When the Georgia Aquarium broke ground in 2005, UPS made a generous donation: at no cost, they offered their logistics and shipping services for whatever the facility needed. It didn’t take long before their corporate headquarters got a call from Atlanta.

“This is going to sound strange, but hear me out,” said the voice on the line: “we’d like to transport some really, really big fish.”

The request — to haul four whale sharks in Taipei and two beluga whales in Mexico to Atlanta — was daunting, but UPS had just the man for the job. As one of the company’s cargo load masters, Bland Matthews has made a career out of shipping seemingly impossible items. In his 20 years at UPS, he’s played an instrumental role in moving everything from 2,000-pound whales to China’s Terracotta soldiers. Dream up an item, however delicate or colossal, and Mathews will swiftly sculpt a plan of action: he’s a logistical guru.

So, how does a man ship whales? To start, he never says “no.”

Say ‘Yes’ and Figure It Out Later

Contrary to his first name, Bland Matthews is anything but dull.

Born in the Kentucky countryside to a CIA agent father and Danish-American mother, he spent his early days debating geopolitical events at the dinner table. “Most of my friends didn’t think outside of the county line,” he says. “I was fascinated by the Cold War; when the Soviets invaded Afghanistan in 1980, I was thinking about how to defend the Khyber Pass.”

In his teens, he briefly entertained the idea of being an aeronautical engineer, but soon resolved that he wasn’t much interested in math; instead, he worked two jobs to pay his way through a political science degree at the University of Louisville. By 1995, a few years out into the real world, he settled on something uncanny.

“There was a place down in Louisville I’d never paid much attention to called UPS [United Parcel Service],” says Matthews. “They gave you great insurance. That sold me.”

About a decade earlier, UPS had founded its airline division, and established the Louisville International Airport as its hub. To ship 15 million packages a day across the globe, the company utilized its fleet of 237 cargo planes (mostly large Boeings), and a workforce of 20,000 employees — including the young Matthews. For his first job, he was tasked with parking airplanes.

“I was the guy with the wands,” he clarifies. “Rain or shine, I was out there.”

Matthews wasn’t content for long. A year in, he gave UPS an ultimatum — “give me a better job, or I’m gone in two weeks” — and was swiftly promoted to part-time supervisor, and tasked with overseeing the loading and unloading of cargo aircraft. A few years later, when UPS began experimenting more with passenger charter flights, he was put in charge of “conversion operations,” which required him to seamlessly convert cargo planes to passenger planes on weekends, and, among other things, escort Lenny Kravitz to the Bahamas for birthday parties.

A cleared-out Boeing 767 ready for cargo

In September of 2001, UPS Airlines closed down its charter division and Matthews found himself in a precarious position. Just before Christmas, his manager sat him down for a chat. “If you don’t have a job by January 1st,” he was told, “we’re going to let you go.”

On Christmas morning, he received a call. “They asked me to be a ‘cargo load master’ and I immediately said yes, not even knowing what that was,” says Matthews. “When a door opens, I don’t say ‘I can’t do it,’ — I just say yes, then figure it out later.”

To some extent, Matthews didn’t really know what he was in for.

As a member of the Civil Reserve Air Fleet, UPS had volunteered its planes for use by the U.S. military in the event of war. Post-9/11, that offer was accepted with open arms. Within his first few months as cargo load master, Matthews found himself flying out charters and supplies to the Middle East — Turkey, Kuwait, Pakistan — often unsupported.

“I’d get flown out somewhere with no other local UPS support, and I’d work with people I never met to get a job done,” he says. “But I’m comfortable in situations where there is no playbook.”

Four years later, he proved just that.

Whales in Flight

Beluga whales at the Georgia Aquarium

Funded by a $250 million donation from Home Depot co-founder Bernard Marcus, the Georgia Aquarium was launched in 2005, with the grand vision of being the world’s largest marine exhibit. Four recently-acquired animals — two whale sharks, and two beluga whales — would be the coming attraction.

But there was just one issue: these majestic creatures were located thousands of miles away, in Taipei and Mexico City.

Back home, Matthews had become known as one of UPS’s “solution guys.” Every time there was a shipment that was logistically unprecedented, he’d be there to help come up with a plan — and when UPS received a request from the Georgia Aquarium to transport two whale sharks from Taipei, he was enlisted as the point man. There was no prescribed plan for going about this: it would mark the first time in history that whale sharks were transported by air.

Matthews’ initial order of business was to assemble a skilled team of veterinarians, carpenters, and subject matter experts. Then, after three months of rigorous planning, he embarked to Taiwan.

