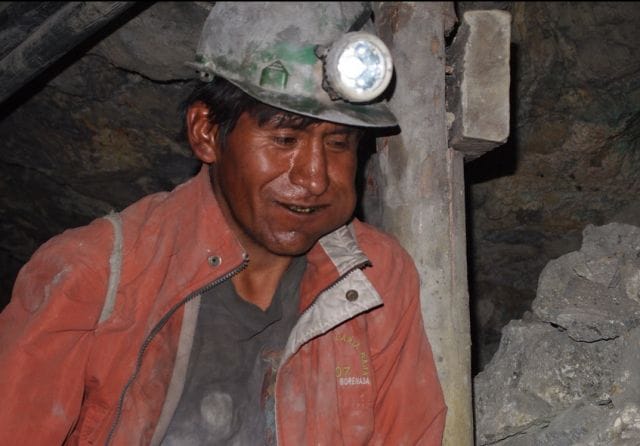

Tin miner in Potosí, Bolivia; Zachary Crockett

Adelmo rises at 3:30 am, stuffs a wad of coca leaves in his cheek, and descends into the bowels of the earth. His rubber galoshes tweet through the tunnel’s chamber like desperate sparrows; the shadows cast from his three-pound headlight bob along the jagged walls until they fade into a void of darkness.

He’s 29, and likely has about ten years left to live; the vast majority of Bolivians with his job succumb to silicosis or lung cancer in their mid-40s. He’ll spend the next eight hours jackhammering into hard stone 400 feet underground with no guaranteed payoff at the end of the day. After a good 12-hour shift, he’ll leave with the equivalent of US $15; on a bad day, he’ll dislodge a boulder and get himself killed — it happens at least twice a week to miners in Potosí’s Cerro Rico, “the rich hill.”

Since mining first began in Bolivia nearly 450 years ago, conditions haven’t changed much for workers, but Adelmo’s city has seen the highest highs and lowest lows: once the richest city in the Americas, Potosí is now one of the poorest.

The City Made of SIlver

According to one scholar, Potosí “shaped history, changed nations and helped create empires.” But before it did any of this, it was a quaint region, inhabited by peaceful Charcas and Chullpas natives who were artisans and potters. The city — the “highest in the world,” at 13,343 feet — was first exploited by the Incas, who colonized the area and began mining the for silver in the city’s surrounding hills during the early 1500s. This brought them great wealth — enough to pay the ransom for their emperor when the Spanish invaded in 1539.

At first, the Spanish weren’t aware of the riches beneath their feet. Legend has it, a native named Diego Huallpa was herding llamas when he pulled out a root in the ground and found a vein of silver; word spread, and soon the Spanish had set up their first mine in Potosí, La Descubridora, “the discoverer.” The wealth of silver that was excavated was like nothing they’d ever seen.

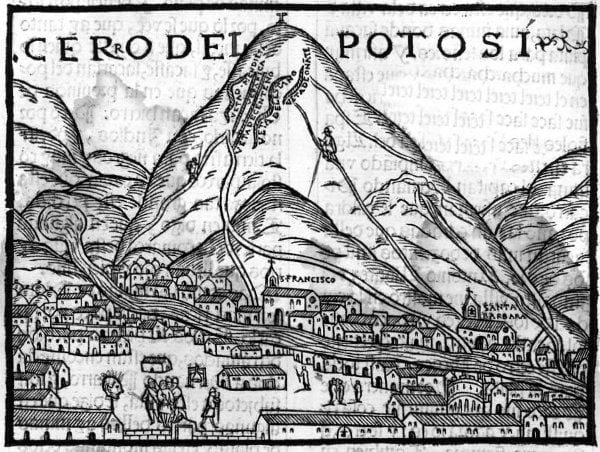

Source: debitage

The silver was so vast that in 1553, Charles the 5th, the King of Spain, presented Potosí with a coat of arms and declared it “the imperial village.” In popular culture, the city became a legend and the Americas’ paradigm of immense wealth: the phrase “vale un Potosí” (it’s worth a Potosí) was commonly used to describe luxurious possessions.

The Spanish enslaved indigenous populations and forced them into the mines, where they worked 12-hour shifts for months on end. During this time, the colonists also introduced mercury as a way to purify the mineral in it’s raw form; silicosis pneumonia, mercury poisoning, and atrocious work conditions cost so many miners their lives that the Spanish began importing slaves from Africa.

Within a few decades, Potosí’s population had swelled to over 200,000; it had become one of the world’s richest cities, and one of it’s biggest. But the Spanish were more interested in mining than establishing a functioning city: Potosí was in “urban chaos,” with huts haphazardly sprawled through the valley. The city and the mines were tantamount: those who didn’t mine provided goods and services to those who did.

