Every fall, over the span of 24 days, 3 million people flock to Dallas for the State Fair of Texas. And though these folks frequent the fairgrounds for many reasons (college football, auto shows, and carnival rides included), they spend the lion’s share of their money — some $38 million a year — on fried foods.

Texas has a long-winded love affair with foods of the deep-fried variety. Though this method of cooking was common in America as early as the 1890s, the trend didn’t really catch on until two Dallas brothers, Carl and Neil Fletcher, had the revelation of dipping a hot dog into cornmeal batter and frying it at the 1942 state fair. Their invention, the “Corny Dog,” was an instant hit, and endures to this day: some 500,000 are sold each year at the Texas fair alone.

Though equally legendary (and no doubt necessary) innovations joined the corn dog over the ensuing decades, deep-frying didn’t really take off on its own inventive, insane path until the Texas fair launched the “Big Tex Choice Awards” in 2005 — a contest rewarding the fair’s most inventive friers.

Since then, writes one food journalist, deep-frying has become an “extreme sport” in Texas.

And in this so-called “sport,” one Abel Gonzales Jr. is the Michael Jordan. In the frying contest’s nine years, Gonzales has won six times. His creations — fried coke, fried butter, and fried peanut butter and banana sandwiches — have earned him the title of “Fried Jesus” in his home state, and earn him enough money during the 24 day state fair that he was able to quit his full-time job as a database programmer.

But what drives a man like Gonzales to pursue the vast, greasy tundra of deep-fried foods?

Life in a Traditional Kitchen

Gonzales with old friends

Abel Gonzales Jr. was born into the food business.

As a child in the suburbs of Dallas, he spent his summers toiling in the kitchen of his father’s restaurant. One of the first “Tex-Mex” eateries ever opened in Texas, “A. J. Gonzales’ Mexican Oven” was a busy, stuffy, energetic establishment — one saturated with the aromas of enchiladas and flautas.

“Before I could even reach the sink, I was in there washing dishes,” recalls Gonzales, with a hearty chuckle. “Whenever I got in trouble as a kid, my father would send me back into the kitchen to scrub.”

Gradually, he moved into a role as a prep cook, then a “real cook,” a position that required constant mental acuity. Devoid of computer systems or tickets, the restaurant required Gonzales to remember every order by memory — sometimes, up to 15 at a time. By the time he was in his late teens, Gonzalez had grown disillusioned with cooking and preparing the same dishes over and over. “There was not a whole lot of creativity there,” he says. “I was taught to not deviate from the menu, and it became robotic.”

So, Gonzales left the wild world of cooking and, in the midst of the 90s tech boom, landed a warehouse job at a mail marketing company. For nearly a decade, he worked his way up the chain, and after self-teaching himself programming, settled into a role as a database analyst. He was making “good money,” had benefits, and was saving for retirement — but deep down, Gonzales felt something was still missing in his life.

“All these restrictions my dad had on me in his kitchen growing up, making me following the rules, just made me want to get out and break them,” says Gonzales.

As it turned out, his vessel for achieving this would be a deep fryer.

Trials and Tribulations of a Deep-Fry Cook

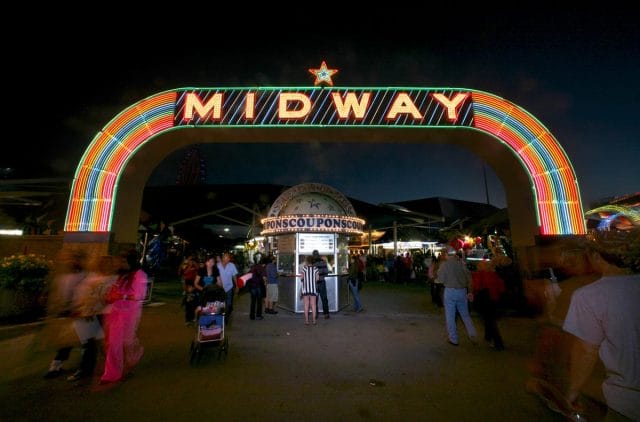

The State Fair of Texas

In his youth, Gonzales enjoyed few things more than the State Fair of Texas. “It was a huge event for us, it was like Christmas,” he says. “My mom would get my sisters and I new outfits and new shoes, and coordinate us.”

