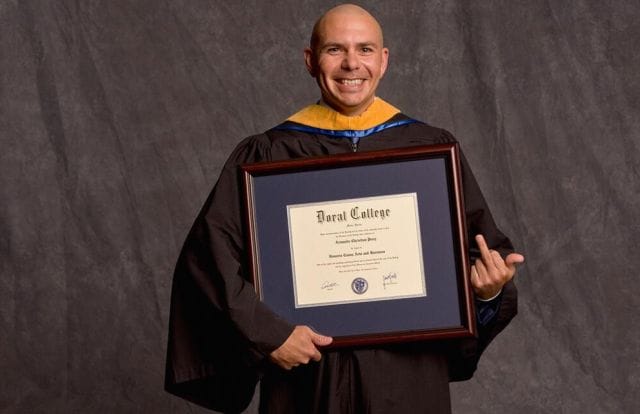

American rapper Pitbull shows off his honorary degree

![]()

Each Spring, thousands of American graduate students don fancy robes and walk across stages to accept their doctorate degrees. For most, the ceremony is the culmination of years of dedicated scholarship, hard work, emotional breakdowns, and tuition dues.

But for others present on commencement day, the struggle is not so real. Joining the students on stage, celebrities and business moguls — Mike Tyson, Kylie Minogue, Oprah, Ben Affleck, and Bill Gates among them — flock to college campuses to receive “honorary” doctorate degrees. Unlike the students, these luminaries are given a free pass: universities allow them to bypass all of the usual requirements. Though these degrees are more ornamental than functional, the practice of handing them out stems from a somewhat ignoble past.

For more than 500 years, the honorary degree has provided an opportunity for colleges to build relationships with the rich, famous, and well-connected, in hopes of securing financial donations and cheap publicity.

A Brief History of the Honorary Degree

Oxford University, where the “honorary degree” claims its origins

In 1478, representatives from England’s Oxford University approached a young bishop named Lionel Woodville. At the time, Woodville was a man of great honor: he was not only the head of the Cathedral Church of Saint Peter, but enjoyed the distinction of being King Edward IV’s brother-in-law. Well-connected, wealthy, and of noble standing, he was just the kind of man that Oxford wanted to curry favor with.

At the behest of the university, a finely-dressed courrier was sent to deliver Woodville a doctorate degree. For the nobleman, all of Oxford’s strict academic requirements were excused; with the presentation of a piece of paper, he was swiftly and automatically declared the modern-day equivalent of a Ph.D. This marked the first “honorary” degree in history.

“It was clearly an attempt to honor and obtain the favor of a man with great influence,” writes one historian — and for Oxford, the move paid off. Shortly after awarding him the degree, Woodville was offered (and accepted) a post as the Chancellor of the University. Throughout the 16th and 17th centuries, prestigious institutions like Oxford would don hundreds of other men, all of whom were members of the noble elite, similar degrees. In 1642 alone, some 350 doctorates were doled out by Charles I — many of which went directly to members of his court.

Meanwhile, in North America, Harvard University was in the midst of promoting Increase Mather, an influential Puritan minister, to President of the University. In 1692, just days before his appointment, Harvard instantaneously bestowed Mather with a ‘Doctor of Sacred Theology’ — a degree for which other candidates had to study a minimum of 5 years to obtain. This was the beginning of a long, steady procession of honorary doctorates at America’s most prestigious institutions.

Between 1700 and 1900, more than 200 different types of degrees were awarded, ranging from B.A., M.A., and Ph.D. titles (which came with all the benefits of earned degrees), to the LL.D., which was strictly ornamental and was not meant to insinuate academic prowess. Nonetheless, recipients of the latter often still considered themselves deserving of the title: Benjamin Franklin, who received honorary LL.D. degrees from 7 universities (including Harvard and Yale), was known to strut around town pronouncing himself “Doctor Franklin,” and often requested others refer to him in a similar manner.

Benjamin Franklin was among history’s early doctoral posers

Sooner or later, academics began to take issue with the honorary degree, and the haughty attitudes of those who’d been awarded them.

