“I didn’t really even think to ask [for permission to use the images]. I don’t think that way. It didn’t occur to me to ask him and even if I did and he said ‘no’, I still would have taken them.”

~ Artist Richard Prince, on photographing images by another photographer, then selling them for millions of dollars

![]()

In early 2014, renowned painter and photographer Richard Prince picked up his iPhone and began scrolling through other people’s photos on Instagram.

When the 66-year-old would find a picture to his liking — usually a selfie taken by a young, scantily-clad female — he’d leave a comment (something like, “Don’t du anything. Just B Urself © ®”) then save a screenshot to his phone. Eventually, the artist hand-picked 37 of these screenshots, ink jetted them, unmodified, onto 6-by-4 foot canvases, and titled the series “New Portraits.”

Several months later, Prince’s collection of others’ Instagram photos adorned the pristine, white walls of a Madison Avenue art gallery. On opening night, art critics and New York socialites debated the complexities of contemporary art between toasts of expensive champagne. The images went on to sell at auction for $90,000 a piece.

For Prince, this maneuver was nothing new: the artist has spent the better part of four decades taking photographs of other people’s photographs without permission, then selling his version, sometimes for millions of dollars. In the past 15 years alone, auction records show more than $300 million in sales of Richard Prince works — the vast majority of which are either “re-photographs” or adaptations of pre-existing photographs. He is routinely denounced as a thief, a marauder, and a “cheap hack”, yet he has become, far and away, the world’s highest-grossing “photographer”.

But Prince’s artwork raises several interesting questions: How is what he’s doing legal? Where is the line drawn between art and plagiarism? And ultimately, what does his work say about the changing nature of authorship on the Internet?

A (Very) Brief History of Appropriation Art

Marcel Duchamp’s “Fountain” (1917)

In the art world, appropriation is defined as “the use of pre-existing objects or images with little or no transformation.” By doing so, the artist intends to recontextualize the borrowed material in a new light.

Though Pablo Picasso dabbled in appropriation more than a century ago (notably, by using actual newspaper clippings in his 1913 work, “Guitar, Newspaper, Glass and Bottle”), most art historians attribute the technique’s origin to French conceptual artist Marcel Duchamp. Art, in Duchamp’s view, was achieved not through original creation, but “the process of selection and presentation.” In 1917, the artist simply procured an old urinal, signed it with a pseudonym, and named it “Fountain.” While his intention was to “pose a direct challenge to traditional perceptions of fine art, ownership, originality and plagiarism,” critics unanimously rejected the piece from exhibits and discredited it as a serious artwork.

Around the same time, a larger movement sprouted in Europe. Dadaism, which championed itself as a form of “artistic anarchy [against] the values of the time,” heavily endorsed the use of appropriation in art. These ideas were adopted by subsequent generations, and later became intertwined in the “pop art” movement of the 1960s. Artists like Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein removed original material from its context and recontextualized it to comment on issues like consumerism and women’s rights.

Roy Lichtenstein’s “Drowning Girl” (1963) is appropriated from a strip in DC Comics’ Secret Hearts #83, and recontextualized to make a commentary about women’s liberation

Andy Warhol’s “Campbell’s Soup Cans” (1962) enlisted a highly recognizable image to comment on the kitschy elements of advertising, and the mechanical nature of mass production

In 1967, French theorist Roland Barthes published “The Death of the Author”, an essay challenging the preconceived notions of authorship. Any “new” work, contended Barthes, “is a tissue of citations, resulting from the thousand sources of culture”; since the author is merely borrowing from preconceived ideas, he is irrelevant.

Barthes’ thoughts sparked a new wave of appropriation art, in which authorship and copyright were deemed to be immaterial — and Richard Prince was right in the thick of it.

The Reckless Rise of Richard Prince

Born on August 6, 1949, in the U.S.-controlled Panama Canal Zone, Richard Prince eventually found his way to Maine, where he attended Nasson College. Here, he became deeply interested in the art world, and decided he’d try to cut it in New York City. Once there, he struggled to make ends meet, working “countless shitty jobs” in the service industry.

By 1973, he’d landed a job at Time, Inc., providing tear sheets (pages torn from magazines) to clients as proof that their advertisements had been published. His desk was perennially covered with stacks of these advertisements — and for the hell of it, he decided to re-photograph a few of them and “present them as [his] original work.” He likened this method to “beachcombing”: he’d find an image of a model or a piece of jewelry, then, with no regard for the original photographer, snap a shot of it and present it out of the context on the original ad.