The four whale sharks, which had recently been caught in the sea, were still in an ocean pen. Originally, the plan was to fly a specially-equipped Boeing 747 into a tiny airport right along the water, and load them in with a system of pulleys, but when they surveyed the area, they realized the 300,000-pound jet would be so heavy once the whale sharks were inside, that the weight would leave divots in the concrete. Instead, the team loaded the fish into a smaller Lockheed c-130 at the beach, flew them to Taiwan Taoyuan International Airport, then “rolled them out” into the 747 for the flight back to the United States.

An aquarium specialist secures a whale shark off the coast of Taipei, Taiwan

The whale sharks are loaded into their custom tanks

Each 16 feet long and weighing 2,000 pounds, the fish required two custom-built 8-by-24-foot tanks. With water weight, the load exceeded 50,000 pounds. A 747 can carry up to 120,000 pounds, so the weight wasn’t the issue; the issue, says Matthews, was where to put them, and how to distribute the weight. If he put it all on the nose, the nose wouldn’t lift, and if he put it too far back, the plane would pop a wheelie.

Matthews’ solution, though rooted in numerous calculations, was simple:

“I used the first fish to counterbalance the second fish. When I brought the first one in, I ran her all the way to the nose of the plane, to the cockpit. Then, once I got the second animal into the very back of the plane, I simultaneously moved both animals toward the sweet spot.”

That “sweet spot” — or the natural point of balance for an airplane — tends to be right over its main gear:

Once he had the animals situated properly, it was a race against the clock. “The process to move an animal is all about timing,” he says. “You can’t have a delay when you’re moving animals. They’re constantly pooping and pissing, and fouling the water, so you’ve got to get them out as soon as possible.”

The 17-hour, 8,000 mile journey back to the Georgia Aquarium required a stopover in Anchorage, Alaska for a Fish and Wildlife inspection — because, of course, “you can’t just go fly fish across the world without the proper permits.” Back in the air, the sharks “flew like a dream,” and made it to Atlanta healthy and safe.

* * *

Matthews was only half-way done: he still had to transport the two beluga whales from Mexico City — a task that ended up being more logistically challenging than the first. Though he’d been warned by the aquarium that the whales were “distressed, and in subpar conditions,” he wasn’t prepared for what he found.

“The tank was literally in the center of a roller coaster, in the middle of an amusement park,” he says. “They were put in the tanks when they were 6 feet long, and at the time of transfer, they were 15 feet long. I thought, how the hell am I getting these [whales] out of this park?”

An unorthodox situation required an unorthodox solution:

“I noticed there was a children’s train that went through the park. So, we built a rail car to connect to this train. Then, we built a crane, lifted the whales out of the water, put them in the rail car, drove the train to where these tracks went right next to the park’s outer fence, picked them up with another crane, and put them into a flatbed truck bound for the airport. In one move, we had trains, planes, and automobiles.”

Beluga whales can grow up to 15 feet long, and weigh up to 3,500 pounds; they don’t particularly like being air mailed

The plan required everything to be carefully placed and orchestrated beforehand; one little mistake could’ve cost the animal’s life. Expert veterinarians and translators were on hand, and the police were enlisted to clear out the highway and Mexico City International Airport. No resources were spared.

In the end, the beluga whales made a secure flight back to Atlanta, where they joined the whale sharks.

Though UPS transport was a donation, a shipment like this would’ve hypothetically come with a massive price tag. “Just to start the 747 costs $20,000,” says Matthews. “The flight cost alone to get the whale sharks from Taipei to Atlanta was something like $340,000.” Taking into account the massive teams of experts that need to be involved, the bill for these projects can easily run into the millions.

But often, adds Matthews, it was the charitable shipments that were the most rewarding.

Overnight Hospital Delivery

Hundreds of Hurricane Katrina victims flock to a field shelter; via FEMA

At 4 o’clock in the morning on August 29, 2005, UPS received another call — this time from FEMA. Hurricane Katrina had caused New Orleans’ levees to break, and they needed help transporting an army hospital from Reno, Nevada to NOLA.

“With the whale sharks, we’d planned for three months,” says Matthews. “This time, we had to go immediately, with zero plan.”

Matthews faced the insurmountable task of hauling hundreds of beds, blankets, medical supplies, and machines across the country, and all he was given to start with was the name of a master sergeant in the Reno National Guard. He found a quiet space, gathered his peace of mind, and scribbled a plan down on the back of a napkin in ten minutes. Then it was “go” time.

After gathering what he guessed would be the necessary pallets, nets, and straps, he flew a crew out to Reno, found the sergeant, and did the weight and balance equations for the equipment in his head as it was being loaded. He weighed each pallet, loaded them onto the plane in what he thought were the right positions, then flew off.

“The scene in New Orleans was Beirut, 1980,” he says: “army helicopters, smoke coming out everywhere, no power, no fuel..it was wild.”

With no power at the airport, and no visible taxi lanes for the aircraft, an interim rule was established: if a plane didn’t leave before the sun went down, it had to spend the night. Matthews was highly motivated to leave, but he was stuck in an unloading line with nine jets ahead of him. In an act of true desperation, the UPS faithful detoured out of line, blocked in at competitor’s loading area, and used his enemy’s equipment to unload the hospital.