In 1889, Charles Foster Smith, a disgruntled man who’d actually earned his Ph.D., from Vanderbilt University, wrote a report bemoaning the practice of giving out honorary degrees. In it, he detailed that in a ten-year period alone, some 250 American universities had given out 3,728 degrees. He elaborates on his concerns:

“The mode in which honorary degrees are conferred in this country is a sham and a shame. It is so easy to get a degree — so many men of slight acquisitions have obtained a degree — that it is now the way to apply for these honors. If the secret sessions of college corporations were made public, there would be an astonishing revelation of intimations and open requests and endorsements. Members of the faculties of colleges are constantly applied to lend their influence to secure a doctorate for this person or that.”

Under the assumption that they were entitled to honorary degrees, hoards of “esteemed” men wrote letters to elite universities requesting to be decreed “doctors.” Many — particularly those who sent sizable donations with their letters — were successful.

Despite mounting criticism that the honorary degree made a complete and utter mockery of higher education, the practice only continued to grow in popularity throughout the 20th century.

“Degrees” Come Easy for the Wealthy and Famous

Today, honorary degrees are a big business.

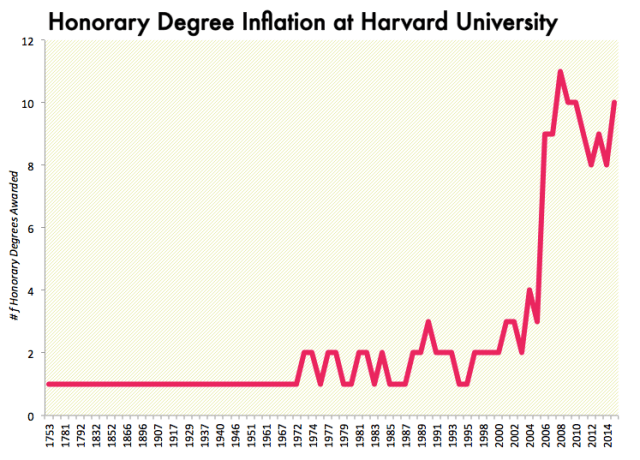

Over a period of three centuries, Yale University has awarded 2,805 of them. University of Pennsylvania has bestowed 1,722 — and as many as 56 in a single year. A representative in Brown University’s administrative office tells us they’ve given out somewhere around 2,030, averaging around 8 per year. But to truly understand to ballooning nature of honorary degrees, one needs look no further than Harvard University. Though the college only posts what it calls a “partial” list of its honorary degrees, the rate of increase there is in a league of its own:

Zachary Crockett, Priceonomics; data via Harvard University

Of the 171 honorary degrees Harvard lists on its website (going all the way back to 1752), 110 (a whopping 64%) were awarded in the past 15 years. Whereas the school traditionally granted 2 to 3 honorary diplomas per year, it now routinely awards 9 to 10.

Nearly all modern-day honorary degrees awarded by universities are one of the following: Litt.D. (Doctor of Letters), L.H.D (Doctor of Humane Letters), Sc.D. (Doctor of Science), D.D. (Doctor of Divinity), D.Mus (Doctor of Music), or, most, commonly, LL.D. (Doctor of Laws). For recipients of these degrees, matriculation, residence, study, and the passing of examinations are bypassed.

However, these specially-categorized degrees — which are technically classified as honoris causa, Latin for “for the sake of the honor” — are not “real” degrees, and as such, come with limitations. Most importantly, recipients are generally discouraged from referring to themselves as “doctor,” and awarding universities will often make this clear on their websites with some variation of the following phrase: “Honorary graduates may use the approved post-nominal letters. It is not customary, however, for recipients of an honorary doctorate to adopt the prefix ‘Dr.’”

As it turns out though, recipients of honorary degrees have been known to adopt the “Dr.” title that comes with “real” academic scholarship.

Author Maya Angelou, who was awarded over 50 honorary degrees from institutions around the world, often referred to herself as “Dr. Angelou” despite lacking a real doctorate degree. Similarly, software freedom activist Richard Stallman, recipient of 15 such degrees, routinely signs his emails “Dr. Richard Stallman,” and commands the same title when he gives talks, but holds no official Ph.D.

