To pretty much everyone’s amusement this week, Tim Draper’s initiative to split California into six smaller states fizzled. In his attempt to get it on the ballot, the prominent venture capitalist had invested nearly $5 million of his own funds.

In California, there exists a bizarre rule: If you gather enough signatures, you can get essentially any initiative on a ballot for the general public to vote on. Want soda in the water fountains? Sure, that can be on the ballot — just get over 807,615 signatures. Lower taxes? More government services? Lower taxes and more services? Puppies? A ban on puppies? With a certain number of signatures, the ballot will feature anything your heart desires.

In practice, people like Tim Draper and his supporters aren’t going around and gathering signatures among die-hard supporters of their causes. Instead, they pay political petition firms boatloads of cash to get names inked on paper. These political consulting firms have one job: To get a customer’s “pet” initiative on the ballot through the acquisition of signatures.

And in this case, the firm hired by Tim Draper, Arno Political Consultants, made a serious miscalculation: They didn’t get enough signatures. Upon submittal of signatures, the California Secretary of State’s office will check a sample to ensure names and addresses match up with voting registration records (this is to verify that signatures are inscribed by valid voters and aren’t falsified). Typically, to ensure a buffer, firms need to collect a bit more than the number of votes they anticipate needing.

While Arno claimed to have collected 1.3 million signatures, only 752,685 ended up being valid. That’s 7% fewer than the required threshold of 807,615 signatures! As a result, “Six Californias” will not be on the upcoming ballot, and $5 million of Tim Draper’s money was completely wasted. Whoops. Barring a last minute reversal, he’ll have to start the process all over again if he wishes to continue his campaign next year.

But we’re curious: How does a firm collect a whopping 1.3 million signatures for a complex plan to atomize California in the first place? Let’s dig in.

Plutocracy 101: How to Get Your Initiative on the Ballot in California

To get your very own Constitutional Amendment on the ballot in California, you need to get around 808K signatures from voters saying they want this measure on the ballot. Getting that many people to physically sign a paper is a pretty tough problem. Luckily, there are a handful of companies that specialize in solving that problem — including Arno Political Consultants, the company that Tim Draper used.

Basically, you pay a firm a fixed dollar amount per signature and they go out and get the signatures within a 90-day required time period. According to Ballotpedia, a non-partisan political encyclopedia, the typical going rate is around $2-3 per valid signature, though sometimes the price can reach almost $10 per signature.

The firm will then work with an army of freelancers who are responsible for collecting the signatures. As freelancers get paid per signature, they have an incentive to get as many as possible.

There is, however, a “hack” in this system: A freelancer will have a whole stack of different ballot propositions he is working on. So if he finds one person willing to sign a ballot initiative, he can persuade them to sign a whole bunch of petitions at once. Hypothesizing a stack of five different initiatives at $2 a signature, one compliant signee can net a freelancer $10. A freelancer hanging out in grocery store parking lot all day can make some serious money this way.

A Case of Bad Incentives

The fact that a freelancer’s salary is dependent on the number of signatures he accrues creates some questionable incentives that are reminiscent of the last housing crisis. Mortgage brokers, like these freelancers, made a commission on every mortgage they wrote. Just as this led to some bad mortgages being written without proper oversight, it also leads to some bad signatures being collected by political consulting firms.

There are two ways a signature-collector can abuse this system for his profit. First, he can simply forge signatures. Since consulting firms often perform spot checks on sample selections of signatures, this isn’t necessarily a good strategy and can jeopardize getting hired in the future.

Secondly, a signature-collector can abuse the system by distorting the truth about the ballot measure’s intentions when trying to get signatures. Say you’re a freelancer trying to get signatures for initiative on the ballot that blocks new construction of apartments in San Francisco. You’d probably say to people walking by, “Hey, sign this petition if you want to help save the waterfront!” instead of something more honest (but less sexy) about new housing being curbed.

