This article was written by Alex Mayyasi, a Priceonomics staff writer

![]()

If you want to buy soap at the Walgreens on Market Street in San Francisco, you’ll need to find a store employee to unlock the display case for you.

Fifty dollar earbuds and $100 bottles of Claritin simply sit on the shelves where customers can pick them up and go. But baby formula, shampoo, and soap are all protected by locked display cases.

It’s well known that pharmacies need to protect their stores of cold medicine, which methamphetamine cooks can use to make illicit drugs. But why soap? Is a $6 bottle of Dove body wash really worth the squeeze?

A Walgreens keeps its precious Dove soap under lock and key

Managers at Walgreens have concluded that it is. If you go to a store and ask, retail assistants will explain that the locks prevent thefts.

Understanding why pharmacies lock up soap—rather than more expensive and appealing items—requires an appreciation of the market for stolen goods.

***

The key to understanding the appeal of soap to thieves is realizing that they care less about an item’s price tag and more about the ease of finding a buyer. In other words, thieves want a liquid asset.

This principle, along with the dynamics of thefts, are ably explained by an article in the Journal of Criminology based on a U.K. crime reduction study. It’s titled “How Prolific Thieves Sell Stolen Goods.”

The main markets for humble, shoplifted and stolen goods are in low-income, urban areas where people shop primarily at corner stores and street vendors. A British Crime Survey, the authors of the article explain, found that 11% of people interviewed said they had bought stolen goods in the last 5 years, and 30-40% of men in areas with “adverse area or personal wealth factors” bought what they believed to be stolen goods.

Knowingly or not, families in these areas purchase stolen or “fenced” goods often enough that thieves interviewed for the crime reduction study portrayed themselves as “one person among many providing an essential, albeit criminal, service in supplying the wants of a bargain seeking general public.”

These thieves sell their goods in one of 5 common ways:

1) Commercial Fence: Thieves sell stolen goods to a business owner (known as a “fence”) who sells it in his or her shop or to a distributor who sells it to shop owners

2) Residential fence: Thieves will sell stolen goods to a fence who buys and sells stolen goods out of his or her residence

3) Hawking: Thieves sell goods on street corners, in pubs, or door to door

4) Network sales: Thieves send word of their stolen goods along a network of friends and family until a buyer is found

5) Online: Thieves sell stolen goods on sites like E-Bay, or sell them to other fences who will sell them online

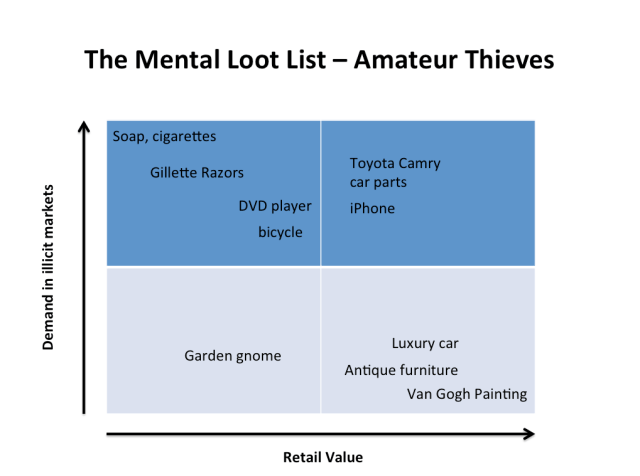

Thieves and burglars are very aware of the markets for stolen goods—and what sells in those markets. Most thieves have a “mental loot list,” the authors write, that they keep in mind as they approach stores or enter homes.

Thieves may even steal to order. One thief volunteered that when an acquaintance requested a “Mark V Escort, soft top, in cream,” he called him when he stumbled upon that exact car. Then he stole it and sold it to him.

Generally, though, thieves steal what is popular on the illicit market. The top of thieves’ mental loot list features expensive electronics like Playstations, GPS systems, and DVD players. Thieves can sell items for around a third of their retail value, according to the report, or for roughly half their value if they sell them to second hand shops. For expensive electronics, that means some solid, quick cash.

But price is not the only consideration. The “prolific thieves” interviewed by law enforcement suggest that the ease of selling something outweighs its retail value.

“If I come across something, the first thing I think of before I take it is can I sell it,” one former thief explained. “I mean I’m not going to take it if I can’t sell it, it’s no good to me. So when I’m taking that, I know exactly where it’s going.”

Not only do prolific thieves want the certainty of knowing exactly where they can sell their loot, but thieves want to get rid of it fast. One house burglar said that he took about an hour to sell stolen property. Most others said they sold off their loot in as little as 5 minutes.