“At first it was pretty reckless — plagiarizing someone else’s photograph, making a new picture effortlessly,” he later said. “Making the exposure, looking through the lens, and clicking, felt like an unwelling… a whole new history without the old one.”

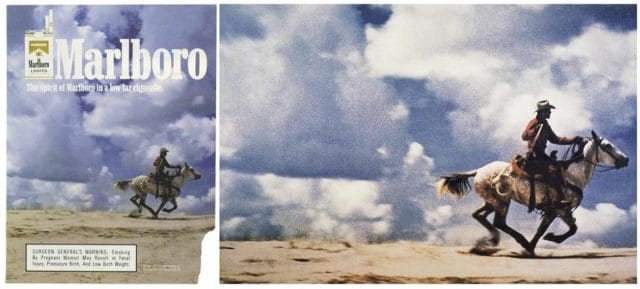

For his first series, “Cowboys”, he rounded up Marlboro cigarette ads and photographed the cowboys in the images, cropping out everything that associated it with the brand.

One of Prince’s “Cowboys” (right), with the original source it was taken from; this artwork sold for $1.2 million

“Every week, I’d see one and be like, ‘Oh that’s mine, Thank you,’” he recalled in an interview. “I had no skills [with] the camera. I used a cheap commercial lab to blow up the pictures. I made editions of two. I never went into a darkroom.”

He followed this series with “Gangs”, a collection of re-photographs of “biker chick girlfriends.” His stated purpose early on was to hone in on “social science fiction” — “the hyperreal space depicted in countless advertisements featuring gleaming luxury goods and robotic models.”

A re-photograph from Richard Prince’s “Girlfriends” (the original image was taken from a magazine)

But none of this really caught on in the art world, and critics discredited his methods as lazy. For the next decade, Prince more or less toiled through the poverty that comes with the pursuit of artistry: he lived in a series of tiny apartments by the railroad tracks, barely scraping by. Around 1986, out of desperation, he tried something new:

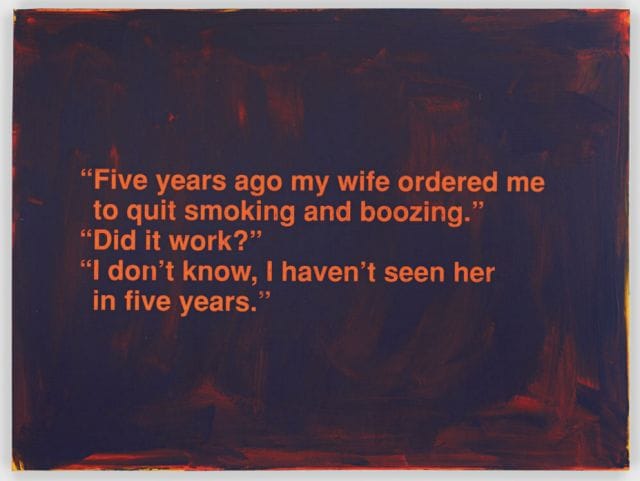

“I’d hit rock bottom. I’d been working 10 years and I still wasn’t known. So I wrote a joke in pencil on a piece of paper, and I’d invite people over and ask them, ‘Will you give me $10 for this?’ I knew I was onto something — if someone else had done it I would have been jealous. You couldn’t speculate about it. So much of art depends on the critic as the umpire. With a joke there’s nothing to interpret.”

Literally unoriginal jokes written (or, in some cases, painted) on pieces of paper or a canvas, Prince’s “Jokes” eventually gained steam and, with the help of some well-connected friends, Prince began to build a name for himself. By the late 1980s, he’d become a star in the contemporary art scene — and his appropriated photographs (Cowboys, Gangs) began selling like hot cakes.

“When they first came out, you couldn’t give them away,” he later joked in an interview with New York Magazine. “[Now] they’ve become pretty serious to people, which is funny…They’re just paint, stretchers, and canvas.” (In 2014, one of these sold for more than $3 million at auction.)

Prince’s true source of income though, has been a series of paintings of nurses he released in 2003. For these, he poured through thousands of erotica novels, plucked out those with nurses on the cover, then transferred these covers onto a canvas and slathered them with paint. The original artists have never been credited.

One of Richard Prince’s “Joke” paintings (Untitled – Five Years Ago My Wife); Richard Prince, 1998

Today, Prince is one of America’s most recognizable contemporary artists. He is also among its wealthiest.

