Arguing is futile – people very rarely change their mind in response to debates or policy papers. But when it comes to making snap judgments about new information, or judging what Stephen Colbert would refer to as the “truthiness” of a statement, suddenly people’s minds go from brick walls to porous sieves. Our brains did not evolve for philosophy seminars, they evolved to make decisions based on limited information. And that fact can be manipulated. Here are three ways to do so:

1) Use words like “because”

A statement will be more convincing when a reason is given to back it up. But as the work of Harvard psychologist Ellen Langer has shown, so too will a statement backed up by the semblance of a supporting reason.

In a series of famous experiments, Langer had her research team ask people standing in line for a photocopier if they could skip the line. One group told people, “Excuse me, I have five pages. May I use the Xerox machine?” Despite having a good reason to skip the line (only having a few pages), only 60% of people said yes. In contrast, 94% of people acquiesced when the word “because” introduced a reason for needing to skip the line: “Excuse me, I have 5 pages. May I use the Xerox machine because I’m in a rush?”

It seems the word “because” reminded people that the request was informed by a good reason. But the word was just as effective when no real reason was given. Ninety three percent of people complied when the research team asked, “Excuse me, I have five pages. May I use the Xerox machine because I have to make some copies?”

The lesson: use the language of good reasoning and solid argument even in their absence. Words like “because,” “moreover,” and lists of evidence or “five point plans” all have the feel of good logic.

2) Tell a story

Imagine that you are a juror in 2 murder cases. In one, the prosecutor lays out evidence suggesting 70% odds that the defendant was at the crime scene, but can’t supply a motive. The second case is identical, except that the prosecutor describes the middle-aged defendant’s history as a bully in his early teenage years. Which is more convincing?

Although some childhood bullying is unlikely to explain a homicide committed decades later, the second is likely much more convincing. As research from psychologists Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky has shown, people respond strongly to irrelevant evidence if it matches their expectations. They had participants rate the odds of someone being a doctor or lawyer. They told them the composition of the group the individual came from (for example, 70 doctors and 30 lawyers), so they knew the odds. But when provided with a character sketch of an individual, the psychologists found that participants ignored the known information about the actual numbers of doctors and lawyers and instead based their judgment almost entirely on the degree to which the character sketch matched stereotypes of the occupation.

We tend to fit ideas and facts into stories. Better stories are more convincing. So although not all criminals were bullies and not all engineers are nerdy, we give too much credence to what matches our expectations. The fact that juries can find well told stories too convincing is recognized in legal debate.

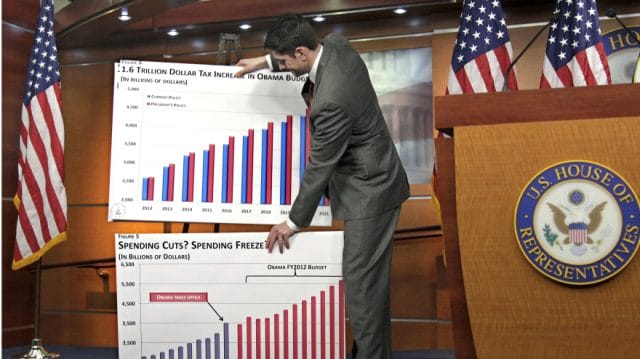

3) Point to pictures or graphs

In a recent study, psychologists had participants rate whether they thought a number of factual statements – from whether a celebrity was alive or dead to whether “macadamia nuts are in the same evolutionary family as peaches” – were true or false. As Scientific American reports, the presence of a picture or short description increased the number of people who believed that the statement was true – even when the picture or blurb provided no relevant information. Although the psychologists wouldn’t stake a definitive position on why, it seems that information surrounded by pictures or additional details just seem more convincing.

We make no claim that Paul Ryan was lying during his many presentations on the national debt in the run up to presidential elections (see above picture). But we do recommend caution whenever someone shows up with enough charts to beat you into submission.

This post was written by Alex Mayyasi. Follow him on Twitter here or Google Plus. To get occasional notifications when we write blog posts, sign up for our email list.