The World Bank publishes hundreds of reports every year — from “Why Don’t Remittances Appear to Affect Growth?” to its annual World Development Reports. This month, the bank discovered that no one seemed to be reading them. It published its results in a report, which, ironically, went viral. As one Redditor summed it up: “Nearly one-third of World Bank reports have never been downloaded, not even once.”

The World Bank, an international organization that provides loans to developing countries, considers informing public debate a part of its mission. So in a laudable act of self-accountability, it published a report in early May looking at how often people downloaded its reports or cited them in other research.

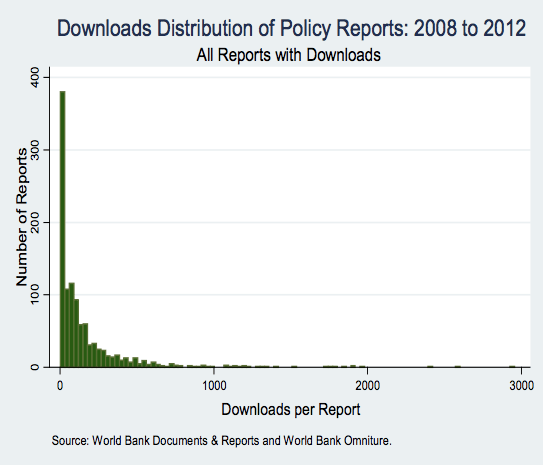

The results, shown in the above chart from the World Bank, aren’t pretty. Over 30% of the 1,611 policy reports published from 2008 to 2012 were never downloaded. As each report costs an average of $180,000 in terms of researchers’ time and other expenses, a ballpark estimate of the amount of money spent researching and writing reports that did not merit a single download is $93 million. In addition, 87% of the reports went uncited.

Some disclaimers are in order: Someone did read these reports, often attendees of conferences given paper copies or stakeholders emailed a copy of the report. And as the researchers note, many of the policy reports “were not intended to reach a large audience but prepared to assess very specific technical questions or inform the design of lending operations.”

In fact, the World Bank may be doing fairly well at staying relevant to public debate. A separate study cited by the Bank found that almost 70% of World Bank titles (a broader category than policy reports) garnered media coverage within 3 years of publication. Yet another finds that despite the large body of uncited work, the World Bank is on par with prestigious economics departments in terms of scholarly citations. The distribution of a large number of little read reports but a few highly read reports is a familiar one in online media, where a few articles or videos that are “hits” account for the majority of traffic to sites like The Atlantic, Buzzfeed, and Priceonomics.

The World Bank’s report on how often people download and cite its reports — Which World Bank Reports Are Widely Read? — is available as a PDF on its website. It is now one of those rare World Bank reports that gets a lot of attention, as its findings made the rounds of the social web in blog posts and on sites like Reddit.

We suspect that one reason for its popularity is that almost everyone can relate to the experience of writing a report or memo and wondering if it will ever be read… or lost in a Kafka-esque hell of bureaucracy. It also fits nicely with everyone’s favorite government bashing storyline — even if the World Bank is an international organization — of employees writing frivolous reports. (Even though the bank’s report describes its media and dissemination strategy and efforts to increase buy-in from the countries the reports intend to analyze and aid.)

But the lesson we all should probably be learning from the World Bank’s overly honest look at itself is that PDFs are terrible.

Each of the policy reports analyzed by the bank is available on the World Bank website as a PDF or “portable document format.” Probably the easiest way to understand why one third of World Bank reports are never downloaded is to think about how many times you received an email with a PDF attachment and simply couldn’t be bothered to download and read the document.

Complaints against PDFs are legion. They take time to download and require a plug-in. They are hard to navigate, as you can’t link people between sections, which also means they can become unmanageably large. (Since a 5,000 page report cannot be broken up into parts.) It is difficult to copy and paste from a PDF. And, as one commentator adds, “that little disembodied hand [used to scroll in PDFs] is just freaky.”

Most importantly, they simply suck for the web. PDFs take extra time (and clicks) to access, they are difficult to share, and they can’t easily link to other online material. Although it’s possible to optimize PDFs for search engines, the posters rarely do and any reader who is not an invested researcher will hesitate to click on a PDF in Google search results. You also can’t navigate easily from a PDF to other parts of a website. Even the ultimate listicle of dog and cat pictures would be read by no one if Buzzfeed posted it as a PDF.

Despite the disadvantages, laziness keeps PDFs alive on the web. A simple conversion can turn any Word document into a PDF, which then can be placed online. As one consultancy writes, “Websites use PDF despite its weaknesses because it supports ease of posting, even as it denies ease of use.”

PDFs have some uses, such as printing. But otherwise, please free your prized reports from their PDF prisons.

This post was written by Alex Mayyasi. Follow him on Twitter here or Google Plus. To get occasional notifications when we write blog posts, sign up for our email list.