The best way to ensure that loot is easy to sell is to steal products with consistently high demand. A hot electronic, like an iPhone, may fit the bill. But everyday consumer products are a less lucrative guarantee. In the U.K. report, one thief explained to the police that he focused on stealing cigarettes. Another man profited from the constant demand for popular razors:

“You could walk into pubs with a carrier bag full [of Mach3 razors] and all the blokes would take them off you. Everyone who shaves has a Mach3 razor. The [buyers] could get them off you without having to pay the full-whack.”

In fact, the consistent demand for products like soap on the illicit market can make it as good as stealing cash. Tide laundry detergent has widely been reported as a favorite target of drug gangs. In 2013, New York Magazine ran a story that described a Safeway store that lost $10,000 to $15,000 a month to thefts of Tide detergent.

Products like cigarettes and soap are appealing because they can perform some of the major functions of money. Since there is a consistent demand and market for them, even when they’re not on store shelves, they retain their value. (Unlike an iPod, they never become obsolete.) Since they have standard sizes, they can also be used as a unit of account. You can pay for a candy bar with a few cigarettes, or pay for an old phone with a few packs of cigarettes.

In areas where fences or other buyers are always willing to purchase stolen products, soap is just as good as money.

***

It seems logical for thieves to steal the most expensive items they can easily carry off.

But that’s only true before you think about the process of trying to turn stolen goods into money.

Consider how difficult it is to sell expensive jewelry. It’s hard to find customers, as few people are interested in buying jewelry at any given time. And even when customers are already in a jewelry store, they still need a lot of handholding from slick salespeople. Most thieves don’t want to hold onto stolen goods while they search out and win over a buyer.

In contrast, everyone needs soap all the time.

That’s why thieves care more about an item’s ubiquity in illicit markets than its retail price. In other words, they care more about stealing from the top two quadrants than they do about stealing items from the right-side of the below chart:

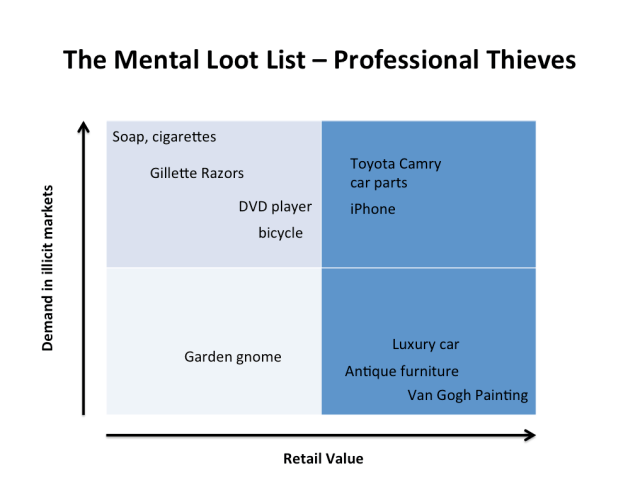

Only a sophisticated criminal organization—one that can place goods in warehouses and distribute more rare items to discerning customers—can prioritize retail value:

We can see this at work with the example of stolen cars.

Every year, the National Insurance Crime Bureau (NICB) publishes a report detailing the most commonly stolen cars. Invariably they are old, mundane cars. For the last several years, Honda Civics, Honda Accords, and Toyota Camrys sold in the early to mid 1990s topped the list.

As Frank Scafidi of the NICB explains, there are simply “gazillions” of these cars on the road, and their lack of newer, anti-theft technology makes them easier to steal.

But the real reason thieves target these old cars is for their lucrative parts. “Investigations often lead us to chop shops,” says Scafidi. “Those cars are stolen for parts.” Since so many people need their old Toyota Camry or Honda Accord fixed, there is a robust market for spare parts. And many chop shops will happily fence stolen parts.

Of course, expensive luxury cars are a favorite target as well. A different database from the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration lists the cars with the most insurance claims per 1,000 vehicles on the road. It doesn’t distinguish between the theft of items within a vehicle versus the car itself. But it’s telling that the cars that top the list are luxury cars like the $92,000 Audi S8 and BMW’s M5 sedan.

It seems that most thieves steal old sedans to quickly sell their parts, while the Gone in 60 Seconds wannabes steal luxury cars.

***

Even though it’s counterintuitive, there’s a simple reason for why stores can be more protective of cheap products than expensive ones.

As a Walgreens cashier explains, “It’s easy to sell on the street. Everyone uses soap.”

Our next post explores a glorious period of America’s past, when lobbying was illegal. To get notified when we post it → join our email list.

An earlier version of this story was published on March 21, 2014.

![]()

If you’re a company that wants to work with Priceonomics to turn your data into great stories, learn more about the Priceonomics Data Studio.