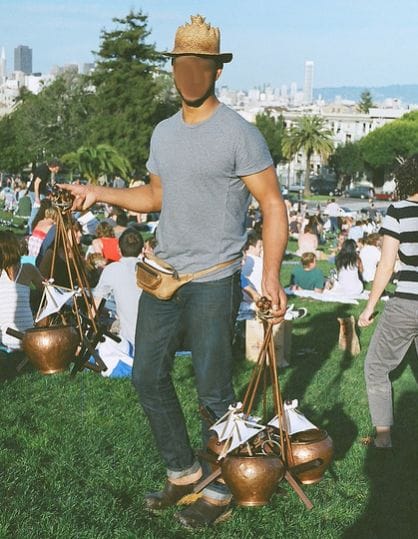

The “Truffle Guy” is among the lucky: he is unquestionably a Dolores Park staple. Toting a trademark straw hat, and an array of copper pots, he’s gained a cult following as a (supposed) weed chocolatier. His golf-ball-sized treats come in six flavors — coconut, espresso, cinnamon, ginger, pecan, and mocha — and you can buy three for $10 (or seven for $20); he says “one is usually enough for the average person.”

Also known as “Trevor,” he is itinerant, and has an unpredictable schedule; some weekends, he’s out in full force, and other weekends, he’s nowhere to be seen. But on the days he ventures out, he does well for himself. A source who claims to know Trevor well tells us the chocolate prince sells 120 truffles making his rounds on a good day, securing $400-500 in revenue.

His fan-produced Yelp page (that’s right, he actually has a Yelp page) boasts 64 reviews, and a 4.5 star average rating — higher (figuratively, and literally) than some Michelin rated restaurants. His business was hilariously placed on Google Maps, and he’s even been eternalized on a t-shirt. Online, buyers furiously debate whether or not his products are actually “enhanced.” One user claims, “half an hour in, I tripped so hard I ripped my pants; ” another contests, “total duds…where’s the beef?”

Source: Nicole Alexander Espina (Flickr)

The Truffle Guy has many competitors, including local gangs who sling in the park, and the “Ganja Treat Man.” “Have no fear, the real ganja man is here!” was a sales call commonly heard in Dolores until the Ganja Man was arrested and cited in 2012. Witnesses say they saw plainclothes cops stop the vendor, question him, and take him away in cuffs, his skull-embossed wizard cane in tow.

Tailing the Truffle Guy, and cashing in on weed-induced munchies, is the “Costco Pizza Man.” He merely buys four Costco pizzas for $9.95 a pop, and sells them for $4 per slice. Accounting for his $40 overhead, with ten slices per pizza, the Costco Pizza Man makes away with a quick $120 profit over an hour or two (his slices tend to sell quickly). Rumor has it that before he slung pizza, he sold beer out of paper bags; after being warned by police, he changed his business model.

Selling beer in Dolores is certainly not a novel idea. For years, a man named James, more lovingly known as “Cold Beer, Cold Water,” sold — you guessed it — cold beer, and cold water. Known for distributing PBR for a mark up (two cans for $5), CBCW often filled his small cooler with three 12-packs (purchased for $15 each at a corner store), and sold out within 20 minutes. He’d then return and repeat the cycle. Over a few hours, he would make $200-300, according to Uptown Almanac.

CBCW was arrested in 2012 during a crackdown, and was ordered to no longer sell beer. The police allowed him to continue selling water bottles, but his profits dwindled almost entirely.

Source: Mission Mission

“Hey Cookie!” is a goddess among baked-goods connoisseurs. Pigtailed, and wearing any of her 25 milkmaid-esque dresses, she circulates Dolores Park on the weekends, selling an amalgam of (non-laced) cookies. She says “some people are put off to be offered a non-medicinal treat in the park,” but she’s thrived. With a long list of treats — paleo coconut cups, gluten-free rich chocolate morsels, snickerdoodles, vegan mexican wedding cookies — she’s risen the ranks of Dolores street vendors. While she hesitates to discuss profit, she has accrued regular business outside of the park’s confines, often selling at local bars, and companies (Apple, Twitter, and Ubisoft included).

Another treat, paletas (Mexican ice cream bars), are plentiful in the park, but one man, “Hector,” says he has an edge over competing vendors: he’s been selling his coconut-flavored bars in Dolores Park since 1990. Over nearly twenty-five years, he’s learned the hot spots and has developed a natural intuition for seeking out high-demand environments. He doesn’t solely sell his pops in Dolores, but says that “on a good weather Saturday, it’s the best place to make money.”

When he first began, Hector purchased them wholesale from Delicias de Jalisco for $0.42 each, and he’d sell between 75 and 100 fruit bars a day, at $0.75 each, netting him about $30 on an average day. Things haven’t gotten much better over the years. Today, he gets his bars from La Michocana at $0.65 a piece, and turns each one over for $1.50; on a good day in Dolores, he sells 100 bars and brings in $68.

But popsicle sales are especially dependent on good weather and on mildly rainy, windy, or otherwise chilly days in the park, Hector’s sales drastically decline. When the weather is bad enough to keep hacky-sacking hipsters indoors, Hector doesn’t even bother selling for the day. It’s a tough life — the hours are brutally long, he’s on his feet all day, and his makeshift cart creaks and wobbles like a 90-year-old’s knee cap — but he persists, and chips away at making an honest living.

Source: Larry Beckerman

Conclusion

With Dolores Park slated for a $12.4 million renovation in 2014, we wonder how a half-closed park will affect foot traffic, the vendors who rely on extra weekend income, and the enforcement of park laws.

You’d never know it from experiencing a Saturday in Dolores Park, but there exists a tireless set of park rules and regulations in the San Francisco Municipal Code. Smoking is prohibited, public drinking is prohibited, and vending food and/or alcohol is strictly defined as illegal. Add to the mix city violations — drinking in public, peddling without a permit, marijuana possession (albeit the lowest priority of the SFPD) — and it’s a wonder that Dolores Park continues to function as it does.

Several crackdown efforts have been made. In 2012, 17 citations were handed out to vendors in just a two-month span; in 2013, the city imposed a curfew on hanging out in Dolores park, and closed it between the hours of 10 PM and 6 AM. But still, laws of any sort seem to be very sparsely enforced: hipsters continue to drink, stoners continue to blaze, and vendors continue to sell goods, largely without any hassle from the police.

So, is Dolores Park truly a free market economy? Not entirely — but it’s probably as close as you can get in San Francisco. The forces of supply and demand are minimally impacted by laws and regulations; goods are sold at freely set prices, adjusted based on desirability. The vendors are more often at the mercy of sunny skies and generous crowds than legislation and police. By most accounts, Dolores is a capitalist’s utopia, and both the vendors and their clientele intend to keep it that way.

This post was written by Zachary Crockett. Follow him on Twitter here, or Google Plus here.