By the 1570s, a Spanish mint was opened to process coins for the empire; when this become too small, another was built in 1751 that was “15,000 square feet and had over 200 rooms.” By this time, Potosí had gained a reputation for its ostentatiousness; the streets were paved with enough silver to build a 5,000-mile bridge to Madrid, Spain.

But as the hen that lays the silver egg, Potosí was constantly subjected to territorial dispute. In 1810, a fifteen year war ensued; by 1835, the Bolivians had won independence from Spain, but at a great expense. From 1545 to 1825, 8 million miners died.

When Silver Turns to Non-Precious Metals

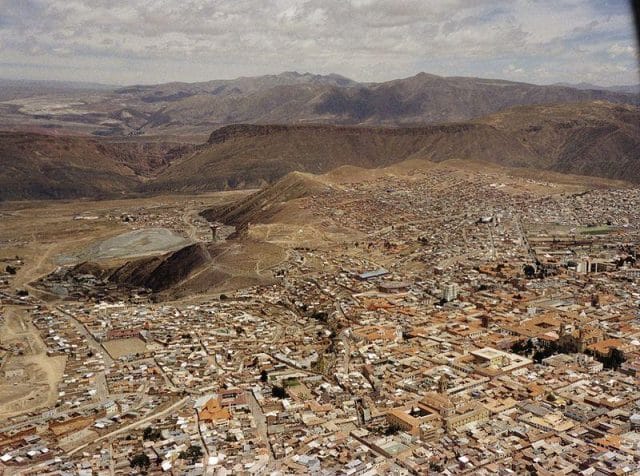

Source: Forkingitup

Potosí was in ruins: once ornate and flowing with riches, it was now ransacked, looted, and desolate; the mines had practically run dry of silver, and the industry was crippled. In less than twenty years, the city’s population dwindled from 200,000 to 9,000, and its economy collapsed.

In 1850, Potosí saw a brief revival in mining when there arose an international need for tin, but in 1879 Bolivia was embroiled in another conflict, The War of the Pacific — this time with neighboring Chile. In the process, they lost an incredibly valuable asset: their access to the sea. All tin exports now had to be exported through foreign ports, and faced steeper taxes. At the same time, tin prices plummeted, and extraction and purification methods became more expensive as the metals became scarcer. Potosí’s economy tanked again.

Corporación Minera de Bolivia (COMIBOL), created in 1952, was the first massive movement toward organized labor for Bolivian miners. Yet COMIBOL took fifteen years to bring tin production back to pre-revolutionary levels. They made poor investments in mining technology, continued to lose money, and had to cut pay-rolled miners from 27,000 to 7,000 in less than one year.

A 14 year old miner prepares to hoist up a 200 pound mineral load

Tin prices crashed again in 1985 and 15 years of neoliberal restructuring ensued in Bolivia; capital increasingly vanished the the impoverished departments of Potosí. Subsequently, all COMIBOL-owned mines were shut down to examine economic feasibility; many never reopened. Potosí’s largest mine, San Cristóbal (which produced 1,300 metric tons of zinc-silver ore and 300 tons of lead-silver ore per day) was sold off to a Japanese company.

The industry has stayed alive today, but clings to life by threads. Mostly non-precious metals are mined — zinc, antimony, lead, cadmium — for minimal profit. Potosí is a shadow of what is once was. Once littered with silver and decadence, Potosí is now desolate, crumbling, fatigued.

The miner’s life is as tough as it gets here: 12-hour shifts, continuously brutal work for three months at a time with no days off. Boys as young as nine years old join their fathers in the mines and learn the ropes; the city’s education system is an utter mess. For miners, average pay wavers around 2,000 bolivianos per month (US$334 — or $83 per week); Potosí is so impoverished, this actually has considerable buying power there, but as the saying goes in the city, “el minero gana bien, pero vive corto” — miners earn a good living, but live shortly.

Deep below the earth’s surface, the air is thin, temperatures fluctuate from brutally cold to blisteringly hot, and tiny tunnels relegate miners to a squatted crawl for hundreds of meters at a time. Safety precautions are sparse, and labor conditions are medieval — no shafts or advanced technology: everything is done with antiquated metal tools and old, crusty machinery.

There remains a small glimmer of hope for the city’s economy in tourism, but even that industry seems doomed for Potosí. Geologists recently discovered that years of mismanaged mining abuse have caused a giant sinkhole to form under Cerro Rico, Potosí’s defining peak. Should the peak collapse, it would complete the full lapse from riches to dust. Marco Antonio Pumari, vice president of Potosí’s civic committee, mourns his city’s continued hardships:

“The people of Potosí don’t have industries, we don’t have businesses that generate employment. If the Cerro is lost, if it sinks, what tourist is going to come here? Will they come to see that here there was a mountain that maintained the whole world?”

But for miners like Adelmo, there is no respite; tomorrow, he’ll be back in the sulfurous depths of the “rich hill,” carving out the stones of his livelihood.

This post was written by Zachary Crockett. Follow him on Twitter here, or Google Plus here.