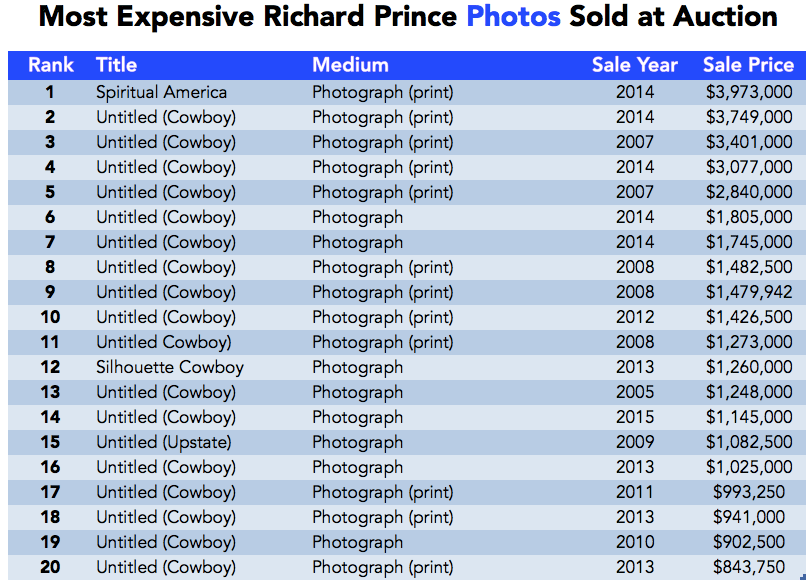

We analyzed Artsy, a site that collects historical auction data, and found more than 1,000 Richard Prince sales between 1998 and 2015. In total, his works have brought in $303,600,000 at auction — $73 million in re-photographs, and another $230 million in appropriated paintings. An astonishing seventy-five of these have sold for over $1 million a piece. His “Spiritual America” — a photo of a photo (taken by somebody else) of a nude 10 year-old Brooke Shields — commanded a whopping $3.97 million dollars in 2014.

“[Prince’s photos] are sexy, and mentally appealing to many collectors,” says Amy Cappellazzo, former co-head of contemporary art at Christie’s. “They always sell well.”

According to art analysis firm Artnet, Prince is one of the top 10 highest-grossing artists alive today — and he’s the only photographer on the list. With his earnings, he has purchased two $15 million dollar townhouses in New York City, as well as an 88-acre estate upstate.

Prince has achieved the success all artists dream of — but how is what he does legal? Most of us can’t go around photographing other people’s work, stamping our own name on it, and selling it for profit. So how exactly does Prince circumvent copyright law?

How to Legally Steal Other Artists’ Work

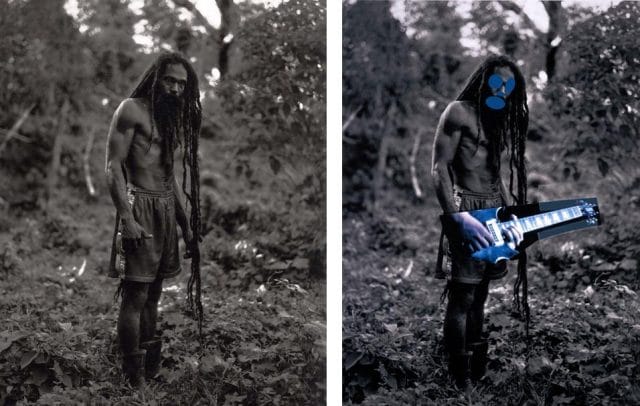

One of Cariou’s “Yes Rasta” images (left), and Prince’s modified version (right)

In 2000, a photographer named Patrick Cariou published Yes Rasta, a collection of black and white images he’d taken of Rastafarians in Jamaica. For Cariou, the book was the culmination of six years of hard work and dedication to his craft.

Eight years later, Richard Prince came across Yes Rasta in a bookstore and loved the images so much that he decide to photograph Cariou’s photos, slightly modify them, and call them his own. When Prince released the resulting series, “Canal Zone”, a who’s-who of A-list celebrities — Beyonce & Jay Z, Tom Brady, Robert DeNiro, Angelina Jolie, and Brad Pitt — attended the event, and he ended up selling eight of the photos for a total of $10,480,000. Carious himself never saw a penny of this, and wasn’t even aware that Prince had appropriated his original work.