Can you imagine being a signature-gatherer tasked with explaining an initiative to split California into six micro-states? It would take you 20 minutes just to explain the damn idea. And what are the odds that someone would sit through this and actually sign the petition? Miniscule.

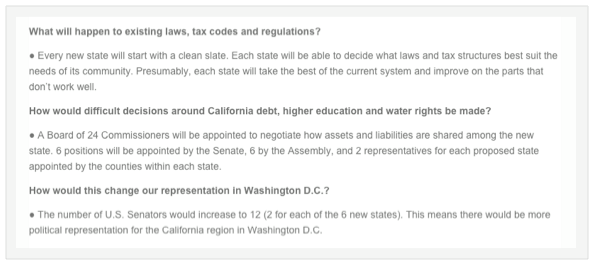

FAQs from the Six Californias’ website. No doubt, all 1.3 million signees thought about these questions before signing.

It’s a fairly safe assumption that 100% of the signature-gatherers would have to be “creative” in describing the initiative to disintegrate California. And as it turns it, there has been ample documentation of the very crafty ways petitioners have marketed the initiative to potential signatories.

One woman recounts being approached to sign a petition to increase the minimum wage, only to learn that it was actually to dissolve the state of California:

“Today while shopping I was approached by a signature gatherer who asked me whether I was registered to vote and would I like to raise the minimum wage. She had a sign at a small table in front of the store that said ‘Raise the minimum wage from $9.00 to $12.00 by 2016.’

I agreed and she handed me the clipboard, but as I started to read the measure she said ‘Oh that’s to split California into six states…’

She grabbed the clipboard back angrily and said ‘If you won’t sign this then they won’t pay me so you can just move along young lady.’”

Additionally, multiple people reported being asked to sign initiatives claiming to block the hare-brained scheme to split up California, only to find, upon examining the document, they’d be signing something that says the opposite!

“I was approached by a campaigner at Walmart who tried to get me to sign the petition…The canvasser said the petition was to oppose the division of California but I read it and said the proposal was in support of dividing California. … I told him to stuff it, but I bet a lot of people signed it thinking they were opposing, not supporting the division of California.”

Another Californian recounted being similarly misled:

“I read [the petition]… and I said to him, ‘you’re completely misrepresenting what these things are about.’ Then he proceeded to tell me I must not know how to read and understand these petitions correctly.”

When presented with the accusation of petitioners using fraudulent messages to market Six California, Michael Arno, the owner the the petition signature company hired by Draper, responded with incredulity:

“That’s the first I’ve heard of it… I have no idea why that would happen. This has been one of the cleaner drives I can remember…I can’t control all circulators, and I think it’s a very de minimis problem when you figure we collected 1.3 million signatures.”

Arno’s position — that a few bad apples misled people into signing the petition — is not a reasonable position that stands up to logic. Did 1.3 million people in California really know they were signing a petition to blow up the state? That all new states would have to rewrite all of their laws from scratch and figure out how to allocate debt and natural resources amongst themselves? Or more likely did most of them think they were signing something else entirely, like raising the minimum wage? Does anyone ever know what they’re signing when they quickly dash off their signature for any ballot initiative?

Conclusion

While presented as a product of grassroots action, California ballot initiatives are anything but. If you want to get an initiative on a ballot to change the state’s Constitution, you just need to pay a petition firm a few million bucks and it will happen. The petitioners will get people to sign the document by any means necessary, because they have the incentives to do so.

While it’s easy to pick on the signature-gathers for distorting the truth to get signatures, American politicians bend the truth more aggressively as a matter of company practice. Practically every political advertisement or speech selectively edits the truth to get your vote — this is just how it is in America. Should we really expect that freelance petition-gatherers be held to a higher standard than leaders of government?

The case of Six Californias is only notable because the petition collection firm, Arno Political Consultants, fucked up so monumentally. They had one job — to collect enough signatures — and they blew it.

This post was written by Rohin Dhar. Follow him on Twitter. To get occasional notifications when we write blog posts, sign up for our email list.