“With two people, we unloaded the entire thing in 30 minutes,” he says. “Then, we got the heck out of dodge.”

How a Man Moved an Army

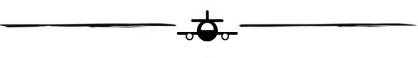

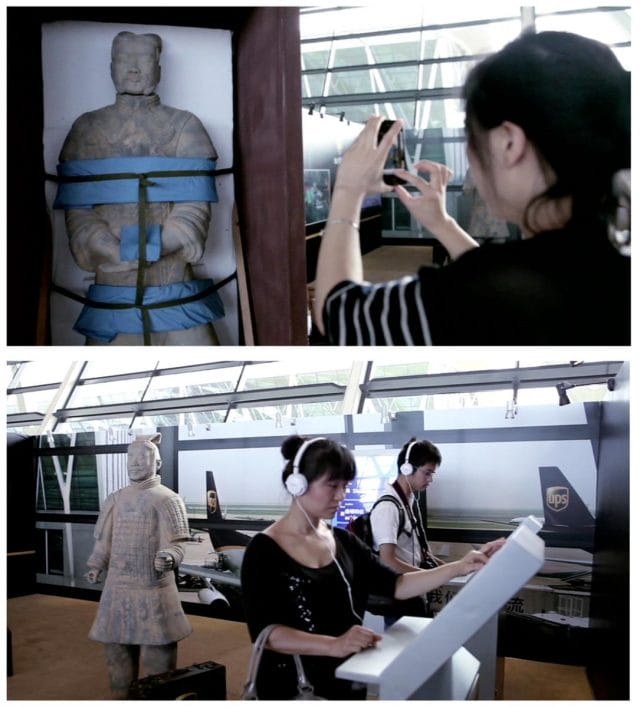

China’s beloved Terracotta Army soldiers, all packed up and ready for transport

Unearthed in 1974 by a group of local well-diggers in Xi’an, China, the Terracotta Army is a collection of sculptures — 8,000 soldiers, 670 horses, and 130 chariots — all life-sized, that were buried with Qin Shi Huang, the first Emperor of China, in 210 BCE. More than 2,000 years old, they are delicate, irreplaceable artifacts with tremendous cultural value.

In 2009, Matthews faced one of his biggest challenges yet: assisting UPS in taking 15 of these soldiers on a 66,000 mile tour across the world.

Packed in 42 specialized crates designed to minimize vibration, and stored in a climate-controlled, 70-degree F cabin, the Warriors proceeded on an epic journey. After two flights — one from Shanghai to Anchorage, and another from Anchorage to California — they were loaded onto UPS Freight trucks, and carted to their first destination: the Bowers Museum in Santa Ana. From there, they went cross-country, making stops in Houston and Atlanta, before parking in Washington D.C.’s National Geographic Museum. Along the way, the police shut down highways, and trailed in helicopters and unmarked cars to keep things covert.

In total, a team of 120 specialists collaborated with Matthews on the move.

“I knew nothing about trucking, or how to safely protect antiquities, but I was able to find the right people and bring all their skills together to find a solution,” he says. “When you move something that’s 3,000 years old and irreplaceable, you get to a pretty intricate level of selecting who to work with.”

The UPS Guy

Bland Matthews’ craziest days at UPS are behind him.

Married with two kids, he’s since settled into a more stationary role as the company’s international postal manager. Now, like most UPS employees, he’s simply “in the business of moving mail.” But Matthews’ logistical talents are still put to use.

“I’m not doing much loading anymore,” he says, “but I’m still using my skills and imagination to come up with interesting solutions to things.”

When Hurricane Sandy hit New York in 2012, to U.S. Postal Service — one of UPS’s biggest customers — lost a massive fleet of trucks and needed assistance. Like a parcel-gilded angel, Matthews came to the rescue: for a month, nearly all of the mail east of the Mississippi River was handled by UPS. In February 2014, UPS started delivering mail to Afghanistan, and Matthews once again found himself occupied with the Khyber Pass, calling into action armored trucks, and navigating his way through airport explosions.

“Rarely do you discuss explosions at UPS meetings,” he jokes, “but when you’re dealing with Baghdad or Kabul, that’s par for the course.”

But really, these types of things are just par for the course for the man’s career. Whether it’s finagling a beluga whale out of a roller coaster or moving mail into a war zone, Matthews has written the playbook for situations where none previously existed.

“I may’ve had no idea where the hell to start on a project,” says Matthews, “but I was willing to take a risk to start somewhere.”

This post was written by Zachary Crockett. You can follow him on Twitter here.

To get occasional notifications when we write blog posts, please sign up for our email list.