The best part, he recalls, was the carnival food — though it was predictable, and the same every year: “you knew what you were going to see there — corn dogs, cotton candy, turkey legs; there was never anything new.”

Years later, in the Fall of 1999, he was there with some programmer friends, and questioned the lack of experimentation in fair food. “I thought, why not just open my own booth? I can do this.”

But when the enthusiastic ex-cook looked into it, he realized this was a more challenging endeavor than he’d anticipated: there are some 200 food booths at the fair controlled by a long-time pack of 80 vendors — many of whom have held the spots for decades, or even generations.

Every year, only two or three new spots open up, and hundreds of applicants compete for them. Gonzales, who had limited resource, had to “work with what [he] had” to impress the vendor association:

“At my dad’s, we had our own sopapilla [a fried pastry] recipe. I cooked it, and had this guy make me a custom cookie cutter. So, I cut out these things in the shape of Texas, put them in the fryer, and topped them with whipped cream, honey, and strawberries.”

His idea was accepted. With an investment of “under $50,000,” he then procured all of the necessary equipment (including a deep fryer from Target), and set up shop.

Financially, the first year was a bit disappointing. “We didn’t make a whole lot of money; we broke even,” he says. “Eventually though, I learned how to get people to come to my booth, and how to hustle to get sales.”

For several years, Gonzales used his deep fryer to dream up “the next big carnival food hit” — he fried everything from meatballs to burritos — but nothing really caught on, and his business continued to struggle. At that point, the 24-day fair was really just his yearly vacation from his programming job, and an excuse to have fun and be around the place he loved most.

In 2005, Gonzales got his first “deep fried breakthrough.”

Gonzales’ deep-fried peanut butter and banana sandwich

That year, in an effort to foster innovation, the State Fair of Texas started the “Big Tex Awards,” which would dole out “Best Taste” and “Most Creative” honors to two vendors each year. Winning the award came with bragging rights, but also news coverage, publicity, and increased sales. The first year’s theme was “Elvis,” and Gonzales knew exactly what to do.

“I remembered that Elvis like his peanut butter and banana sandwiches,” he recalls. “I knew he grilled his, but I didn’t have a grill, so I fried them.”

When Gonzales’ deep fried sandwiches won for “Best Taste,” he sat back and waited for his business to explode — but it never happened. “Nobody was really ready for the whole weird items being deep-fried thing,” he says. “I sure as hell wasn’t.”

Gonzales realized that in order to really get attention, he’d have to make something not only delicious, but bat-shit crazy enough to turn heads. He tried frying jambalaya; he tried frying balls of meat; he even tried frying lettuce — all without viral success. Then, somewhat serendipitously, came the idea that changed his life.

Frying High

Deep-fried Coca-Cola

Late one night at the beginning of the 2006 state fair, Gonzales was in the back of his stand washing some cookware when he overheard a lingering customer talking to his friend at the counter. “What are you guys going to be crazy enough to try next?” asked the customer. “Fried Coca-Cola?”

“I thought, holy shit,” recalls Gonzales, “who wouldn’t want fried Coke?”

The following morning, before the crowds gathered, Gonzales bought a few cases of Coca-Cola and spent several hours dumping the liquid into the fryer. Soon, he settled on a concoction that worked: 830 calories worth of deep-fried Coca-Cola-flavored batter topped with Coca-Cola-flavored syrup, whipped cream, cinnamon, and, for those concerned about daily fruit intake, a cherry. Just one year after winning the “Best Taste” award, Gonzales won “Most Creative” — and this time, it paid off.

“It was a media circus — it was unreal,” he says. “I was asked to appear on The Today Show, Fox & Friends, I was on the news in Australia, and Argentina, and Japan…everyone wanted to talk about it.”