Combing through several Ivy League schools’ historical databases, it seems that honorary degrees are disproportionately awarded not to influential scientists, engineers, or historians, but to pop culture icons, big-name political figures, and wealthy businessmen.

It is not in the least bit unusual for these popular icons to be offered more than one honorary degree. Most U.S. Presidents have upwards of 10 apiece (George H.W. Bush has 32); Elizabeth Dole has 40. With 7 honorary degrees, J.K. Rowling has one for each of her “Harry Potter” books. Acclaimed actress Meryl Streep has more diplomas (4) than Oscars (3). Perhaps most impressively, Supreme Court member Ruth Bader Ginsburg has an honorary doctorate degree from every single Ivy League School, with the exception of Cornell, which doesn’t give them out.

Oftentimes, universities will offer these celebrities a degree in return for speaking at the commencement ceremony. Bill Cosby, of recent sexual allegation fame, has been awarded more than 100 honorary degrees — and in almost every case, he’s been expected to humor the audience. “The honorary doctorate — that’s lovely, he enjoys getting them,” his publicist told The New York Times in 1999, adding that Cosby actually does have a real Ph.D., ”but what’s important to him is getting the podium so he can can say something profound and funny to the students and their parents.”

But colleges’ incentive to offer degrees often goes far beyond securing speeches.

Why Do Modern Universities Give Out Honorary Degrees Anyway?

A little over a decade ago, Arthur E. Levine, president of Teachers College at Columbia University admitted that honorary degrees are about two things: money and publicity.

“Sometimes they are used to reward donors who have given money; sometimes they are used to draw celebrities to make the graduation special,” he told The New York Times. “I’ve always viewed it as a last lesson a college can teach, by showing examples of people who most represent the values the institution stands for.”

Last year, Burlington Free Press writer Tim Johnson compiled a list of every University of Vermont honorary degree recipient from 2002 to 2012, then dug into financial statements to see how much each of those individuals had contributed to the university in the decade preceding their “honor.” Here’s what he found:

“Of the 60 recipients, 35 were on the record as having made donations to the university, for a total of $13.6 million (an average of $228,248)…even excluding one degree recipient with an outsized $9 million contribution, the average was $68,854.”

His takeaway — that the university simply gave a degree to those who’d donated large sums of money — is no mystery. In another instance, after businessman J. Mack Robinson donated $10 million to Georgia State University’s School of Business, the school almost immediately rewarded him with a doctorate degree for his “outstanding contributions to the field of business.”

Aside from stroking the intellectual egos of wealthy donors, many universities see the honorary degree process as an opportunity to score some free publicity.

There is perhaps no greater example of this than when New York’s Southhampton College awarded an honorary doctorate in “amphibious letters” to Kermit the Frog in 1996. In the aftermath, 31 newspapers picked up the story, resulting in a “free marketing bonanza that raised the college’s profile and drew hundreds of new admissions.”

Kermit, receiving his honorary doctorate from Southhampton College; via Muppet Wiki

Amidst this controversy, some universities — notably Cornell, Stanford, and UCLA — choose not to participate. William Barton Rogers, the founder of MIT, regarded the practice of giving honorary degrees as “literary almsgiving…of spurious merit and noisy popularity.” To this day, the school does not award them.

Likewise, when Thomas Jefferson founded the University of Virginia, he explicitly banned honorary degrees, fearing that they would be awarded based on “political or religious enthusiasms rather than on scholarly considerations.” Today, instead of awarding honorary degrees, the University of Virginia presents the “Thomas Jefferson Foundation Medal,” an honor that is entirely separated from any associations with a doctorate degree.

Still, these institutions are a minority in the vast sea of colleges that continue the practice of doling out honorary degrees. And today, Jefferson’s fears seem to be as valid as they were 200 years ago.

Our next post takes a look at Cheeseboard, a pizza collective that is focused on creating a ‘truly democratic society.’ To get notified when we post it, join our email list. This post first appeared August 25, 2015.