In 2011, Sebastian Thrun co-taught an Artificial Intelligence course with Peter Norvig of Google at Stanford. They made it available for free online. Over 150,000 students from 190 countries signed up, along with the several hundred Stanford students on campus.

Impressed, he left Stanford to co-found Udacity and make courses available online in a massive scale. In his words:

“Having done this, I can’t teach at Stanford again.”

Another Stanford professor, Andrew Ng, had a similar experience teaching a Machine Learning course online. 104,000 people enrolled from around the globe. He co-founded Coursera, a similar organization to Udacity, noting:

”It would take me 250 years to teach this many people at Stanford.”

The courses available from Coursera and Udacity, along with edX and universities themselves, are called MOOCs: massive, open, online courses. They are free and open to anyone. If you enroll, there are assignments, tests, and even final exams that you will need to pass to complete the course.

MOOCs have exploded in popularity, but one criticism has been low rate at which people complete the courses. Sebastian Thrun has been quoted as being “deeply concerned by the 90% dropout rate,” while Daphne Koller of Coursera described a retention rate of 7% to 9% in their courses.

While their enrollment numbers are impressive, the concern is that MOOCs aren’t effectively educating people on the promised scale. As Thrun says, “MOOCS will only succeed if they make normally motivated students successful.”

But to what should these 10% completion rates be compared? The completion rate of traditional courses? To this authors’ knowledge, this data is not widely available. One standard is the federal government’s financial aid requirement that students complete 67% of the units they attempt. By that metric, MOOCs perform poorly. But the actual completion rate may fall below 67% in practice.

Besides, many people “enrolling” in MOOCs do so simply to get a sense of the course. The marginal cost of trying a MOOC is practically zero. It’s like piling a bunch of deserts on your plate at an all-you-can-eat buffet. Do you really expect to finish them all? This author, for example, once enrolled in 6 Coursera courses in a day just to choose one to take. Commentators note that a majority of enrollees likely sign up to watch the lectures and never intend to complete any course assignments.

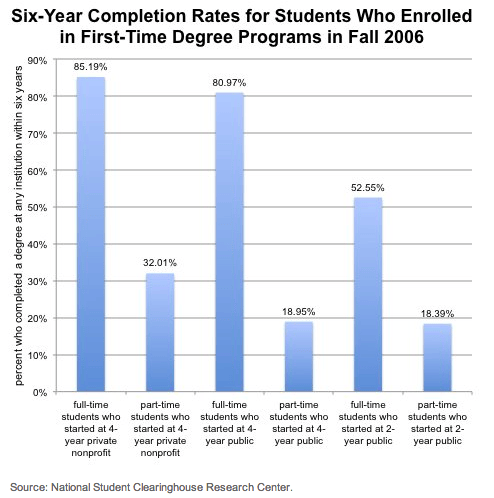

MOOCs are relatively new, so it’s not surprising that their impact is hard to judge. But one thing is for certain, the higher education industry that they’re targeting is ripe for disruption. Tuition costs are up, students hold over $1 trillion in student loans, and, as reported by The New York Times blog Economix, graduation rates from American universities are unimpressive.

Graph from The New York Times online

Public universities fail to graduate a fifth of their full-time students – an expensive failure. And very few part-time students graduate anywhere – a nod to the same problems MOOCs face of keeping students engaged in unstructured environments.

Critics may disparage MOOCs’ low completion rates, but integrating MOOCs’ reduced costs with the structure and guidance of a physical university may be the most promising way to improve higher education outcomes.

This post was written by Alex Mayyasi. Follow him on Twitter here or Google.