By the end of the 2006 fair, he’d sold more than 20,000 cups of fried Coca-Cola at $5 a cup. After paying the fair its 25% cut, and subtracting his overhead costs (supplies, ingredients, taxes, staff wages), he made away with a little more than $1 per cup, or $20,000 in total.

In 2007, Gonzales won “Best Taste” again, this time for his fried cookie dough; coupled with lingering press for his Coca-Cola creation, the invention doubled his sales. That fall, he made enough money to quit his day job as a programmer, and focus solely on his deep-frying endeavors. Though he had a feeling that his 15 minutes of fame were coming to a close, in reality, his best days were yet to come.

Gonzales’ stand, ‘Vandalay,’ gets insanely crowded

“When I like something, I eat it obsessively,” says Gonzales, “and 2009 was a toast and butter kind of year. I started thinking: how can I use this in the deep fryer?” His result, “deep-fried butter balls” (literally, balls of butter fried in a boiling vat of fat), debuted at the 2009 fair, and took the world by storm.

If Gonzales’ booth was popular before, now it was a madhouse: reporters stumbled over each other to interview him, crowds stood in 30-minute lines under the hot sun just to get a taste, and celebrity chefs like Rachael Ray and Andrew Zimmern touted his creation on their shows. Even Oprah flew out with her film crew (she later called Gonzales a “guru.”)

Gonzales didn’t just fry dough — he raked it in.

Gonzales’ fried butter balls

In a three week period, he consistently sold 10,000 orders on weekend days, and 5,000 to 7,000 orders per weekday. All told, he sold some 140,000 butter balls alone. “I lost count after 40,000 or so,” he says, “then I had to look back at how much butter I’d gone through.”

With his profits, Gonzales settled into a comfortable life. He bought out his parent’s old east Dallas home, and spent the 340 days per year outside of the fair “just lounging around,” watching TV, and playing with his dog.

“People think I’m really motivated, and that I’m working on stuff all the time, but the truth of the matter is that I’m a pretty lazy person,” he admits. “I don’t like to do a whole lot in the ‘off-season.’ I just sit on my ass all day long, sleep in late, and make fun of people who are working.”

Occasionally, he’ll be offered opportunities to fry for private parties or events, but for the most part, he declines. “It would be a big hassle to move all my gear over there,” he says, “and ultimately, it just isn’t worth it.”

Beauty Is in the Fry of the Beholder

Today, Gonzales continues to do well for himself at the State Fair of Texas each year, and considers himself “probably one of the only” professional deep-fryer out there. He’s well-liked, respected, and renowned for his willingness to fry just about anything.

“I have people coming up, asking me to fry their wallets, their sandals, their unruly kids,” he jokes. “One guy came up and said, ‘Here’s $100, can you put that in the batter and see what it comes out like?’ The request are endless.”

The requests also speak to the general population’s misguided belief that frying is easy. “They think you can put anything in the frier and it will be a hit,” he adds, “and that’s just not true.” Deep-frying, says Gonzales, is an art form — one requiring the right mixture of timing, creativity, and know-how:

“Anybody can dump something in a fryer. But there is a skill involved. Like, if you want to fry a watermelon piece, and you just put it in, it won’t hold its shape. You’re going to have to protect it, or coat it with something, and you’re going to have to refrigerate it when it comes out of the fryer. Then there’s the rising agent — cornstarch, or baking powder, or cornmeal with flour. There’s a whole process you have to learn.”

For this reason, Gonzales considers himself a pioneer who straddles the divide between inventor and chef.

“Never, never, never did I think this was going to be my future,” he laughs. “As much as I loved the fair, and dreamed about it as a kid, if you were to say I was going to end up one of those guys at the fair, I would have thought you were crazy. But, here I am.”

This post was written by Zachary Crockett. You can follow him on Twitter here.

To get occasional notifications when we write blog posts, please sign up for our email list.