“I didn’t really even think to ask [for permission to use the images],” Prince later stated. “I don’t think that way. It didn’t occur to me to ask him and even if I did and he said ‘no’, I still would have taken them. I figured I’d do them and maybe if he objected I’d deal with that later.”

When Cariou found out, he immediately sued Prince for copyright infringement.

At first, the court ruled in favor of Cariou, determining that Richard Prince had, in fact, infringed on his copyright of the photographs. But Prince and his lawyer appealed, and the second time around, Cariou was not so lucky.

The case of Cariou v. Prince became highly contentious: while people in the contemporary art world favored Prince’s stance, photographers endorsed Cariou. Ultimately, in 2013, the Second Circuit made its ruling: Prince’s appropriation was “transformative” enough to qualify for fair use. In the words of the presiding judge: “[Prince’s] work adds new meaning…and the fair use doctrine guarantees [him] breathing space.”

The majority of copyright claims on the 22 images were dismissed, and Prince settled with Cariou outside of the court, heavily in his own favor.

“Copyright has never interested me,” Prince has said of the case. “For most of my life I owned half a stereo so there was no point in suing me, but that’s changed now and it’s interesting.”

Richard Prince’s “New Portraits” series (Instagram photos taken from other users) at the Gagosian gallery in New York

The results of Cariou v. Prince help explain why Prince is able to get away with photographing other photographers’ work and selling it: by presenting old images in a new light, he supposedly adds meaning and value. This qualifies his work as “fair use”, and he can essentially bypass the confines of U.S. copyright law.

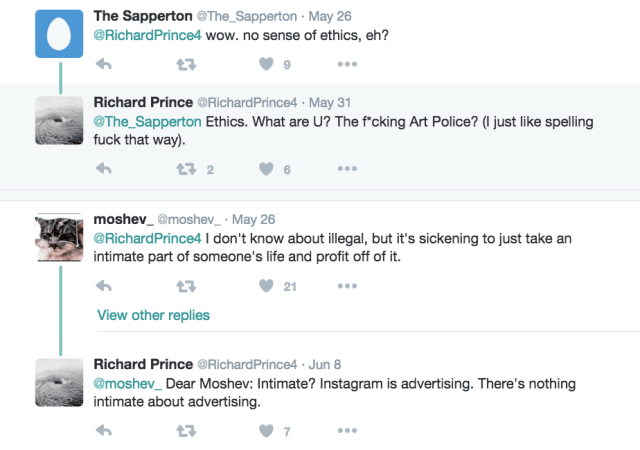

This is precisely why he was also able to screenshot random Instagram users’ photos, blow them up, and sell them at a gallery for tens of thousands of dollars: he added a comment to each photo before printing it, and this constituted as his “transformative” contribution. As one Instagram spokesman told The Washington Post, plagiarism of images is strictly disallowed within the platform — but outside of it, the company is powerless:

“People in the Instagram community own their photos, period. On the platform, if someone feels that their copyright has been violated, they can report it to us and we will take appropriate action. Off the platform, content owners can enforce their legal rights.”

So far, none of the women Prince stole images from have sued him — but one of them, a user by the name of “Missy Suicide”, has done something even better: she’s begun selling (wait for it) photos of Prince’s photo of her original photo. While Prince’s version sold for $90,000, she offers hers for a mere $90; all proceeds have been donated to the Electronic Frontier Foundation, a nonprofit that fights to preserve digital content rights.

“Do we have Mr. Prince’s permission to sell these prints?” she quipped on Twitter. “We have the same permission from him that he had from us. ;)”

The Modern Artist

Richard Prince jousts with a Twitter critic over the integrity of his Instagram series

Ultimately, while the ethics of Richard Prince’s artwork — and appropriation art in general — are debatable, his methods are familiar and relevant: He copies. He pastes. He takes without asking.

In many ways, he is the contemporary art world’s incarnation of the famous Steve Jobs quote, “Good artists copy; great artists steal.” But moreover, he’s a reflection of the digital age, in which texts and images can be separated from their original sources, get twisted and reshaped, and then reach a few hundred million people in the course of a day. In a world of remixes and memes, authorship is becoming less and less relevant: it doesn’t particularly matter where something originates on the Internet.

Richard Prince has seized on this dynamic to profit handsomely. Richard Prince, who takes photographs of photographs, is the richest photographer in the world.

![]()

Our next post charts the rise of Bayesian statistics. To get notified when we post it → join our email list.

![]()

This post was written by Zachary Crockett. You can follow him on Twitter at @zzcrockett